The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has traditionally rooted the legitimacy of its autocratic rule in the principle of institutionalization: it is the Party, and not a particular person or family, which holds the reins of power for, ostensibly, the benefit of all 1.4 billion Chinese.

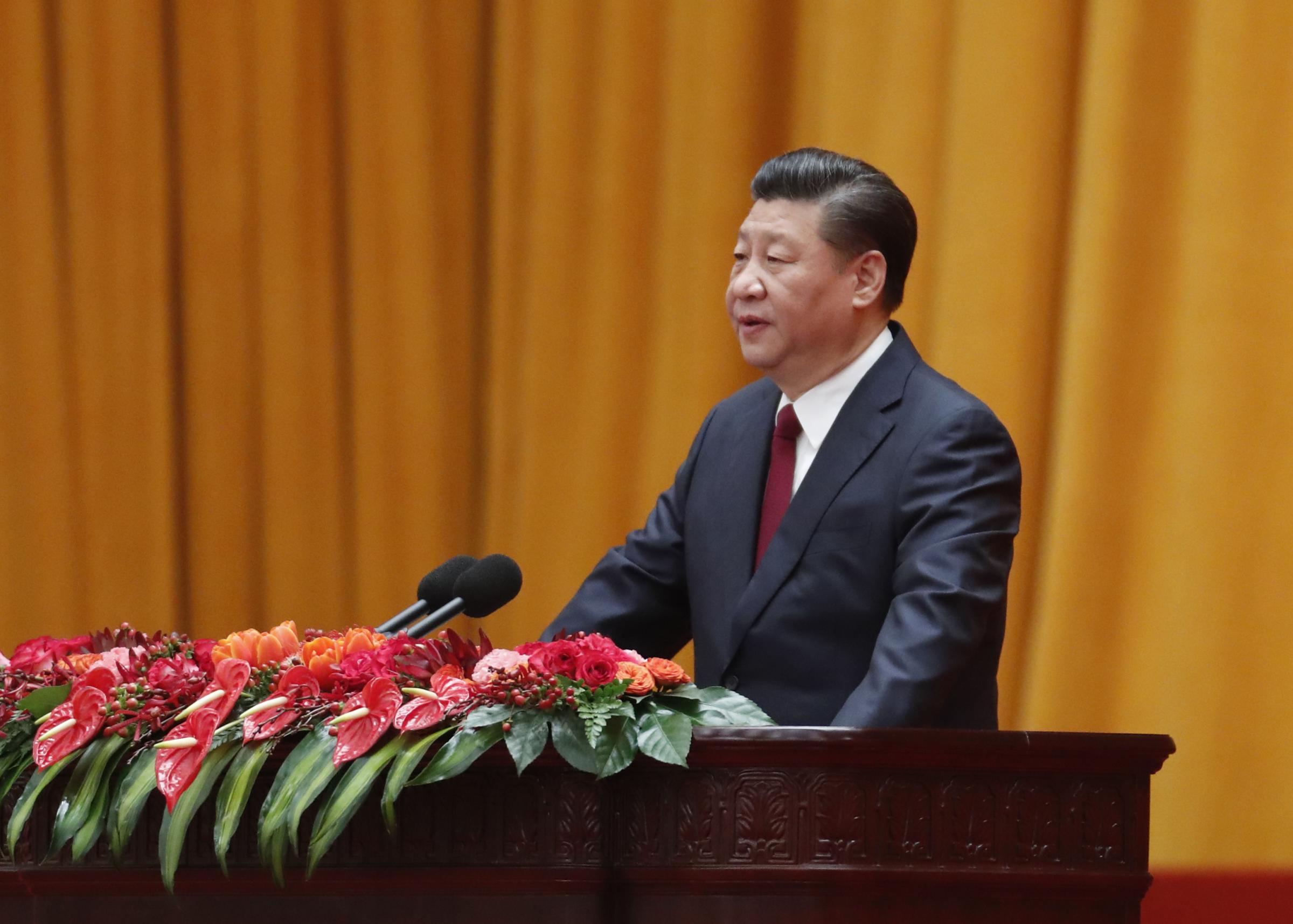

But that already specious assertion took a severe knock on Sunday following the publishing of a proposal — one certain to be ratified next month — that China’s two five-year presidential term limit be abolished. This will essentially allow current President Xi Jinping, who is already China’s strongest leader for generations, to remain in power for as long as he desires.

