Last month, supervised injection facilities, also known as safe injection facilities (SIFs), were thrust back into the news when Philadelphia officials announced the city would likely become the first in the U.S. to adopt the controversial tactic for fighting opioid abuse.

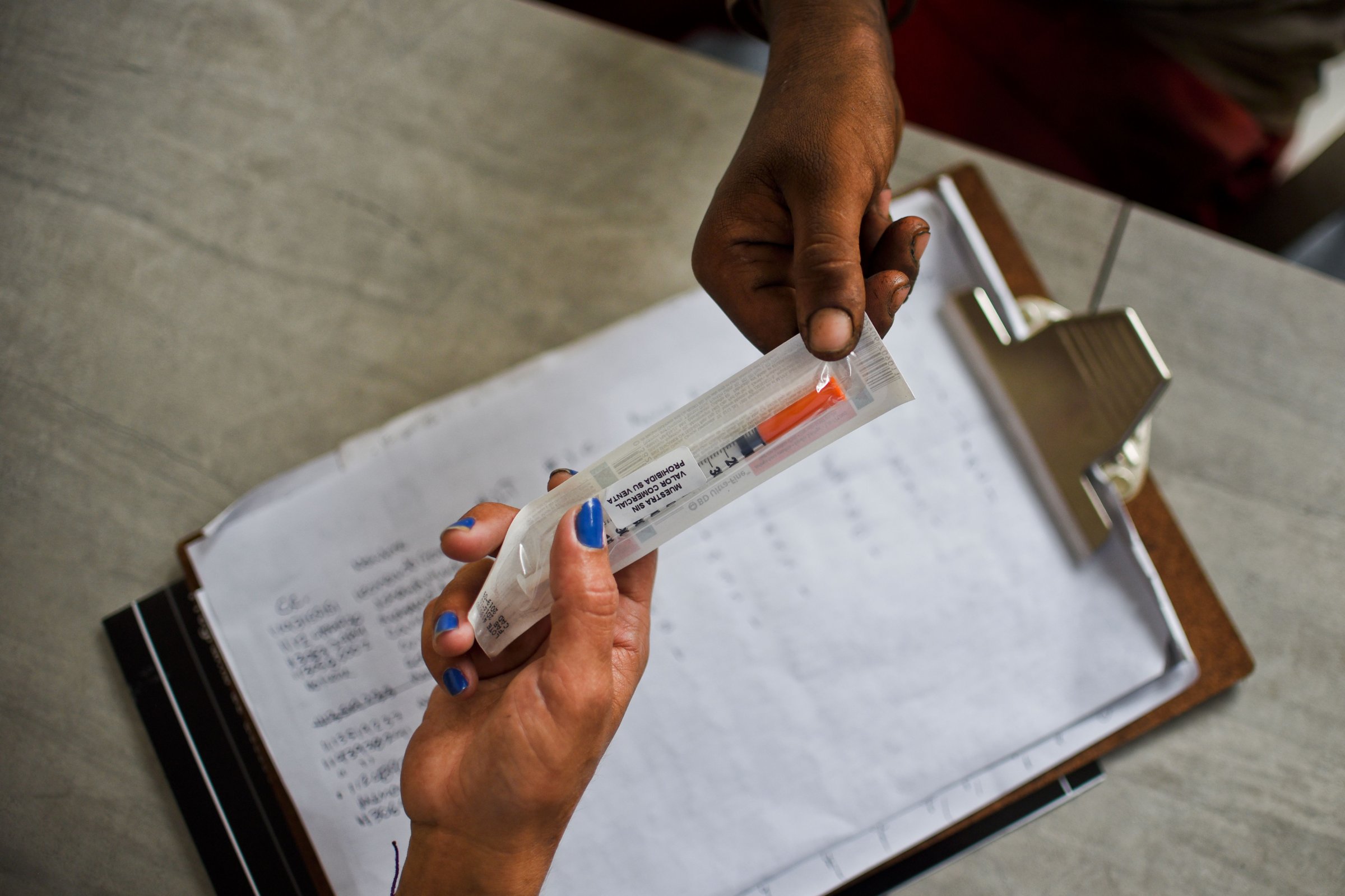

SIFs, which currently operate in Canada, Europe and Australia, offer drug users a place to use heroin and other narcotics under the supervision of medical professionals. (SIFs do not provide drugs, nor do their employees inject users directly.) Proponents say they can help curb overdose deaths, improve injection hygiene and expand access to addiction treatment. Adversaries, meanwhile, argue that they condone and enable illicit drug use.

