One of the unspoken precepts of the presidency is that you can’t complain about the job. You are the most powerful person on earth; no one is going to feel sorry for you, whatever the challenges and pressures, whatever the abuse and frustrations and regrets.

For those like Bill Clinton, who campaigned almost from birth, there was a joy about the job even in the most brutal times, and in his final days it was hard for him to imagine giving it up. For others, like Dwight D. Eisenhower, who were more reluctant recruits, the powerful sense of duty made the Oval Office an extension of their other works, just a logical transition. For someone like George W. Bush or Barack Obama, whose paths to the Oval Office were relatively short–a detour in a life headed elsewhere–they did the job, all in, and then left it behind.

With Donald Trump, the nation is seeing something new. Although he flirted with running as an independent decades ago, and as a Republican in 2012, he was never driven by a vision, an agenda or a set of goals. He gave every indication of wanting to win the presidency but not be the President.

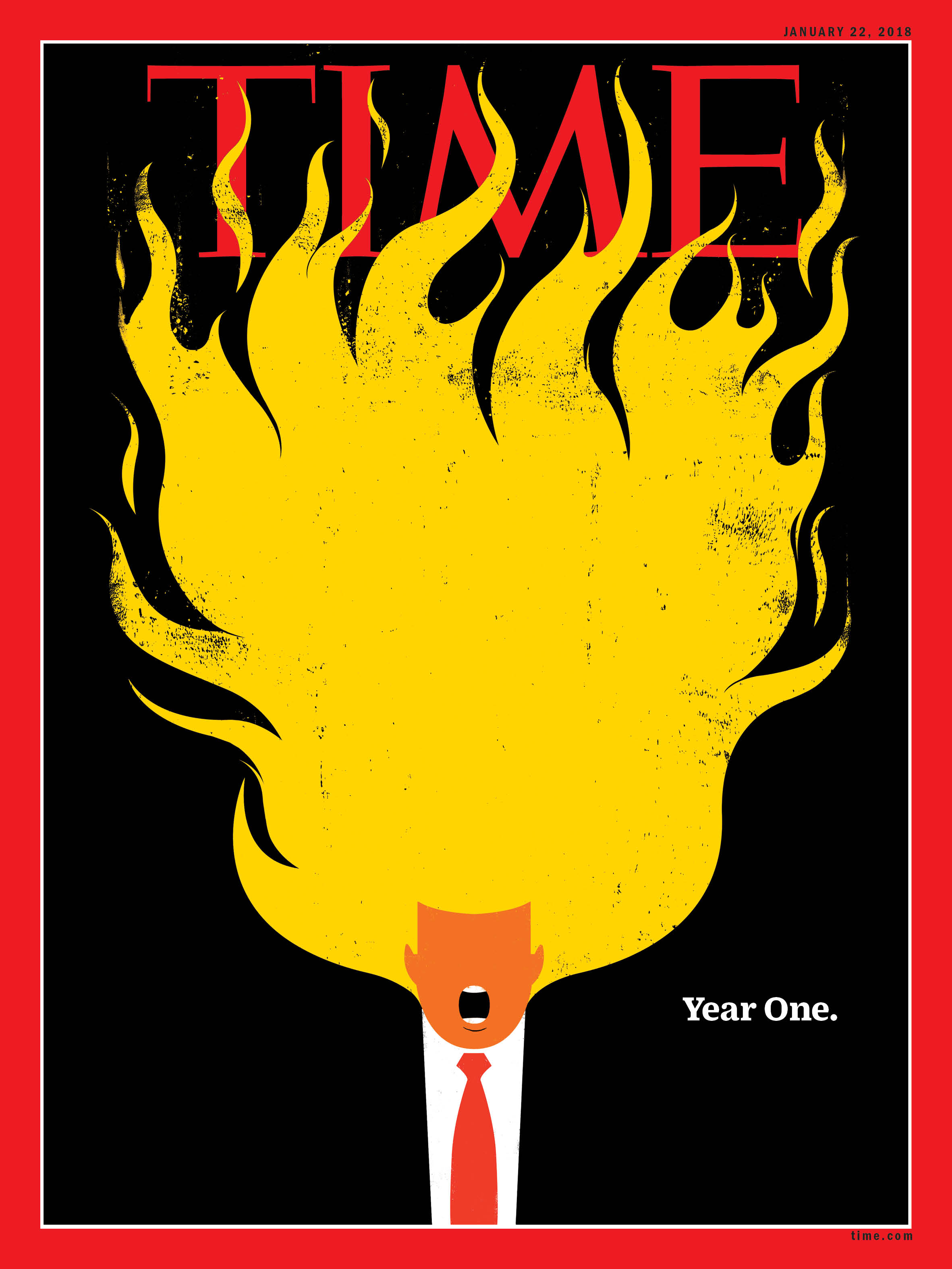

That impression, and so much more, is brought to life in Michael Wolff’s explosive and controversial new book, Fire and Fury, a damning account of the first nine months of the Trump presidency that has Democrats salivating and studying the Constitution and Republicans fretting over its conclusions while pretending to criticize it as a hatchet job. The President was so incensed by the book and its many criticisms of his leadership style that he tried to block its publication even after Fire and Fury was widely available, thereby guaranteeing that it would sell out everywhere from Maine to Montana. So many are the questions raised in the book about his suitability for office that Trump was left to declare in a Jan. 6 tweet that he is a “very stable genius.”

For all the criticism of Wolff’s methods, much about the portrait rings true. Trump didn’t expect to win and, if he thought about it, probably didn’t want to. The campaign itself gave him the power and the glory and the profits. The office takes those away. In the terms he cares about–nuclear button notwithstanding–he is in many ways less powerful as President than he was a year ago. Candidates can say whatever they want about what they will do; Presidents are expected go out and do it. There’s more ridicule and much less freedom. Harry Truman’s “great white jail” is spartan compared with a life pinballing between Mar-a-Lago and Fifth Avenue. The rewards of the office, such as they are, aren’t rewarding to Trump, other than the pomp, the crowds, the chance to show off the Lincoln Bedroom or to see in our response an awe he does not share but likes provoking. The fuel that powers the presidency–the passion for ideas, the attachment to allies, the give and take of practical politics–gives him no energy. So this is an exhausting, even debilitating, life for a 71-year-old, much less one with little curiosity or sense of mission beyond self-interest. The most thin-skinned public figure imaginable has been exposed to the elements. And he doesn’t like them.

