Drug overdoses kill more than 64,000 people per year, and are now the leading cause of death for Americans under 50. To document the nation’s devastating opioid crisis, TIME sent photographer James Nachtwey and deputy director of photography Paul Moakley across the country to gather stories from the frontlines of the epidemic. The result, The Opioid Diaries, is a visual record of a national emergency and a call to action.

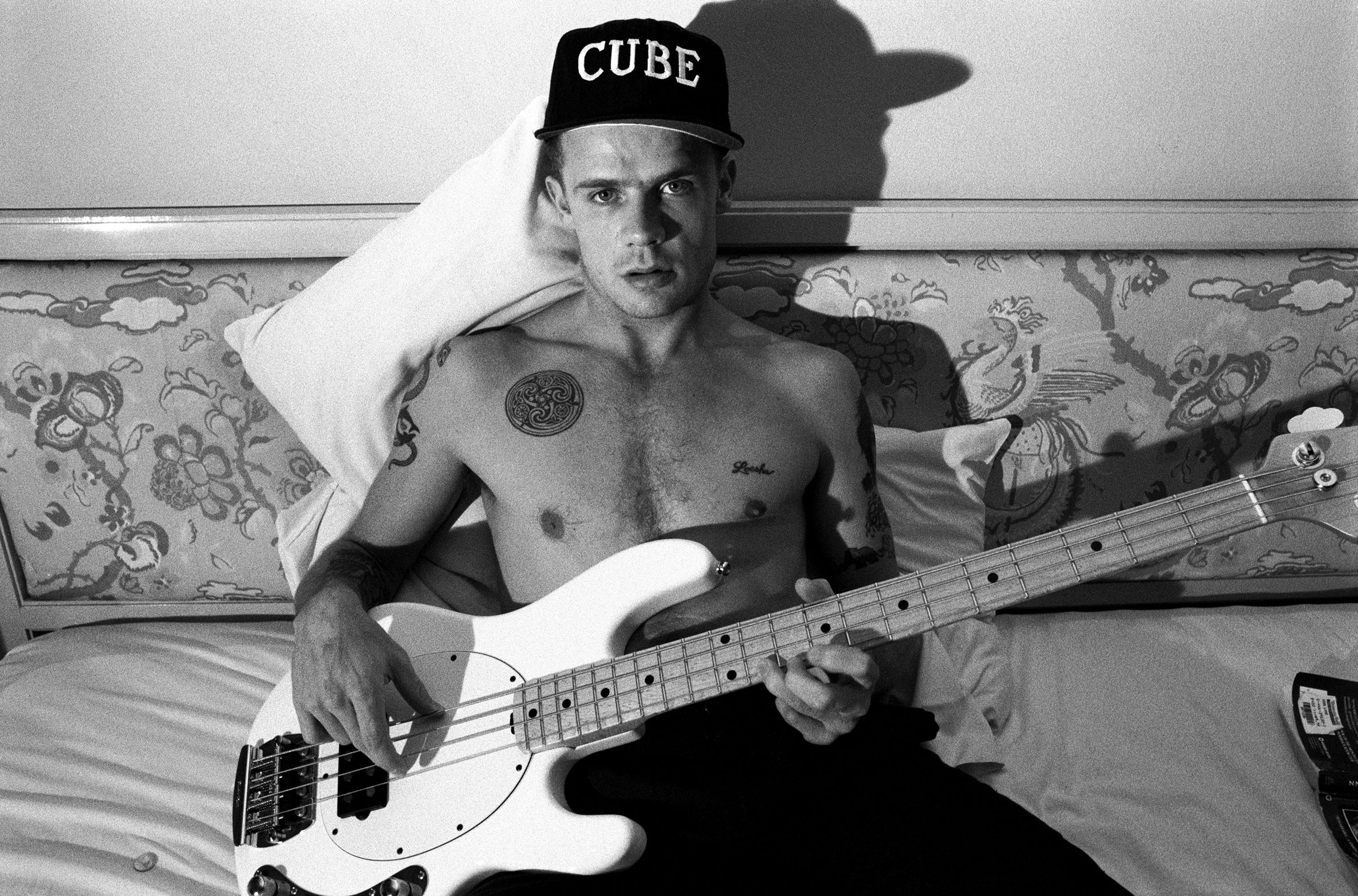

I’ve been around substance abuse since the day I was born. All the adults in my life regularly numbed themselves to ease their troubles, and alcohol or drugs were everywhere, always. I started smoking weed when I was eleven, and then proceeded to snort, shoot, pop, smoke, drop and dragon chase my way through my teens and twenties.

