If you’ve been reading about how bad the flu is this year, it’s hard not to worry, and with good reason. The 2018 influenza season has hit hard in the U.S. and elsewhere, spreading far and wide and leading to the deaths of at least 30 children.

But when Laura Spinney hears the news about this flu season, she has an extra layer of context. Spinney’s recent book Pale Rider explores the legacy of the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, a devastating episode 100 years ago that killed perhaps as many as 100 million people across the globe.

“Although this does seem to be a particularly bad flu, it is still seasonal flu, not pandemic flu,” Spinney tells TIME, when asked what goes through her mind when she reads about this year’s flu. “At the same time, we always seem to be taken by surprise. Part of the reason for that is that we have a tendency to underestimate flu as a disease. It’s not trivial even if it is ‘just,’ in quote marks, seasonal flu.”

The distinction Spinney draws is important. By the standards of the World Health Organization, a pandemic must involve the global spread of a new disease. It is that novelty, and the corresponding lack of immunity among patients, that explains why a pandemic is more likely to make otherwise healthy people so ill. There were three known flu pandemics in the 20th century, of which 1918’s was the worst.

In contrast, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has found that this year’s seasonal flu is heavy on H3N2, a known variety of influenza A. Even though the flu vaccine is only effective against about a third of those viruses this year, seasonal variation still doesn’t mean it’s an entirely new disease. While the flu has officially reached epidemic levels in places — a standard that has to do not with novelty but with numbers — the CDC notes that such a designation is common at the height of flu season. And, while as many as 650,000 people worldwide may be killed by the flu during the annual epidemics of modern times, the estimates Spinney uses for the Spanish flu (which are higher than earlier estimates) would mean its death toll was more than 150 times greater.

The difference between then and now isn’t just pandemic versus epidemic. Nor is it solely a matter of the technological and scientific advances that came after 1918. Many people 100 years ago, as Spinney points out, lacked even the vocabulary to discuss what was happening.

Despite those differences, we can still apply lessons of the 1918 pandemic to the 2018 epidemic, Spinney says.