The move is the culmination of a series of power plays by Xi over recent months, including having his eponymous political thought enshrined in the national constitution, and failing to appoint any potential successors to China’s apex executive body, the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC). But the timing of the announcement before Xi has even officially completed his first term in office has stunned China-watchers and raised serious questions concerning the governance of the world’s number two economy going forward.

“This is a very significant move towards China transforming into a one-man system,” says Jude Blanchette, a Beijing-based researcher on Chinese politics for The Conference Board analysis firm. “It’s hard to overemphasize what a big deal this is for the future of China and the world given China’s importance to the global economy and global institutions.”

Xi’s consolidation of power domestically comes as he has also announced his intention to be more assertive internationally. His signature Belt and Road Initiative — a trade and infrastructure network tracing the ancient Silk Road though Eurasia and Africa — stands to radically boost China’s geopolitical clout at a time when the White House under Donald Trump has questioned key alliances and the very international institutions that have been the foundation of American hegemony.

Read More: Xi Jinping Becomes China’s Most Powerful Leader Since Mao Zedong

China’s burgeoning influence, augmented by Washington’s retreat into nativist languor, further normalizes autocratic political systems that have been on the rise since the 2008 financial crisis. Beijing has ramped up censorship and clamped down on dissent since Xi, 64, took power in late 2012, coupled with incessant trolling of Western democracy as unstable, unpredictable and unable to deliver the goods. Meanwhile, Trump has launched a war on the American media and toadied up to strongmen from Russia’s Vladimir Putin to Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte and, of course, Xi himself.

The question remains whether China is set to repeat past mistakes where unquestioning observance to its leadership contributed to disasters like the Great Leap Forward of the 1950s and Cultural Revolution a decade later. Academics and officials are increasingly reluctant to voice opinions that differ from the Party leadership, which is invariably hailed with gilded paeans in the state press, while critics are summarily detained.

“There’s a risk of it become courtier culture, sycophancy, just telling him what he wants to hear,” says Professor Nick Bisley, an Asia expert at Australia’s La Trobe University. “It doesn’t have to be like that but the risks are very real and unsettling for those inside and outside China.”

Agrees Blanchette: “If we hold that good policy outcomes require the maximum amount of voices and input in design and implementation then we should be worried.”

Xi should know the risks better than anyone. Like millions of his contemporaries, he was sent down to live in the countryside during the Cultural Revolution of the mid 1960s, reduced to toiling in fields and sleeping in a flea-infested cave in China’s hardscrabble central province of Shaanxi. His father was repeatedly purged by CCP patriarch Mao Zedong, whose unassailable cult of personality wreaked numerous hardships on his people, including the Great Leap Forward, a frenzied experiment in collectivized industrialization that cost some 20-50 million lives between 1958 and 1962.

It was because of these calamities that the CCP leadership from Deng Xiaoping — architect of China’s economic revival — introduced collective leadership around the PSC, presidential term limits to ensure a smooth leadership transition, and thus countering a Mao-like strongman ever holding the country to ransom again. But Xi over recent months has taken careful aim at each of these safeguards. Meanwhile, his trademark ideology of the “Chinese Dream” and “great revival of the Chinese nation” has drawn uneasy comparisons with Mao-era sloganeering.

“While there appears little internal opposition to Xi at present, it could emerge in the future, such as in the event of economic instability or a mishandled international incident,” says Tom Rafferty, regional manager for China at The Economist Intelligence Unit. “Nervousness about his position could lead Xi to back wider crackdowns and political purges.”

The lack of neither elections nor term limits risks such problems returning with a vengeance. And worryingly for the international community, that Xi is brazenly prepared to rewrite four decades of political orthodoxy at home means he would have few qualms about tearing up the rulebook abroad, where Beijing has long flouted international norms that it perceives as constraining its interests.

“It’s another piece of evidence that says be worried about a China led by Xi Jinping,” says Bisley. “Because if he’s happy to do this at home, then boy is he going to be happy to do it abroad.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Charlie Campbell / Beijing at charlie.campbell@time.com