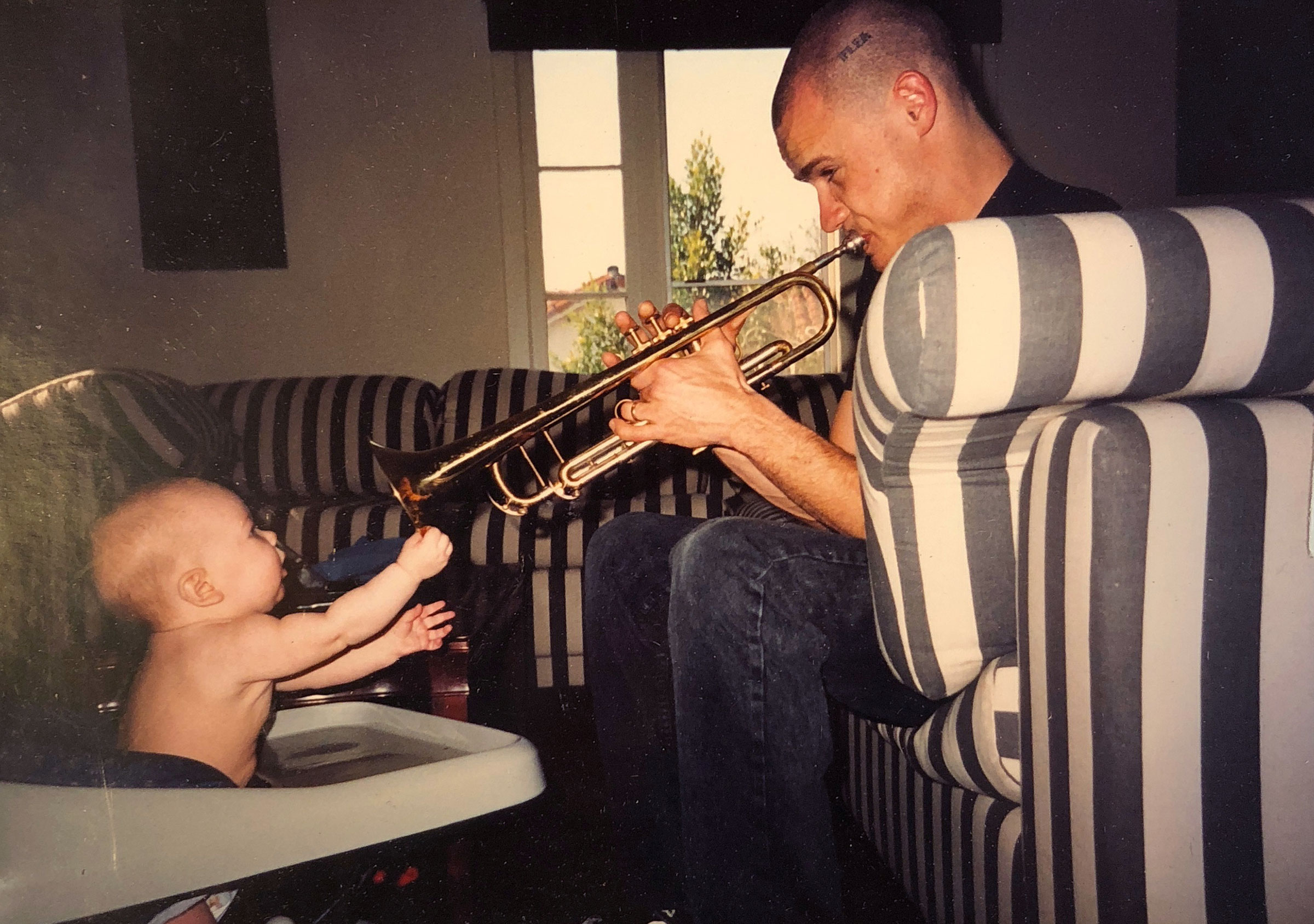

I saw three of my dearest friends die from drugs before they turned 26, and had some close calls myself. It was a powerful yearning to be a good father that eventually inspired a sense of self-preservation, and in 1993 at the age of 30 I finally got that drugs were destructive and robbing my life force. I cut them out forever.

Temptation is a bitch though. All my life I’ve gone through periods of horrific anxiety: a tightness in my stomach that creeps up and squeezes my brain in an icy grip. My mind relentlessly whirring, I can’t eat or sleep, and I stare into a seemingly infinite void of despair, a bottomless pit of fear. Ouch. Man, drugs would fix all that in a flash.

Once you’ve opened the door to drug abuse, it’s always there, seducing you to come on in and get your head right. I can meditate, exercise, pray, go to a shrink, work patiently and humbly through my most difficult relationship problems, or I could just meet a dealer, cop a bag of dope for $50 and fix it all in a minute.

What I’ve learned is to always be grateful for my pain. That mindset has helped me stay away from the temptation of drugs.

I didn’t get clean through rehab or a 12-step program. I believe wholeheartedly in organizations like AA, but that was not my path. What worked for me was learning that the best way to grow is to consciously experience the hard times. I had a burning desire for good health and love, and found that I had to go through periods of suffering to get there. That realization was not easy, but it freed me up to have faith in myself. A clear head has allowed me to walk through to the other side of pain and addiction, and there I’ve found real success, joy and strength.

But back when I was a petty thievin’ Hollywood street urchin running feral, and doing every drug in the book, the dangers were clear. Cops busted me, drug dealers burned me, accidental overdoses happened and scary gun-toting criminals lurked in the shadows. To step into this seedy world of narcotics was obviously dangerous.

