Big factories project an air of solidity and permanence, one reason why states and cities offer millions and even billions of dollars of incentives to attract them. In January, Alabama pledged $379 million in tax abatements, investment rebates, and other benefits to lure a joint Toyota-Mazda assembly plant. Such factories promise large numbers of jobs — 4,000 in the Alabama case — that will revive depressed communities or create whole new ones, ensuring prosperity for many years to come. In the past, all over the world, they have done just that.

But factories have life cycles, and those cycles have gotten shorter and shorter over the three centuries since the first factories sprung up in England. These days, it is often only a matter of decades before factories become outmoded, downsize and shut down, leaving social wreckage behind.

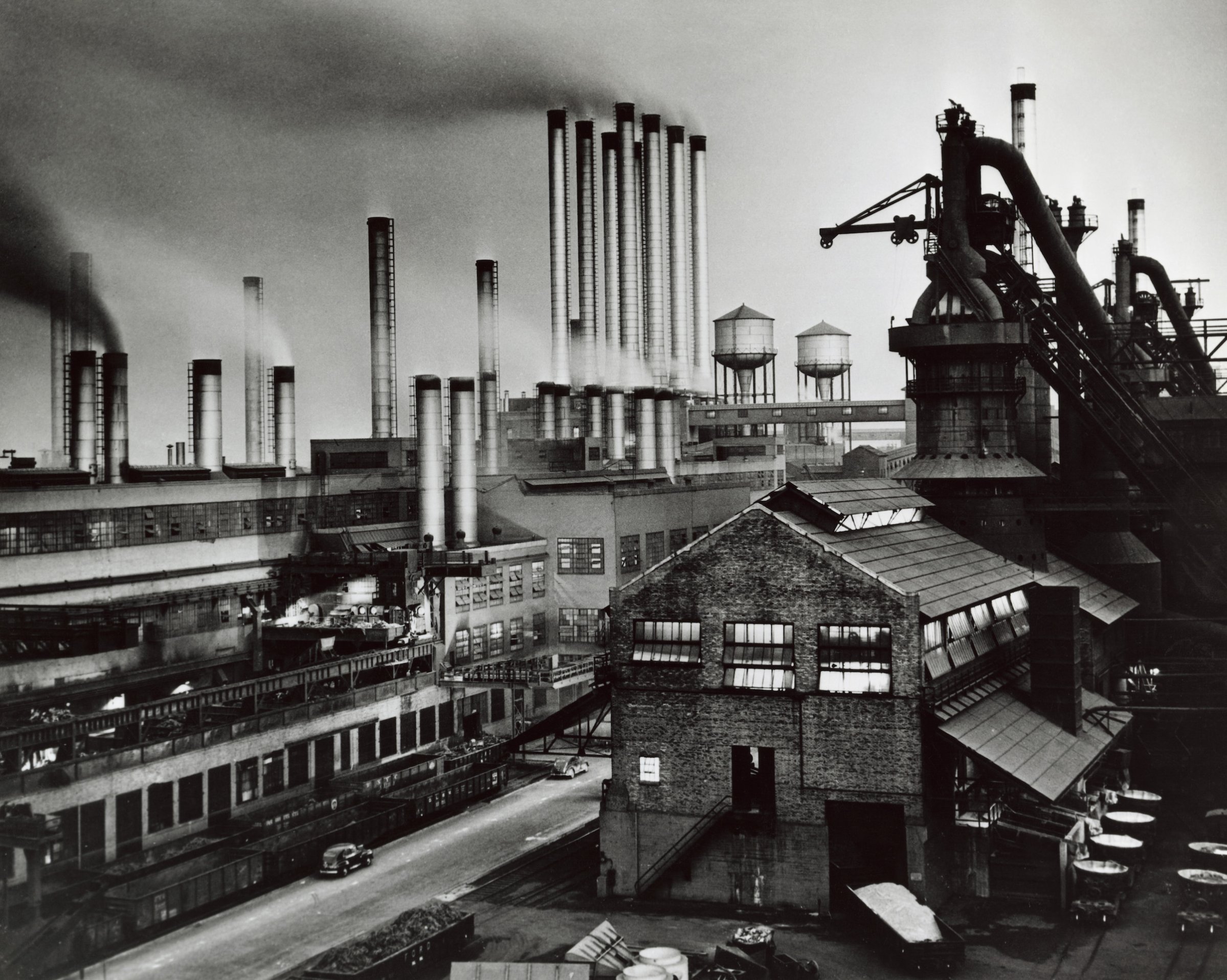

Abandoned or repurposed factories dot the American landscape, from the historic Packard factory in downtown Detroit to the former textile factories in Lowell, Mass. Much the same can be found in northern England and northern France, in the Ruhr Valley, across Eastern Europe, and in Russia and northern China. Many landmark factories still operating have radically shrunk. Ford’s River Rouge plant, once the largest manufacturing complex in the United States, with over 100,000 workers, today produces trucks with just a few thousand workers. Long after their owners have moved on or gone bust, the communities that grew up around large factories often suffer the devastation of unemployment, poverty, shrunken tax revenues, service cuts, pollution and abandonment, painfully evident in cities like Flint, Mich., and Camden, N.J.

This cycle is as old as the factory model itself. Though that production template has been with us since the first modern silk mill opened in Derby, England, in 1721, even the most massive and successful factories rarely have lasted more than a lifetime or two — less time than is common for colleges, churches, mosques, prisons, hospitals, even opera companies.

Big factories tend to arrive in a community with explosive force, their success generally resting not only on technological innovation and economies of scale, but also on the exploitation of workers who had previously existed outside the labor market or in very poorly paid jobs. In the early days, that often meant women and children, displaced peasants, prisoners and wards of the state. These days, migrants from poor areas or victims of regional depressions are commonly hired, grateful for jobs even with long hours, low pay and harsh conditions.

