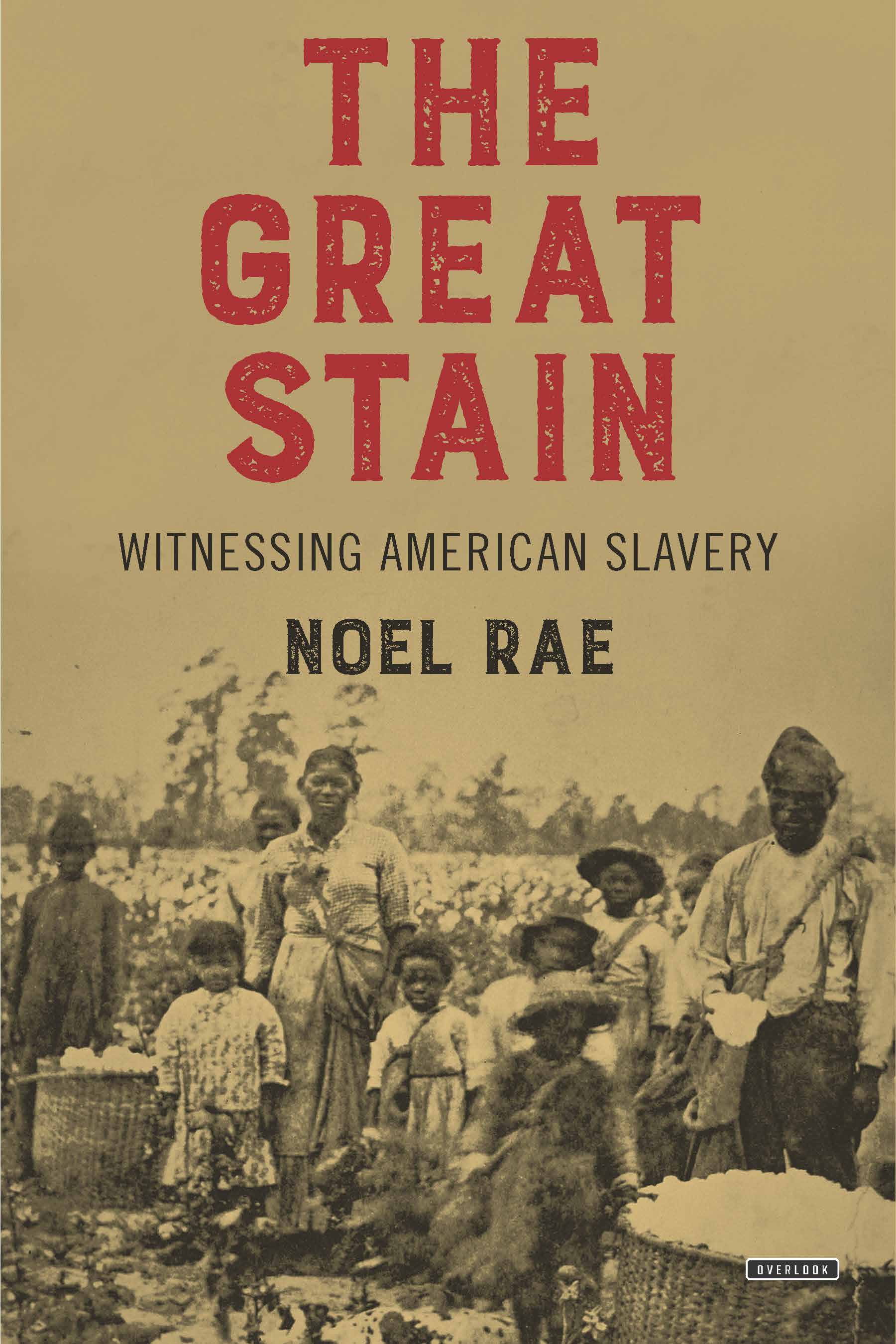

During the period of American slavery, how did slaveholders manage to balance their religious beliefs with the cruel facts of the “peculiar institution“? As shown by the following passages — adapted from Noel Rae’s new book The Great Stain, which uses firsthand accounts to tell the story of slavery in America — for some of them that rationalization was right there in the Bible.