But what if your dealer was someone you’d trusted to keep you healthy since you were a kid? Many who are suffering today were introduced to drugs through their healthcare providers. When I was a kid, my doctor would give me a butterscotch candy after a checkup. Now, they’re handing out scripts. It’s hard to beat temptation when the person supplying you has a fancy job and credentials and it’s usually bad advice not to trust them.

A few years ago I broke my arm snowboarding and had to have major surgery. My doctor put me back together perfectly, and thanks to him I can still play bass with all my heart. But he also gave me two-month supply of Oxycontin. The bottle said to take four each day. I was high as hell when I took those things. It not only quelled my physical pain, but all my emotions as well. I only took one a day, but I was not present for my kids, my creative spirit went into decline and I became depressed. I stopped taking them after a month, but I could have easily gotten another refill.

Perfectly sane people become addicted to these medications and end up dead. Lawyers, plumbers, philosophers, celebrities — addiction doesn’t care who you are.

There is obviously a time when painkillers should be prescribed, but medical professions should be more discerning. It’s also equally obvious that part of any opioid prescription should include follow-up, monitoring and a clear solution and path to rehabilitation if anyone becomes addicted. Big pharma could pay for this with a percentage of their huge profits.

Addiction is a cruel disease, and the medical community, together with the government, should offer help to all of those who need it.

Life hurts. The world is scary and it’s easier to take drugs than work through pain, anxiety, injustice and disappointment. But by starting with gratitude for the rough times, and valuing the lessons of our difficulties, we’ve got the opportunity to rise above them and be healthier and happier individuals who live above the strong temptation of addiction.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com