You have to climb a steep and narrow road, past the moonshiners’ shacks and dense rhododendrons and through the iron gates to get to the house on the mountaintop that Ruth Graham built after her husband Billy became too famous to live anywhere else. By 1954, after she caught her children charging tourists a nickel to take a picture of their old house and noticed Billy crawling across the floor of his study to keep people outside from catching a glimpse of him, she knew it was time to move.

So up the mountain they went, and now, decades later, the house looks as if it just grew there naturally, instead of being assembled out of pieces Ruth salvaged from older cabins and then put back together like Lincoln Logs. The Graham home is modest in style but had plenty of room over the years for their five children and the family dogs, not to mention the visitors who came by. Fellow preachers and Presidents, moguls and movie stars, icons like Muhammad Ali—all visited with the Grahams here. Bono once showed up and played songs on the piano in the living room. It’s a house of surprise rooms and fireplaces and winding halls filled with souvenirs of their travels. And now it’s a little too quiet.

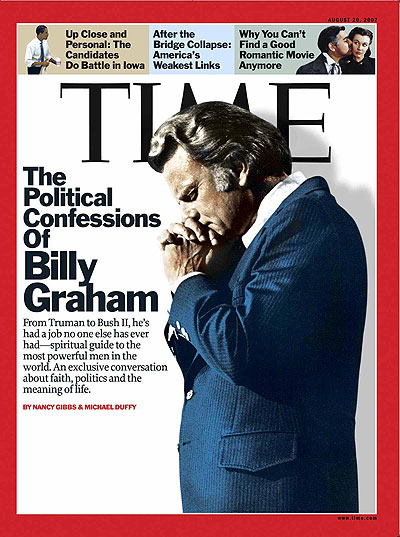

We first met Billy Graham in the winter of 2006, when after long negotiations, we were invited to talk to him about the one topic in his much examined life that he rarely discussed: his intense private and public relationships with every President going back to Harry Truman. He wasn’t doing many interviews anymore, especially since Ruth was now quite ill and he didn’t like leaving her side. But he was willing to share some final lessons and confessions as his life and ministry began to wind down.

At a time when the country was bitterly debating the role of religion in public life, we thought Graham’s 50-year courtship of–and courtship by—11 Presidents was a story that needed to be told. Perhaps more than anyone else, he had shaped the contours of American public religion and had seen close up how the Oval Office affects people. We wondered what the world’s most powerful men wanted from the world’s most famous preacher. What worried them, and what calmed them? “Their personal lives—some of them—were difficult,” he told us. “But I loved them all. I admired them all. I knew that they had burdens beyond anything I could ever know or understand.”

And we wondered, too, how all that time in the White House changed Graham. What temptations did he face, what compromises did he have to make to preserve his access to the Oval Office without becoming a serial prisoner of the men he informally served? In our conversations over the course of 13 months, Graham talked candidly about the dangers of power and politics, about how it was a struggle for him for all those years and about what he learned. “I was aware of the risk at all times, political risk,” he said. “Politics has always been ugly to me, and yet I accept that as a fact of life. The emphasis I tried to leave was love, not … my own love for them but that they need to have love for the people who were opposed to them.”

MATTERS OF LIFE AND DEATH

Billy Graham radiates qualities a president seldom encounters during office hours: innocence, guilelessness, sincerity strong as paint stripper. “I’m not an analyzer,” he told us. “I’ve got a son that analyzes everything and everybody. But I don’t analyze people.” His critics called him gullible, naive to the point of self-delusion; his defenders, of which there were a great many more, called him trusting, always seeing the best in powerful people and frequently eliciting it as a result.

So when Graham was around, Presidents found themselves at ease, not on edge. They could tell that Graham wasn’t there to lobby or confront but to listen and comfort. Because he made it safe to ask the simplest spiritual questions, conversations with Graham had a way of circling around to the eternal, to sin and salvation and to what death really means. Back in 1955, when Dwight Eisenhower had become Graham’s first real friend in the White House, he used to press the evangelist on how people can really know if they are going to heaven. “I didn’t feel that I could answer his question as well as others could have,” Graham told us. But he got better at it with practice. John F. Kennedy wanted to talk about how the world would end–more than an abstract conversation for the first generation of Presidents who had the ability to make that happen.

