Drug overdoses kill more than 64,000 people per year, and are now the leading cause of death for Americans under 50. To document the nation’s devastating opioid crisis, TIME sent photographer James Nachtwey and deputy director of photography Paul Moakley across the country to gather stories from the frontlines of the epidemic. The result, The Opioid Diaries, is a visual record of a national emergency and a call to action.

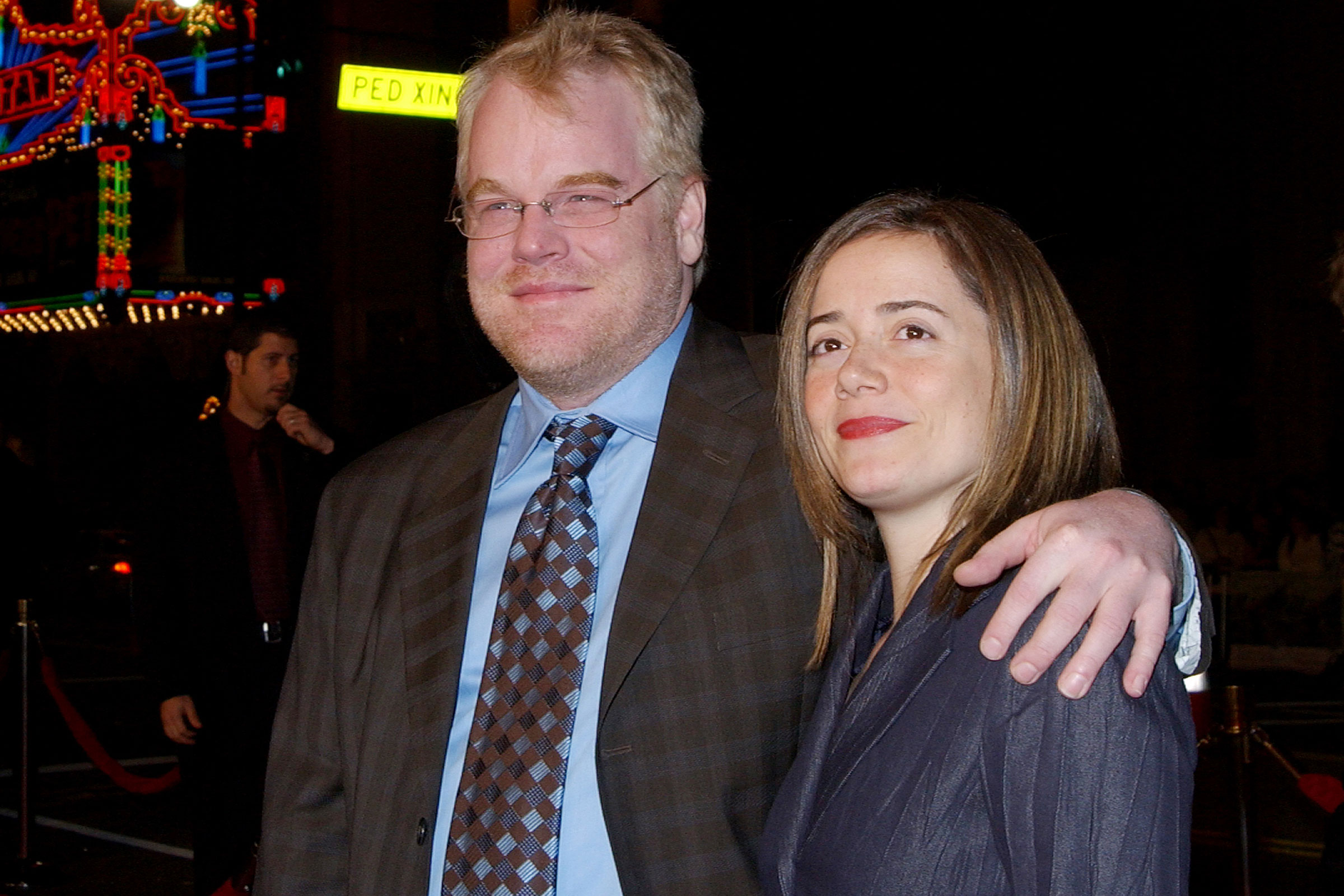

When I lost Phil to a drug overdose, I found that I couldn’t begin to move on until I started to forgive. I had to forgive myself, him and anyone I thought could have done more to prevent the final outcome. In order to forgive, however, I had to let the emotions of anger, guilt and shame play out. When Phil died four years ago, I was so overwhelmed, vulnerable and cracked open that anger became my protective shield, the only thing between me and collapse.

When Phil relapsed, like so many others, I felt alone and shocked, and didn’t know where to turn for help. I was also ashamed to ask for help. And shame is powerful. It keeps addiction hidden and allows it to continue. I wondered if I had talked to more people, asked for more help — screamed louder — if it would have saved his life. When he died, I and many around him, felt so guilty. There’s this guilt of not doing more that I think is inevitable. But time really does heal, and as it’s passed, over the last year or two, I’ve started to understand how to forgive.

One of the initial things that helped soften my anger was physically letting go of his belongings. When Phil died, I kept every receipt, cigarette butt anything he touched as a way to hold onto his memory. It took a long time for me to accept that he was never coming home again. But life has a way of nudging you forward and about a year and a half after he passed, I discovered a moth infestation in my apartment. I opened the closet where many of Phil’s clothes were, and most of them were full holes. As I began to remove his physical things, my anger started to subside and other emotions, more softer and vulnerable ones, started to come in. I had to fully accept that Phil’s death was final. I also had to accept that I was now a single mother of three, something I did not want, but that’s where I was. Forgiveness is attached to ego; it’s humbling.

I also had to own how Phil passed. It was hard enough to utter the word “dead” and even more difficult to say the cause was a heroin overdose. But saying it has been very powerful for me and for my kids. It has allowed us to start to shed the shame. Still, forgiving Phil has not been easy. When he was using, I was furious and fearful. But at the same time I loved him, and had to balance these extreme emotions. I have continued to feel these extreme emotions even after his death, but I’ve come to realize that under the intense anger is the plain fact that I miss him. I wish he was still here.

Raising our children every day has also helped me to heal. They are astounding human beings, and I see Phil in each of them. I’ve also come to understand the most basic truth, that the world and life go on, and we are here for such a short time. I am beyond grateful for my life with Phil. Most of the wonderful things I have are because of him, including my kids, and that’s enough. Even though the addiction was destructive, what he did when he was alive is still here. It’s still relevant. It’s still happening. It’s this awareness that’s helping me forgive and move on.

Forgiveness also let me set aside blame. When we’re blaming ourselves, the addict or the system, judgement comes into play and that stunts the conversation of how we can truly address this brutal problem.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com