All of this speaks to fitness, which is different than mental capacity or competence or proficiency with policy. It goes to wanting to learn, to grow into the role, to be tested by the office held by others in more difficult times, to make the best of the challenge history hands you. As portrayed in Fire and Fury, Trump is little interested in such things. He is a President who is almost annoyed by the office he holds. What an unhappy man he must be.

As is so often the case with Trump, the portrait painted is shocking but not surprising. Wolff is known for his bare-knuckled prose, his flexibility with facts, his instinct to capture larger truths, to see the forest without being able to name every tree. And so this President, this White House, was his perfect subject. Trump is the same man America watched through the campaign, breaking rules, flouting convention, surrounded by amateurs, doing sometimes-brilliant improv, nothing planned or plotted. Is he the least calculating, most instinctual President this country has ever seen? Thanks to his Twitter feed, he is certainly the most transparent one; the tantrums aren’t hidden, nor the insecurities, nor the knowledge gaps, grievances, blind spots, tone deafness. None of this has been secret. Majorities of Americans disapprove, just as majorities did before he was elected.

So what changed? Mainly it is that Wolff’s book captures the President’s own advisers admitting what so many people have been seeing, after a year spent denying that water is wet. Again and again this President and this White House asserted things that were flatly untrue: the numbers, the crowds, the votes, the size of the tax cuts. We’re no longer through the looking glass. That has implications for everything.

Books about sitting Presidents are extremely hard to do well. They are particularly hard to do about a President who has such a broad definition of truth, much less one who said, according to Wolff, “I’ve made stuff up forever and they always print it.” Clarity is elusive on a good day. Longtime White House reporters will tell you that there are as many opinions about what happened at a West Wing meeting as there are people in the room.

Wolff’s technique isn’t to air all sides. In Fire and Fury he most often presents a version of the truth that comes straight from the mouth or memory of Trump’s now defenestrated adviser Stephen Bannon, the right-wing warrior who joined Trump’s team in August 2016 and lent it so much of its raw cultural power in the closing days of the campaign. Bannon then went to Washington with the President-elect to advance the chief strategist’s anti-immigration, anti-corporate, nationalist agenda, whether or not Trump fully agreed with it. Fire and Fury is the story of his triumphs and failures before he flamed out seven months in.