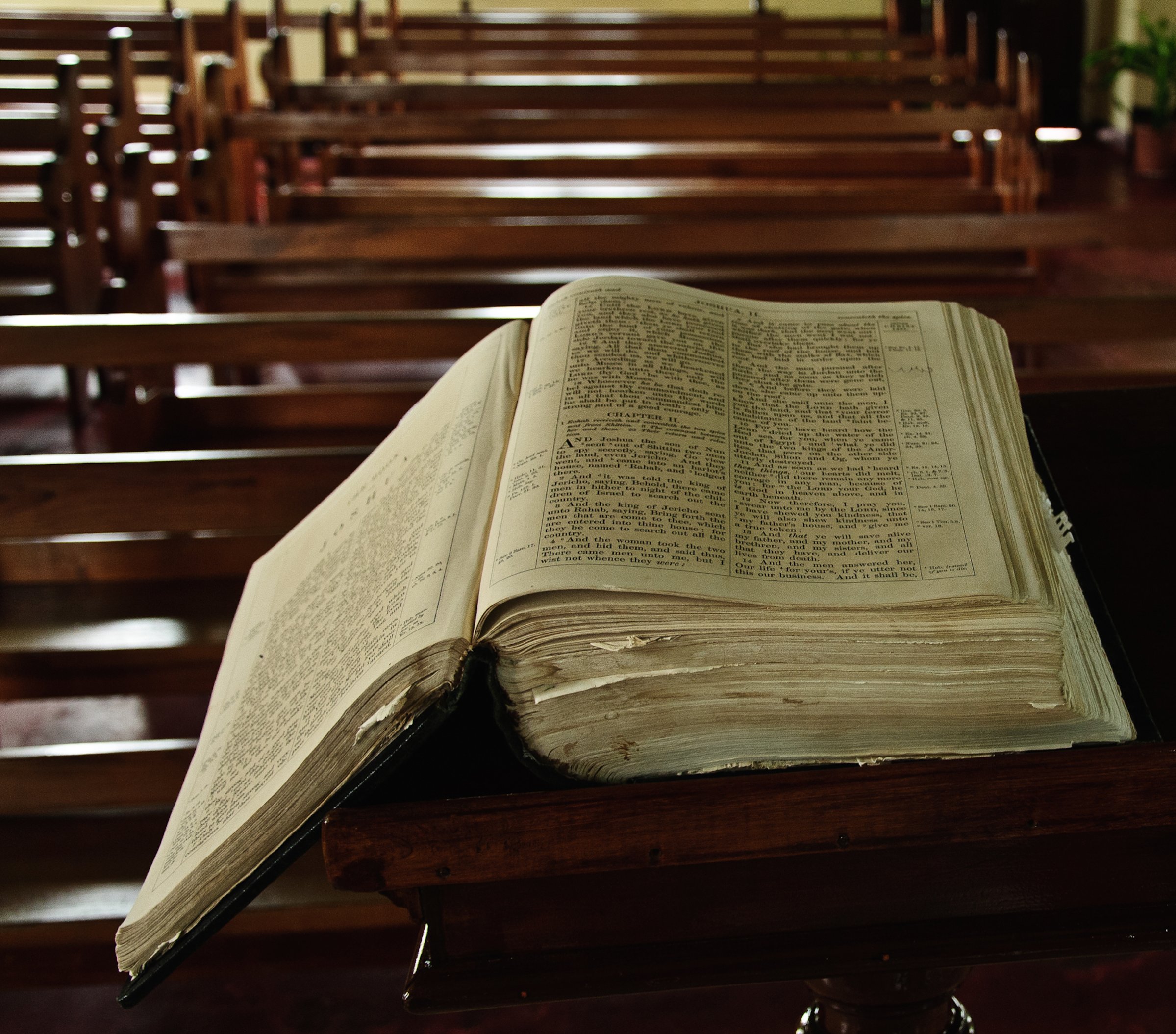

Out of the more than three quarters of a million words in the Bible, Christian slaveholders—and, if asked, most slaveholders would have defined themselves as Christian—had two favorites texts, one from the beginning of the Old Testament and the other from the end of the New Testament. In the words of the King James Bible, which was the version then current, these were, first, Genesis IX, 18–27:

“And the sons of Noah that went forth from the ark were Shem, Ham, and Japheth: and Ham is the father of Canaan. These are the three sons of Noah: and of them was the whole world overspread. And Noah began to be an husbandman, and he planted a vineyard: and he drank of the wine, and was drunken; and he was uncovered within his tent. And Ham, the father of Canaan, saw the nakedness of his father, and told his two brethren without. And Shem and Japheth took a garment, and laid it upon both their shoulders, and went backward, and covered the nakedness of their father; and their faces were backward, and they saw not their father’s nakedness. And Noah awoke from his wine, and knew what his younger son had done unto him. And he said, Cursed be Canaan; a servant of servants shall he be unto his brethren. And he said, Blessed be the Lord God of Shem; and Canaan shall be his servant. God shall enlarge Japheth, and he shall dwell in the tents of Shem; and Canaan shall be his servant. And Noah lived after the flood three hundred and fifty years.”

