JoAnn Wooding is staring intently at the clear liquid dripping from a dark brown IV bag into her husband Peter’s arm. “Please be the drug, please be the drug,” she says. Married for more than 50 years, the Woodings are among the more than 5 million Americans who are facing Alzheimer’s disease, one of the most devastating diagnoses today.

But instead of accepting the slow descent into memory loss, confusion and dementia, Peter–who has the disease–could be among the first to successfully stop that decline from happening.

Peter, 77, is one of the 2,700 people around the world who are expected to volunteer to test what researchers believe could be the first drug to halt Alzheimer’s. Two-thirds of the volunteers will receive the drug, and one-third will get a placebo. They won’t know which one they received until they have participated for 18 months.

While there are genes that contribute to a higher risk of Alzheimer’s, for most people, age is the biggest risk factor for the disease. The human brain is remarkably resilient, but only up to a point. With time, connections that normally call up a memory or help remind people where they are start to get weaker. The first symptoms might be as innocuous as forgetting where you left your phone or missing an appointment. In most cases, the first memories to slip away are more recent ones. Slowly, sophisticated tasks such as organizing a trip, paying bills or driving to familiar places become more challenging. Important birthdays and milestones that you have celebrated your entire life start to slip away, and eventually you stop recognizing your loved ones.

Currently, 1 in 10 people in the U.S. over age 65 has Alzheimer’s. By 2050, without an effective treatment, 16 million could be affected by the disease. Worldwide, about 50 million people have dementia, most of it due to Alzheimer’s, and that number doubles every 20 years.

The memory-robbing brain disorder has proved vexingly hard to treat. Dr. Alois Alzheimer first described the condition in 1906, but in the more than 100 years since, scientists have not been able to develop any effective treatments. Part of the reason has to do with biology; finding and targeting something in the brain without compromising the delicate network of activities that keep us breathing, thinking and moving every day is a daunting task. Despite the fact that the market for Alzheimer’s drugs could reach an estimated $30 billion in the U.S. alone, drugmakers have already squandered hundreds of millions of dollars, if not billions, in chasing after an effective treatment.

There is also a stigma surrounding the disease. Surveys consistently show that people of all ages are universally afraid of developing the condition, yet with the degenerative brain disorder, unlike conditions such as cancer and heart disease, there is little public discussion about how it transforms not just patients’ lives but the lives of their families as well. It was not until 2012 that President Obama created the first national plan to address the disease, which set a goal of finding ways to prevent and treat Alzheimer’s by 2025. As a result, funding for Alzheimer’s research at the National Institutes of Health, for example, has more than doubled in recent years.

That shift in attention toward Alzheimer’s makes researchers hopeful for the first time in decades that they are finally making headway against the disease. The drug Peter is testing is designed to chip away at amyloid, the protein that builds up in the brains of people affected by Alzheimer’s, and break down the sticky plaques that may eventually strangle healthy nerve cells and shut down critical circuits for memory, reasoning and organizing. In early studies, aducanumab, as the experimental drug is called, shrank the plaques in the brain, and some people who took it for up to three years showed slower declines in memory and thinking skills on certain mental tests.

The Woodings are hoping that Peter sees the same benefit. Which is why JoAnn is fervently hoping that her husband is one of the fortunate ones receiving the promising medication.

“It’s hard to measure the cumulative effect of losing one’s memory,” says Peter, reflecting on how his disease has affected his life. “And my memory is not completely gone, by the way. Just certain aspects of it. Retrieval of information is slower, and my reaction time and mental processing time is slower.”

Both industrial designers, Peter and JoAnn ran their own design firm for nearly 40 years, creating products for the home and office as well as designing commercial and residential spaces, including converting Union Station in Providence, R.I., into a corporate headquarters. Their home in Massachusetts bears witness to their work, from the prototypes of sleek armchairs and sofas designed for Knoll to the flatware they created for Dansk in their kitchen. Peter also served as president of the Industrial Designers Society of America (IDSA), frequently lecturing abroad. And as a faculty member at Rhode Island School of Design, he tackled the issue of designing accessible furniture and appliances for people with disabilities.