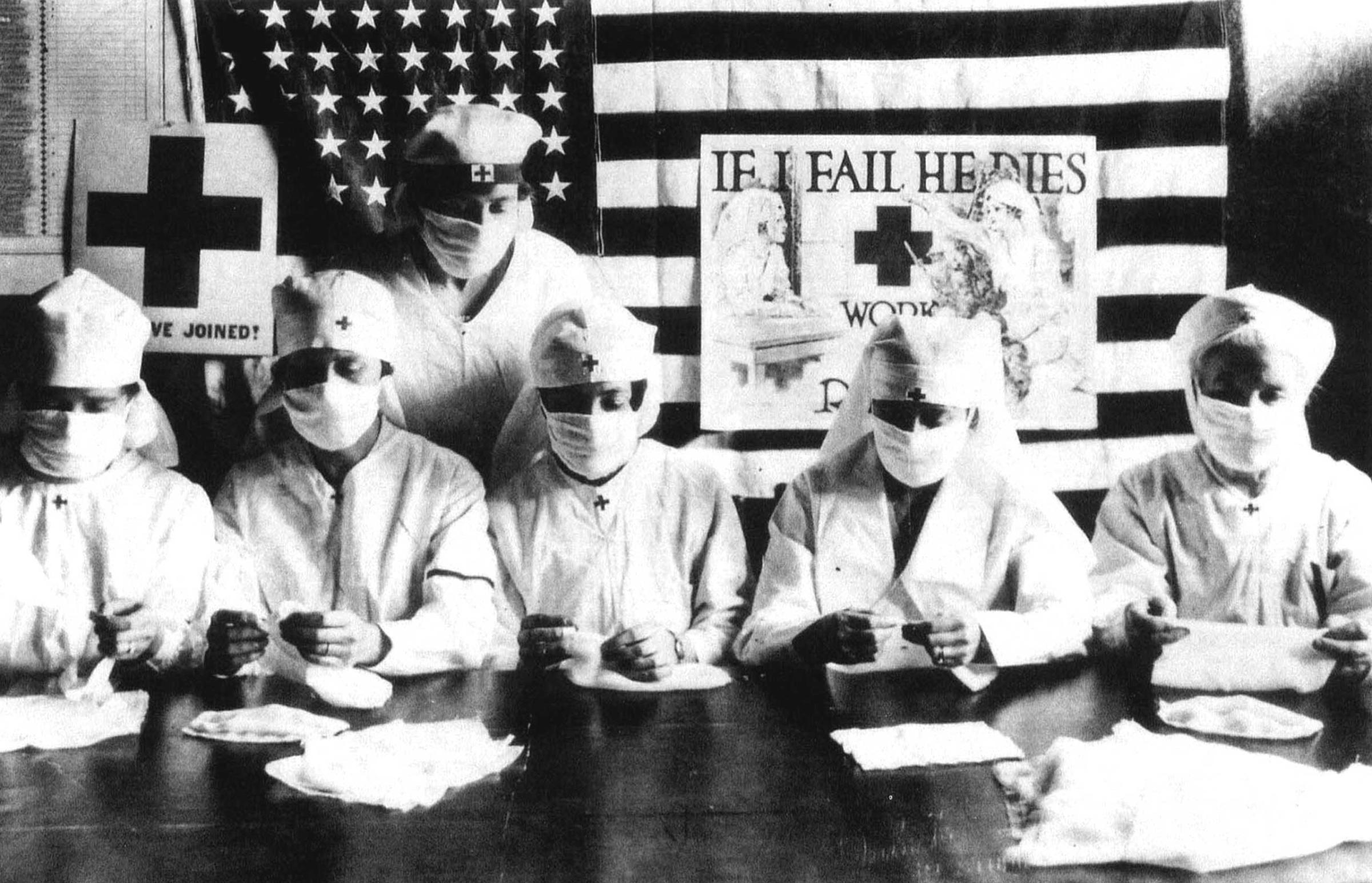

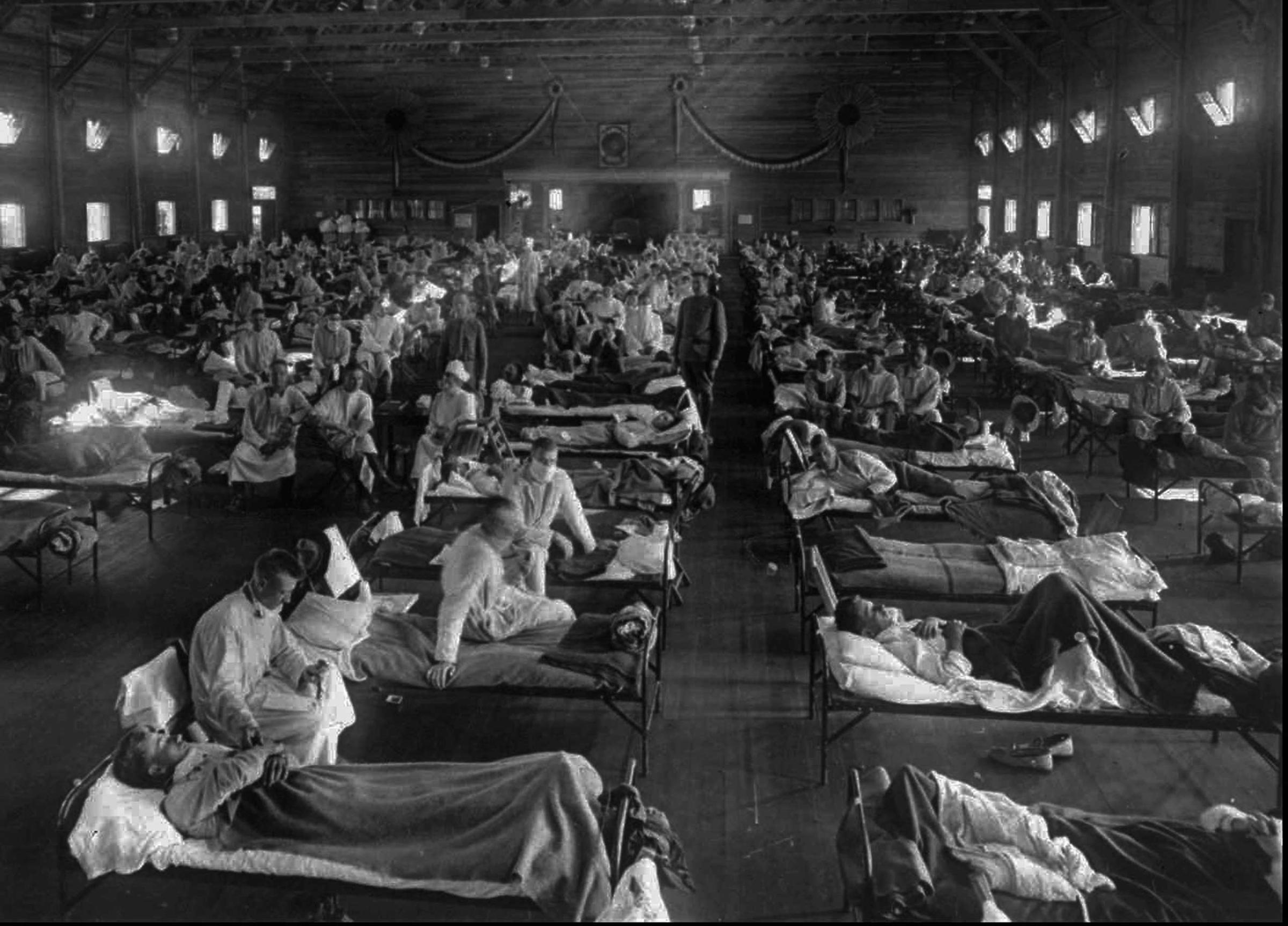

The 1918 Flu Pandemic: Scenes From a Cataclysm

One such lesson can be found in the way we see our communal responsibilities when it comes to disease prevention and treatment.

In 1918, among the many other elements of confusion about the pandemic, there was widespread misinformation about the reasons for a disease’s spread. At the time, the idea of eugenics was quite mainstream, and with it the idea that some people were genetically “better” than others. Along with that misconception came the belief that inferior people were more likely to catch and spread disease — and even that they were somehow to blame for doing so. The widespread nature of the 1918 pandemic, however, helped teach scientists and doctors that this could not be the case. After all, it felled people of all ranks of society.

The pandemic showed that, rather than looking for a eugenic solution, scientists would have to focus on the virus itself and the conditions that helped it spread. In other words, they’d have to see disease as something that happened to the community as well as to specific people.

Spinney argues that this shift in viewpoint, a process that is still ongoing to this day, could have a powerful impact on our collective ability to come to terms with a disaster such as the 1918 flu pandemic — and that it could also help us prepare for next time. After all, people who fear vaccines for the flu and other diseases, in spite of the evidence that many fears are misplaced, may say that vaccination should be an individual decision. But, as the world learned in 1918, contagious disease is never about just one person.

“Vaccination of course is a personal choice, but it’s also a civic duty,” Spinney says. “If we got into the habit of thinking that way, we’d be better armed in the case of a pandemic.”

What would happen if such a pandemic did arise? Nobody really knows for sure. Scientists and doctors are immeasurably better prepared to face a flu pandemic than they were in 1918 — but, on the other hand, the world is vastly more populous than it was back then, and that larger population is much better connected, so disease might spread much more quickly.

That’s why, faced with a fearsome flu season, Spinney turns to an old adage: forewarned is forearmed. And there are few warnings as potent as that of the Spanish flu.

“The way we remember our past and what we remember in our past, our collective past and our individual past, shapes the way we act now and our decisions in the future,” Spinney says. “We definitely won’t be ready if we don’t remember what happened then and take aboard some of the lessons.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com