Despite some problems with this story—What was so terrible about seeing Noah drunk? Why curse Canaan rather than Ham? How long was the servitude to last? Surely Ham would have been the same color as his brothers?—it eventually became the foundational text for those who wanted to justify slavery on Biblical grounds. In its boiled-down, popular version, known as “The Curse of Ham,” Canaan was dropped from the story, Ham was made black, and his descendants were made Africans.

The other favorite came from the Apostle Paul’s Epistle to the Ephesians, VI, 5-7: “Servants, be obedient to them that are your masters according to the flesh, with fear and trembling, in singleness of your heart, as unto Christ; not with eye-service, as men-pleasers; but as the servants of Christ, doing the will of God from the heart; with good will doing service, as to the Lord, and not to men: knowing that whatsoever good thing any man doeth, the same shall he receive of the Lord, whether he be bond or free.” (Paul repeated himself, almost word for word, in the third chapter of his Epistle to the Colossians.)

The rest of the Old Testament was often mined by pro-slavery polemicists for examples proving that slavery was common among the Israelites. The New Testament was largely ignored, except in the negative sense of pointing out that nowhere did Jesus condemn slavery, although the story of Philemon, the runaway who St. Paul returned to his master, was often quoted. It was also generally accepted that the Latin word servus, usually translated as servant, really meant slave.

***

Even apparent abuses, when looked at in the right light, worked out for the best, in the words of Bishop William Meade of Virginia. Suppose, for example, that you have been punished for something you did not do, “is it not possible you may have done some other bad thing which was never discovered and that Almighty God, who saw you doing it, would not let you escape without punishment one time or another? And ought you not in such a case to give glory to Him, and be thankful that He would rather punish you in this life for your wickedness than destroy your souls for it in the next life? But suppose that even this was not the case—a case hardly to be imagined—and that you have by no means, known or unknown, deserved the correction you suffered; there is this great comfort in it, that if you bear it patiently, and leave your cause in the hands of God, He will reward you for it in heaven, and the punishment you suffer unjustly here shall turn to your exceeding great glory hereafter.”

Bishop Stephen Elliott, of Georgia, also knew how to look on the bright side. Critics of slavery should “consider whether, by their interference with this institution, they may not be checking and impeding a work which is manifestly Providential. For nearly a hundred years the English and American Churches have been striving to civilize and Christianize Western Africa, and with what result? Around Sierra Leone, and in the neighborhood of Cape Palmas, a few natives have been made Christians, and some nations have been partially civilized; but what a small number in comparison with the thousands, nay, I may say millions, who have learned the way to Heaven and who have been made to know their Savior through the means of African slavery! At this very moment there are from three to four millions of Africans, educating for earth and for Heaven in the so vilified Southern States—learning the very best lessons for a semi-barbarous people—lessons of self-control, of obedience, of perseverance, of adaptation of means to ends; learning, above all, where their weakness lies, and how they may acquire strength for the battle of life. These considerations satisfy me with their condition, and assure me that it is the best relation they can, for the present, be made to occupy.”

Reviewing the work of the white churches, Frederick Douglass had this to say: “Between the Christianity of this land and the Christianity of Christ, I recognize the widest possible difference—so wide that to receive the one as good, pure, and holy, is of necessity to reject the other as bad, corrupt, and wicked. To be the friend of the one is of necessity to be the enemy of the other. I love the pure, peaceable, and impartial Christianity of Christ; I therefore hate the corrupt, slave-holding, women-whipping, cradle-plundering, partial and hypocritical Christianity of this land. Indeed, I can see no reason but the most deceitful one for calling the religion of this land Christianity…”

Adapted from The Great Stain: Witnessing American Slavery by Noel Rae. Copyright © 2018 by Noel Rae. Reprinted by arrangement with The Overlook Press, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc. http://www.overlookpress.com. All rights reserved.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com