But after Peter took a bad fall in the early 2000s, JoAnn began noticing changes in her husband’s memory. Never known for his perfect recall, he was having trouble keeping track of deadlines for projects and what was discussed at meetings.

In the spring of 2016, they took advantage of a study in which Medicare covered the cost of brain scans of older people to check for amyloid, the protein that is the hallmark of Alzheimer’s. In the scans, it was undeniable–Peter had Alzheimer’s.

“It was definitely a big shock,” he says. “You could see it in the scans, this white cloud that covered my brain.”

Putting his solution-oriented design skills to work, Peter immediately began looking for ways to be proactive about the impending cognitive decline. “What do you do? Do you bundle up and fall through a manhole and lose it forever? No. Beating this thing has become the No. 1 priority for me,” he says.

JoAnn read a newspaper article about the new study at Butler Hospital in Providence, where the Woodings lived at the time, and they asked to join. “I felt like it was a responsibility, that if I could participate and contribute, my experience would hopefully lead to some further understanding of this disease and some potential solution,” says Peter of his decision to volunteer for the study.

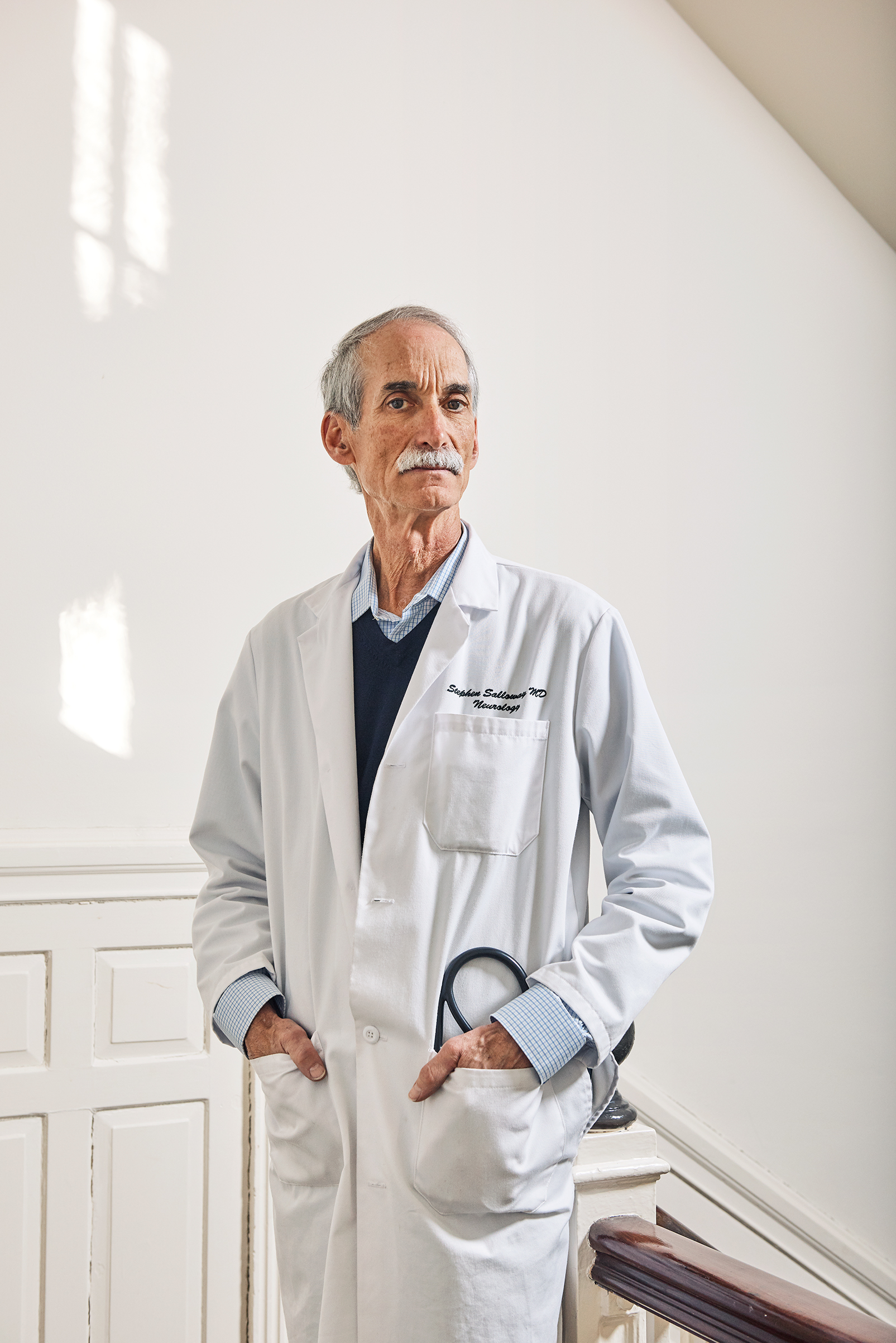

He agreed to receive injections of either the drug or a placebo once a month for a year and a half. After that, he is guaranteed to receive the drug for two more years. It won’t be until 2020, when all the people in the study have completed their injections, that the Woodings and their doctor, Stephen Salloway, who is leading the study at Butler, will learn whether he received the drug or a dummy solution.

So far, Peter has received 16 infusions. The Woodings realize that while the odds are better than even that he has been getting the drug that could slow his disease, it’s also possible that they have given Alzheimer’s more than a year’s head start. “I worry that he is getting the placebo,” says JoAnn. “I see any change in him as an indication of perhaps that’s exactly what’s happening. Even if he gets the drug 18 months later, he will have lost ground.”

“Not if I have anything to say about it,” says Peter.