Here’s what you need to know about the debate around SIFs.

Where are there currently SIFs?

There are approximately 100 SIFs in operation today, sprinkled across countries in North America, Europe and Australia. The first in North America opened in 2003, in Vancouver. Though no authorized SIFs currently exist in the U.S., cities including Seattle, San Francisco, Denver and Ithaca, N.Y., along with Philadelphia, are seriously considering opening such facilities. There is also an unauthorized, underground SIF operating somewhere in the U.S., according to a study published in the International Journal of Drug Policy.

Some U.S. cities, such as Boston, also operate facilities where drug users can ride out a high under medical supervision, though they cannot actively inject drugs inside. Many cities also offer needle exchanges, where users can get access to clean equipment.

Are SIFs legal?

It’s complicated.

States have the power to authorize SIFs within their borders, just as they have the power to locally legalize medical or recreational marijuana, according to an analysis published in the American Journal of Public Health.

Things get tricky, however, when looking to federal law. At least two sections of the federal Controlled Substances Act — one that bars drug possession, and one that makes it illegal to operate a facility specifically meant for drug use — could be interpreted to mean that SIFs are illegal, according to the analysis. As such, a SIF could be subject to federal legal action, even if it’s operating in a state that has authorized its existence. Still, “federal inaction would be enough to allow a state SIF to proceed,” the authors of the analysis wrote. “The attorney general could simply instruct federal law enforcement personnel to ignore the SIF, either because he or she interprets the Controlled Substances Act to allow SIFs or in the exercise of ‘prosecutorial discretion.'”

Do SIFs work?

A number of studies suggest that SIFs not only cut down on drug overdose deaths, but also reduce public drug use and improve community health by curtailing transmission of blood-borne illnesses including HIV and hepatitis C, according to a commentary published Monday in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

A 2011 paper published in the Lancet, for example, found that in the first two years after Vancouver’s SIF opened, overdose deaths in the immediate area decreased by 35%. Another paper published that year in Drug and Alcohol Dependence found that the Vancouver SIF led to significant increases in the number of people seeking methadone and other addiction treatments. Meanwhile, a 2014 review of 75 studies concluded that SIFs cut overdose deaths and improved health among drug users, without causing a concurrent increase in drug trafficking, drug use and crime in the surrounding area.

Why do people oppose SIFs?

Some opponents argue that SIFs encourage drug use — despite studies that suggest they are not correlated with any such increase — and do little to help addicts wean themselves off the habit. SIFs also give rise to a number of ethical issues. For example: Can a patient give informed consent for medical treatment if he or she is under the influence of drugs? And are doctors in conflict with the Hippocratic Oath if they allow patients to do themselves harm by injecting drugs? The dubious legality of SIFs has also raised concerns about legal and professional consequences for the doctors and nurses who would work there.

Still, while the issue is far from black and white, physician groups including the American Medical Association have come out in favor of testing pilot SIFs.

When would a SIF open in Philadelphia?

That’s still unclear. While city officials have given the green light for a facility to open in Philadelphia, they still need to find a private operator to run it. James Garrow, a spokesperson for the Philadelphia Department of Public Health, told TIME that some parties have expressed interest, but declined to name them.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that at least 63,600 drug overdoses occurred in the U.S. in 2016. About 900 of those were fatal opioid overdoses in Philadelphia, according to a report from Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney’s Task Force to Combat the Opioid Epidemic — and officials are expecting the 2017 death toll to rise.

Garrow estimated that a SIF could open within the next six to 18 months — and said city health officials are not concerned with being the first in the country.

“Our only motivation is trying to save as many lives as possible,” Garrow said.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Jamie Ducharme at jamie.ducharme@time.com