But over time, the advantages of new factories diminish. The vast amount of capital tied up in existing buildings and machinery promotes institutional conservatism, allowing competitors using more advanced methods and technology to become more efficient producers. Meanwhile, worker protest and pressure from reformers pushes up labor costs. At some point, a combination of archaic technology, aging buildings and rising labor costs forces a decision about whether to modernize, start over elsewhere, or milk a property and shut it down. The Derby Silk mill operated for 169 years, a record few factories have matched. The great Homestead Steel Works outside of Pittsburgh lasted for 105 years; the Dodge plant in Hamtramck, Mich., once the second largest automobile plant in America, just 70 years; a 4,000-worker RCA television plant in Memphis a mere five years. Seen globally, the factory has been with us for a very long time, but seen locally, industrial behemoths, with their solid brick walls and soaring metal structures, are only fleeting episodes in the history of particular places.

Today we are seeing this cycle again, at a faster-than-ever pace, in China. Though many Americans bemoan the loss of factory jobs to China, factories built when China opened itself up to foreign investment during the 1980s are beginning to shutter. The Shenzhen region, epicenter for the explosion of Chinese export-oriented manufacturing, already has reached its peak as a center for large-scale production, just 30 years after electronics assembler Foxconn – which operates the largest factories in human history – opened its first plant there. Rising labor and land costs have led manufacturers to move their operations to lower-cost parts of China or abroad. Last year Huajin Shoes, which manufactures footwear for Ivanka Trump, announced that it was shifting some of its production to Ethiopia.

The United States needs manufacturing jobs, and more of them. We do not live in a post-industrial age; globally, manufacturing employment is near an all-time high, even as many American factory jobs have moved abroad, to the detriment of workers. But in trying to bolster manufacturing, the nation’s leaders should learn lessons from the past.

From the moment the possibility of a new factory arises, policymakers should be thinking about what happens when it closes, as inevitably it will.

It can be tempting to think that one big factory could save a town. But one-industry communities are badly hurt when technologies or competitive conditions change, leading to downsizing or closures. The $3 billion dollars Wisconsin has promised to lure a single Foxconn factory might well be better invested in improving conditions that will attract all kinds of manufacturers – and other types of businesses, too. That means better schools and vocational training, improved transportation, low-cost clean energy and affordable housing. Likewise, the temptation to waive environmental or zoning regulations should be resisted, as toxic residue repeatedly has been one of the most difficult challenges communities face after factories leave. Rather than just funneling tax-payers’ money to attract new plants, public entities should think about how to get existing plants to renew and upgrade their facilities and broaden their markets, extending the factory life cycle.