Even if Peter is getting the placebo, the Woodings recognize that they are fortunate to have the opportunity to test a potentially promising drug. Peter is still in the early stages of the disease, when doctors believe they have the strongest chance of at least keeping the changes in his brain from getting worse. And it turns out that the Woodings came to Butler at an opportune time. If his memory problems had shown up even a decade earlier, he would have had a paltry array of options for combatting the disease. There were no treatments then, and there were relatively few promising experimental drugs even being tested to treat Alzheimer’s.

In the early 2000s, research in the field had come to a near standstill. Scientists knew that amyloid, a protein made by cells in the brain, seemed to build up abnormally in the brains of people with the disease, eventually strangling nerve cells to death by cutting them off from the essential nutrients they need to survive. A highly vaunted and anticipated trial of a vaccine designed to wipe away amyloid plaques failed to produce much change in the memory and cognitive state of the people testing it in a study, and a series of other anti-amyloid drugs also seemed to do little to reverse the overpowering deposits of amyloid.

The company behind the vaccine, Elan Pharmaceuticals, refused to give up, however, and joined with Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson to develop another amyloid fighter, this one an injectable drug. The researchers tested it in people with a genetic mutation that puts them at high risk of developing Alzheimer’s. But as with the vaccine, the results were disappointing. In cognitive tests, the people receiving the drug did no better than those getting a placebo.

Recently, Eli Lilly announced underwhelming results of its drug that was supposed to break up amyloid; no difference was seen between people who received the drug and those who did not on their scores on cognitive tests or their ability to complete daily activities such as balancing a checkbook or keeping track of appointments.

The string of failures was enough to prompt some brain experts to question whether the theory that amyloid plaques cause Alzheimer’s was correct. If all the anti-amyloid drugs weren’t having an effect on the disease, then maybe amyloid wasn’t the right target, they argued.