Wolff’s book confirms what others have glimpsed or reported about the baroque character of the Trump White House. But it does so in detail so granular that it may become, even with its shortcomings, a definitive text on the 45th presidency. Some elements are beyond question. The Trump White House, within days of the Inauguration, was split into three endlessly warring camps: the neopopulist wing under Bannon; the GOP establishment wing under chief of staff Reince Priebus; and the Democratic-leaning Manhattan wing under Jared Kushner and Ivanka Trump. The three factions leaked and counterleaked against one another to gain the upper hand or the President’s favor, or both. (While Bannon and Kushner were famously unavailable for on-the-record interviews, both became, as Wolff notes, “the background voices to virtually all media coverage of the White House.”) Trump signed Executive Orders favoring one faction or another, often without the other camps’ knowledge, which led to more heartburn and retribution.

And yet for most of the nine months of 2017 covered by Wolff’s book, Trump never settled in any one camp. Instead, the President spent hours complaining about his aides, family members and various advisers, detailing their weaknesses, humiliating them in meetings, making sure no single person accumulated too much power. “We serve at the President’s displeasure,” said one. Although he had somehow won the White House and therefore must be a man of protean ability, evidence was hard to find: many aides found him incurious and even hostile to information; he didn’t read (“he didn’t really even skim,” Wolff writes), devoting himself to headlines but little else. He was not a good listener and tended to ignore people who imposed on his time. He resisted opinions by anyone labeled an “expert” and dismissed as “geniuses” people who acted mentally superior to him. Wolff reports that he was “almost phobic about having formal demands on his attention.”

He could be, moreover, hesitant and uncertain about how to react to problems, so aides found ways to work around him, to “game him” into action. For example, Dina Powell of the National Security Council learned from Ivanka that photographs and charts could move him on foreign-policy questions. When she wanted Trump to respond to Syria’s use of chemical weapons, she showed him a presentation with photographs of children injured in the attack. The President decided to retaliate by firing Tomahawk missiles at a Syrian military base.

Other details of Trump’s leadership style are interesting if not downright curious. He uses people’s appearances as a gauge of whether they can succeed. (He is sensitive about his own image too: when a news report portrayed him in February 2017 as roaming the White House late at night in his bathrobe, he railed against the portrayal.) Wolff reports that Trump, at least early on, repaired to his bed many nights, often as early as 6:30 p.m., with a cheeseburger nearby, to watch TV and make phone calls to friends, seeking advice. (Aides often spent time the next morning trying to talk the President out of acting on the nighttime suggestions.) Although Trump can be coarse and flamboyantly sexist in his references to women, he seems more comfortable taking advice from women than from men.

As lurid as Wolff’s portrait of Trump may be, the President’s chief strategist is the book’s central character. Bannon emerges as a man at odds with himself: thrilled to be leading a populist revolution from the seat of American government, but deeply conflicted about playing any part in the power structure. This leads him down bad alleys, such as taking on the President’s family. The book pulls back the thick, brocaded curtain shrouding Ivanka Trump and Jared Kushner, the two family members with official White House jobs who have a hand in a wide array of policy matters and a say in virtually everything else. Bannon identified “Jarvanka” early on as his chief rival, not only because of the couple’s blood proximity to the President but because their politics were marginally left of center (and decidedly left of Bannon’s). It was Jarvanka who worked to keep Kellyanne “Alternative Facts” Conway off the TV; who insisted the 2017 State of the Union speech sound moderate and evenhanded; and who pressed Trump to bring in Anthony Scaramucci to run communications for 10 disastrous days last summer. The infighting between the camps is particularly brutal; in many ways the book is more Bannon’s withering indictment of Jared and Ivanka than of the President.

Bannon isn’t content to oppose Jarvanka; he wants, at least in Wolff’s rendering, to destroy them. When Bannon convinces Trump to withdraw from the Paris Agreement to curb climate change, he says, “The bitch is dead.” And when Trump fires FBI Director James Comey in May, Bannon fingers Jared and Ivanka as the triggermen, in part because he believes that single decision sparked a chain of events that could ruin the President. “The daughter,” Bannon said, “will take down the father.” According to Wolff, Bannon thinks that Jared and Ivanka advocated for firing Comey because their own global business interests might not stand up to federal scrutiny. Some of this fear, Wolff asserts, stemmed from the fact that Jared’s father Charles was concerned that his own family’s finances would become entangled in the Trump probe. “Ivanka is terrified,” Bannon told Wolff.