Lyndon Johnson was obsessed with his own mortality. “He was always a little bit scared of death,” Graham said, and thus wanted a preacher handy–like the time he talked Graham into flying to a convention with him because the weather was so bad, he thought the plane might crash. Having entered office in the shadow of the Kennedy assassination, Johnson was conscious of how a President’s death can shatter a country. Long before his Administration collapsed and he announced that he would not seek a second term in 1968, Johnson privately told Graham what he was thinking. “It was in the family dining room,” Graham recalled, where Johnson reviewed his family’s medical history; he had had a secret actuarial study done in 1967 to predict his life expectancy and determine whether he would be exposing the public to the death of another sitting President. “I may not live through this,” Johnson told Graham. “I’ve already had one heart attack. I don’t think that’s fair to the people or to my party.”

The President even scripted his own exit. One day Johnson took Graham on a walk around his Texas ranch, to a clearing in the trees near where his parents were buried. Johnson wanted to know if he would see them again in heaven. And then another question: Would Billy preach at his funeral? Johnson knew the world listens when a President dies. “Don’t use any notes,” he said, and no fancy eulogizing either. “I want you to look in those cameras and just tell ’em what Christianity is all about. Tell ’em how they can be sure they can go to heaven. I want you to preach the Gospel.” And just one more thing. “Somewhere in there, you tell ’em a few things I did for this country.”

When he got home, Graham wrote to Johnson, expressing his love and reassurance, in case Johnson still had any doubts. “We are not saved because of our own accomplishments,” Graham reminded the President. “I am not going to Heaven because I have preached to great crowds or read the Bible many times. I’m going to Heaven just like the thief on the cross who said in that last moment: ‘Lord, remember me.'”

For a preacher who had no church, and who spent his life preaching to football stadiums full of people he never saw again, the First Families gave Graham the rare chance to be a family pastor. He gave them a sanctuary; they gave him a congregation. He carried the families through times of loss—literal and political; several wanted him to be with them during their last nights in the White House. Richard Nixon collapsed in Graham’s arms at his mother’s funeral in 1967. Bill Clinton took him to sit at the bedside of a dying friend in 1989. Graham was the first person outside the family whom Nancy Reagan called when her husband died in 2004. Last month, Johnson’s daughters Lynda and Luci reached out to him as their mother was dying. Two days before she passed away, he called and talked to them, and since Lady Bird was awake and alert, they put the phone to her ear. The former First Lady and the former White House pastor chatted some and then shared a prayer together.

There’s a reason, Luci Baines Johnson told us, that even First Families of very different political stripes rarely criticize one another. “It’s not necessarily because we’re so classy and nice,” she said. “It’s because we all empathize with each other, with the vulnerability and exposure and the demands on family life. Who needs that kind of life?” Political families could see that the Grahams shared similar burdens as his fame grew while his kids were still at home. “Once you’ve lost your privacy,” Graham observed, “you realize you’ve lost an extremely valuable thing.” That loss touches everyone: “It’s hard on the children because they’re looked at and watched everywhere.” For more than 20 years, Graham’s good friends George H.W. and Barbara Bush invited him and his wife every summer to Kennebunkport, Maine. They were very grateful when he took a walk on the beach one day in 1985 with their eldest son. George W. Bush said that encounter put him on a path to a new relationship with Jesus and “planted a mustard seed” in his soul. But a few years later, he got into an argument with his mother about who exactly could and could not get into heaven. Bush maintained that only born-again Christians were eligible for entrance, as he had been learning in his Bible study; Barbara Bush disagreed and telephoned Graham to let him settle the matter. The evangelist said that while the younger Bush’s reading of the Bible might be technically correct, he warned both of them that no one should try to play God—for God alone knows who has or has not received Christ as their Saviour.

THE GREAT TEMPTATION

But how far could a pastor go without becoming part of the political game? Graham was the most famous preacher on earth. Simply by standing next to Presidents, he conferred a blessing both on them and on their policies. Every one of them was aware of this, in ways that Graham sometimes was not. Was it crossing a line when he invited presidential candidates to his crusades or sent along suggestions for their speeches at National Prayer Breakfasts? What about when he lobbied lawmakers on behalf of a poverty bill or an arms deal, or consulted with candidates on their campaign ads or their running mates? It was one thing to serve as Eisenhower’s or Johnson’s private pastor. But it was quite another to act as Nixon’s political partner, carrying private messages to foreign heads of state, advising on campaign strategy and assembling evangelical leaders for private White House briefings.

There were times when Graham brought out the best in Nixon–and times as well when Nixon brought out the worst in Graham, most notoriously in the hideous February 1972 conversation in which Nixon went on about how the Jews who controlled the media were destroying the country and Graham went along. It was an exchange so vile, it raised the legitimate question of what exactly a President would have to do for Graham to stop consoling and begin confronting him on moral grounds. “I did misjudge him,” Graham told us, and the pain of what he had said in the rarefied air of the Oval Office clearly still lingered more than 35 years later. “I don’t understand it,” he said. “I never thought that way, and I was just trying to agree with what he said or something.”