But there could be other reasons those trials failed. For one, some of the people in the studies showed signs of dementia but may not have had Alzheimer’s or amyloid plaques at all. Because it’s hard to tell the difference between normal, age-related problems of memory and brain functioning from those caused by the buildup of amyloid, some of the people in the studies of anti-amyloid drugs may not have had amyloid in their brains in the first place. In those cases, it wouldn’t be surprising that the drug didn’t have an effect on their thinking skills, since the drug would not have been acting on amyloid.

It’s also possible that the drugs may simply have been given too late in the disease and in doses that were too low. Because the people in the study had to have memory problems in order to qualify for an Alzheimer’s drug trial, by the time they took the experimental anti-amyloid drugs, there may have been too much amyloid already built up in their brains, making it hard for the drugs to dissolve it. It would have been like trying to melt an iceberg with a hair dryer; the burden of plaques was too overwhelming.

Finally, and perhaps most important for the development of new drugs, scientists now know that while autopsy studies have showed that amyloid plaques are a common feature of people with Alzheimer’s, not everyone with amyloid deposits in the brain necessarily develops the disease. Some people have a natural ability to keep the plaques from building up or are able to make less amyloid, so the protein doesn’t aggregate into toxic clumps.

In fact, studying those people led to the drug that Peter is testing. Developed by Biogen and Neurimmune, it came from older people who either did not develop Alzheimer’s or showed much slower rates of cognitive decline than average Alzheimer’s patients did. “Something was retarding the Alzheimer’s or protecting against Alzheimer’s in these older people,” says Salloway, the Woodings’ doctor and the director of neurology and the Memory and Aging Program at Butler. In a lab, that something was turned into aducanumab.

That provenance means there is a stronger chance that the same natural process helping those people could help others slow Alzheimer’s as well. The drug is also unique among the amyloid busters that came before. Amyloid starts out not as a sticky wad of gumlike protein but as thin strands that float in the spinal fluid and blood. Earlier amyloid drugs were designed to attach and remove these fibrils, so some Alzheimer’s experts believe that these drugs didn’t translate into changes in people’s memory or cognitive function because while the smaller circulating pieces of amyloid were eliminated, the larger plaques remained intact. Once these amyloid aggregates reach critical mass, they trigger another toxic process known as tau tangles. Tau is another protein that attaches leechlike onto the long arms of nerves, destabilizing them until they shrivel up into a tangled mess. If the nerves are no longer aligned properly and communicating with one another, they die. In the same way that a home ravaged by fire generally can’t be saved, even if drugs can destroy the new, circulating forms of amyloid, if enough amyloid plaques and tau tangles have already formed, the damage to the nerve cells and their connections can’t be reversed.

To avoid that problem, aducanumab is designed to be more aggressive in attacking the established plaques of amyloid. That may prove more practical, since by the time people complain of memory problems and Alzheimer’s symptoms, they likely already have significant amounts of plaques in their brains. “This is the first amyloid-based treatment to show this degree of amyloid lowering,” says Salloway.

And it’s not just the drugs that are getting better. Since 2011, researchers have had a way to see the amyloid in the live brain, something they could do before only in an autopsy. Peter received an amyloid PET scan of his brain before beginning the study and continues to get scans periodically. His doctors can not only verify that his brain contains the plaques but also track changes in their size to learn whether the drug he is testing is shrinking them or not.

Doctors don’t expect aducanumab to reverse damage already caused by Alzheimer’s, but if it is the first to stop the disease from progressing, that would be a huge step toward controlling it. “We don’t need a home run,” says Dr. Pierre Tariot, director of the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute and a professor of psychiatry at the University of Arizona. “If we can get some traction and slow the train down, that would be a tremendous therapeutic victory, even if we don’t completely stop the train in its tracks.”