In capitalist societies, investment decisions are almost exclusively made by small groups of corporate leaders, with neither workers nor communities having any direct say. Without fundamental social change, there is only so much policy makers can do. But that is no reason why we have to simply keep doing more of the same. After all, we already know how it turns out.

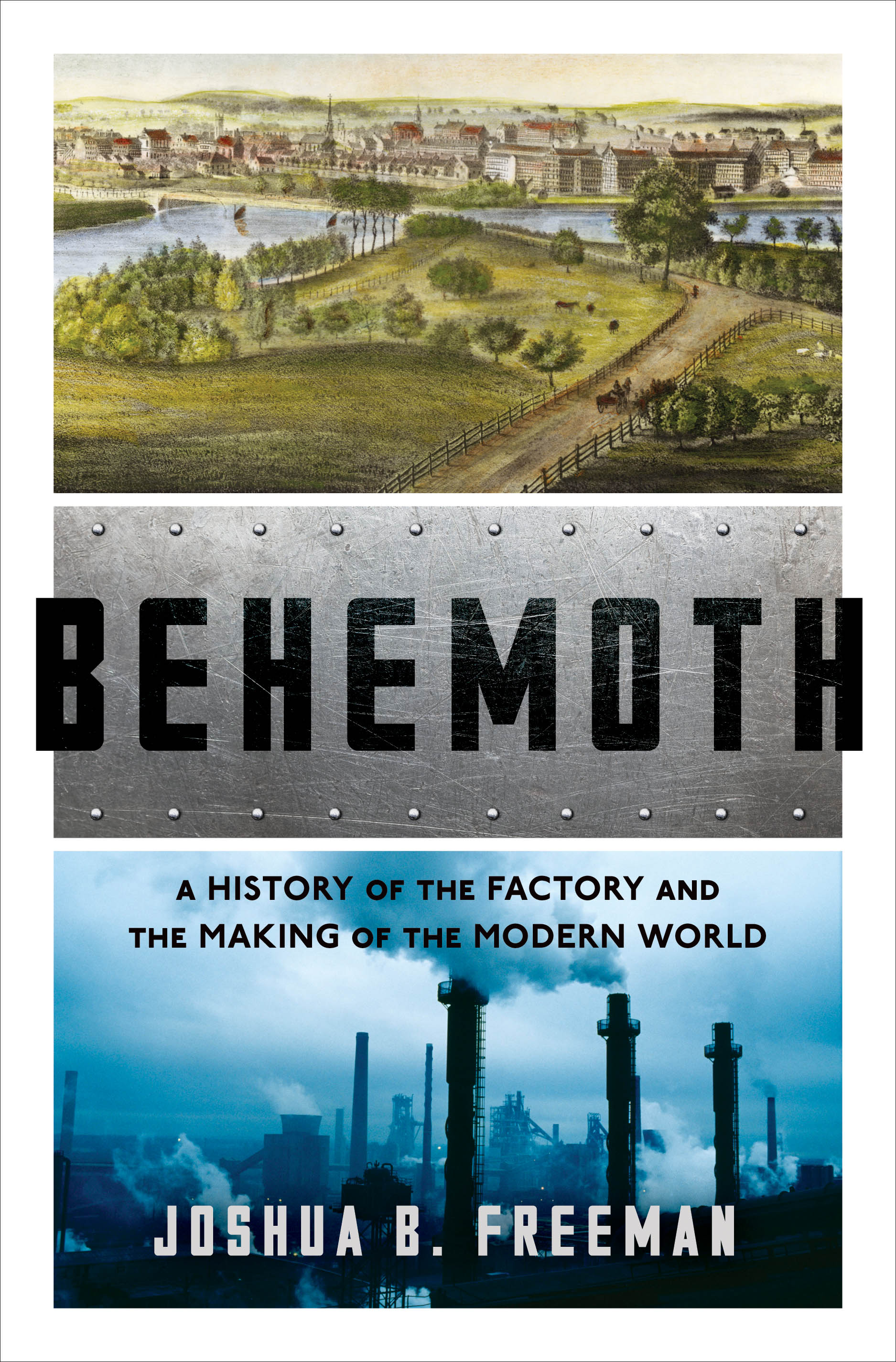

Joshua B. Freeman is the author of Behemoth: A History of the Factory and the Making of the Modern World, available Feb. 27, 2018.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com