A fiercely partisan Democrat told us that Graham, a registered Democrat all his life, wasn’t complicated once you realized he was actually just a Republican. But that’s too simple an explanation. Graham liked all the Presidents and regarded them first and foremost as his friends—with the intriguing exception of Jimmy Carter. The fellow born-again Southern Baptist was the only President ever to organize a local Graham crusade. But on the heels of Graham’s crushing experience with the Nixon Administration, the evangelist recalibrated his relationship with the White House and kept his distance. “I looked on Carter as the President,” Graham said. As other evangelical leaders emerged to play more muscular roles in politics in the late 1970s, Graham tried to warn them about the dangers they faced. In 1981 he declared that “Evangelicals can’t be closely identified with any particular party or person. We have to stand in the middle, to preach to all the people, right and left. I haven’t been faithful to my own advice in the past. I will in the future.”

From then on, Graham operated below the radar as three old friends—Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton—took their turns in the Oval Office. To his critics, the pastoral was political. The left deplored his spending the night with Bush on the day the Gulf War began; the right objected to his praying at Clinton’s Inaugural. But Graham stood by them all, including his old charge George W. Bush, whom he publicly embraced on the final Sunday before the 2000 election–in Florida, of all places.

LESSONS OF A LIFETIME

When we went back for a final conversation in January 2007, it was clear that the pressure on Bush was also weighing on Graham. He said he did not want to “take sides on this Iraq thing,” but he kept returning to the war in our conversation, without mentioning that his grandson was an Army Ranger serving there. “I’m getting a little depressed about Iraq,” Graham admitted at one point. “Think of what it is doing to Bush. There doesn’t seem to be any way out.” The President, he said, had reached out in recent months on different subjects, trying to arrange a White House lunch or visit. “We’ve postponed it three times now. I’ve not been able to do it because of my wife. I felt badly.”

Graham still was following politics, albeit from a safe distance now. Though he has never met John McCain, the evangelist recalled stopping in Hawaii on his trips to and from South Vietnam and praying on his knees next to McCain’s father Admiral John McCain, then commander of U.S. forces in the Pacific, for the son who was being held as a prisoner of war. He watched Mitt Romney wrestle with the Mormon question. “It will be somewhat of a problem for him, like Jack Kennedy being a Catholic,” Graham predicted, although he believed Romney could overcome it by directly addressing the concerns as Kennedy did. Graham was also keeping a close eye on the progress of Hillary Clinton, whom he knows the best of all the candidates. “I keep up with her,” he said of his old friend. “I think a lot of Hillary.”

That feeling is mutual: Clinton first met him in person when she was First Lady of Arkansas, but they became close when she was First Lady of the United States. She needed some pastoral care of her own in 1998, at the height of the Monica Lewinsky scandal, and became the latest public figure to sense Graham’s unique attraction to the occupants of the Oval Office. He was, she concluded, a political junkie himself. “He loved elections,” she told us, “because he knew that you had to tell a story, you had to connect with people–all the things we talk about in politics.” To the Presidents, Graham’s fame and charisma made him a virtual peer: “I think there was a recognition there, and a comfort, with dealing with someone who was a public person,” Clinton observed, “who had to put up with what’s wonderful about being in the public eye and what’s kind of a drag.”

We see Presidents fight so hard to win the office, but we often forget the price they pay to hold it. If Graham helped raise these men up, he also caught them after they returned to earth. “Every President I think I’ve ever known, except Truman, has thought they didn’t quite get done what they wanted done,” Graham said. “And toward the end of their Administrations, they were disappointed and wished they had done some things differently.”

Graham recalled these friendships with the humility that comes with experience. “As I look back, I feel even more unqualified–to think I sat there and talked to the President of the United States,” he said. “I can only explain that God was planning it in some ways, but I didn’t understand it.” He doesn’t expect to make it back to the White House anytime soon, but he watches out for its occupant the best way he knows how. He does daily devotions, and whoever sits in the Oval Office will always have a place in his prayers.

Adapted from The Preacher and the Presidents by Nancy Gibbs and Michael Duffy. © 2007 by Nancy Gibbs and Michael Duffy. To be published by Center Street

This article appears in the Aug. 20, 2007, issue of TIME

More Must-Reads From TIME

- What Student Photojournalists Saw at the Campus Protests

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Why Maternity Care Is Underpaid

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Scientists Are Finding Out Just How Toxic Your Stuff Is

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com