For the Woodings, that would indeed be a victory. As part of the study, they learned that Peter, like 25% of people around the world, carries one copy of the APOE4 gene, so what is happening in his brain is in part genetic. His DNA doubles or triples his risk of developing Alzheimer’s, compared with someone without the same gene. (People with two copies of APOE4 have a risk of developing the disease eight to 12 times as great as those with other versions of APOE.) Two years ago, he and JoAnn stepped away from day-to-day responsibilities at their design business, essentially turning it over to their son Rob. While Peter still drives, he says it’s getting more challenging to navigate. “I had an excellent sense of direction when driving,” he says. “That has gone away now. I’m less skillful in that.” JoAnn won’t let him drive unless she’s also in the car with him, in case he gets lost.

She has also seen other signs of Peter’s forgetfulness, which has rearranged their lives in ways they never anticipated. Now, says JoAnn, “if I have to go to have my hair cut, Peter goes with me. And if he goes to have his hair cut, I go with him. We’re together 24/7, and we go everywhere together, with few exceptions.”

Last year, when he was still driving alone, JoAnn waited for Peter to return from a trip to the gym so she could use the car for an appointment. Peter didn’t get home on time, and JoAnn had to call a cab. She learned later that he was buying her a Valentine’s Day card–having forgotten that they had already purchased cards the day before.

Whether or not the drug Peter is testing is successful, researchers are convinced that it could be an important part of the Alzheimer’s arsenal in the coming years. They are pursuing two new strategies for halting the disease: introducing treatments like aducanumab earlier, before the amyloid plaques and the tau tangles damage nerve cells, and combining various strategies to increase their chances of success.

Starting people on Alzheimer’s treatments earlier in their disease is something that has become possible only in recent years, since doctors can now see, with the latest brain-imaging scans, the first signs of amyloid building in the brain. “Nerve cells are not easy to resuscitate or restore or reinvigorate,” says Salloway. “So we’ve got to try to catch it early–before there is a lot of memory loss and decline in functioning.”

They are learning from their colleagues in cancer and HIV who have successfully combined so-so drugs to get a more sustained effect, and they are encouraged by the potential power in combining different Alzheimer’s drugs. That means every drug like aducanumab counts. “The hope is that if we combine treatments, we may see the kind of boost in efficacy that we all hope to see one day,” says Dr. James Hendrix, director of global science initiatives at the Alzheimer’s Association. “I think the best promise for the future is in combinations of drugs.”

There’s an urgency to fulfill that promise, as the number of people hitting their 70s and 80s, when Alzheimer’s is most likely to develop, is starting to balloon. And making sure that the aging population doesn’t become an Alzheimer’s population isn’t just about finding the right medicines to treat the disease. It’s also about making sure that people are doing what they can to keep their brains healthy and active in the decades leading up to older age–by getting regular exercise, remaining socially active and engaging their brain in new activities. In studies, for example, people like Peter who carry one of the high-risk genes for Alzheimer’s but exercise regularly show more activity in their brain than people with the gene who don’t exercise as much.

Peter is doing his part. He and JoAnn visit the local YMCA almost every day and spend about an hour circuit training and using the stationary bikes and treadmills. They are also sticking with their Mediterranean diet, which is heavy on the fruits and vegetables that can keep down inflammation, one of the potential triggers of amyloid buildup. Peter also tries to play computer brain games as often as he can and reads voraciously.

His long-term memory is still intact, and he is able to remember the names of people he met on long-ago trips he made while president of the IDSA. It’s the short-term memory that seems to slip away more quickly. “I want to keep Peter as Peter for as long as possible,” JoAnn says.

Time has become precious for them, and their bond has become stronger as they adjust to a new life with Peter’s Alzheimer’s. Since his drawing skills are intact, JoAnn is encouraging her husband to go back to painting. They are optimistic that their decision to join the study will not only help people who are affected by the disease in the future but might benefit Peter as well. “Realistically, I know that there hasn’t been a lot of data on a cure,” says Peter. “So that’s what we’re waiting for hopefully–a cure. Let’s end Alzheimer’s.” Says JoAnn: “What is the point of living if you don’t have hope? Hope is everything. So we continue to hope.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com