By midsummer 2017, Bannon is fully at war with Jared and Ivanka, impatient with their ideas, resentful of their clout, jealous of their media savvy and working nonstop to undercut their reach. Indeed, the strangest passage in the book comes in the penultimate chapter, when Wolff lets Bannon go on a delicious-if-true, 2,000-word rant about the risks posed to the family and its business interests by the Russia probe. It is late July now, and Bannon is on the outs with the Trumps, feeling outnumbered and unloved, surrounded by his self-made enemies and, at least in private, lashing out in many directions. Bannon had spent some time, according to Wolff, trying to get the Trumps to create a special SWAT team of lawyers and spin doctors to handle special counsel Robert Mueller’s probe, much as Bill Clinton did in 1998 to counter the investigation of independent counsel Kenneth Starr. The best defense, Bannon believed, is a better offense. Trump would just have to gut it out.

But that plan never got off the ground. Which explains in part why Bannon was dumbfounded by a July interview Trump did with the New York Times, in which he somewhat inexplicably warned Mueller to stay away from his family’s finances. “‘Ehhhh … ehhh … ehhh,’ screeched Bannon, making the sound of an emergency alarm. ‘Don’t look here! Let’s tell a prosecutor what not to look at!'”

Bannon then notes that Mueller had hired one of nation’s top money-laundering prosecutors to dive into the deeply complicated financial transactions that make up the Trump real estate empire. He asserts that Mueller will also biopsy the deals made by Kushner, just as his father had warned. “You realize where this is going,” Bannon continued. “This is all about money laundering. Their path to f-cking Trump goes right through Paul Manafort, Don Jr. and Jared Kushner … it goes through Deutsche Bank and all the Kushner sh-t. They’re going to roll those two guys up and say, Play me or trade me.”

Then Wolff writes, “An expressive man, Bannon seemed to have suddenly exhausted himself. After a pause, he added wearily: ‘They’re sitting on a beach trying to stop a Category Five.'”

Left unexplained is how, much less for whom, money might have been laundered. It is a real weakness of Fire and Fury that Wolff permits Bannon to go on without providing any evidence for such claims. Readers have poked holes in some of Wolff’s facts and sources have disputed quotes attributed to them. It’s not the first time in his career that the author’s accuracy has been challenged.

But then maybe it takes a thief to catch a thief. Some argue that with a President like Trump, the normal rules of journalism don’t apply. By this logic, a President who has such a casual relationship with the truth requires loosening the rules about cross-checking claims with all sides, supplying evidence for sweeping observations and providing the source of every quote and detail. Whatever questions linger about Wolff’s methods, the central narrative of Fire and Fury may take years to prove. In the meantime, the book will confirm what both sides already believe: Democrats will see in it explicit conformation of all that is unfit and unworthy in Trump, while Republicans will see instead all that is wrong with the news media.

Yes, the book has broadened a conversation taking place in Washington (again, mostly among hopeful Democrats) about whether we are approaching a moment when members of Trump’s Cabinet somehow get together and invoke the 25th Amendment, which has a long-ignored passage about how an Administration can replace a Commander in Chief when his faculties are impaired. This is little more than a liberal fantasy. Presidents don’t get replaced by their subordinates. They get impeached by their opponents. So far, about once a century.

Instead, the consequences of the book may be borne by Bannon. All the incendiary claims and quotes he coughed up to kneecap Ivanka and Jared now read like a political suicide note, and his attempts to walk them back did little good. First the right-wing media impresario lost the backing of his financial patrons, hedge-fund mogul Robert Mercer and his daughter Rebekah. Then, on Jan. 9, he was drummed out of his role as the boss of Breitbart News, the perch from which he planned to wage war on the GOP establishment. “Sloppy Steve,” Trump’s new sobriquet for Bannon, will stick to him for a while.

As for Trump, there is no sign that this book will change him at all, though he is clearly obsessed with its details and conclusions. (Perhaps to rebut the charges about his mental acuity, Trump took the extraordinary step on Jan. 9 of admitting cameras into bipartisan immigration negotiations for 55 minutes.) Axios reports that his official day now starts at 11 a.m., with the bulk of the morning carved out for “executive time”–watching TV, tweeting and talking to friends. He’s spent one day out of three in his presidency so far at one of his ritzy properties; having ridiculed Obama for his time on the links, Trump played golf, by one count, 75 times in 2017. That means he golfed, on average, more than six times a month, which would count as a lot even if he were a nice Florida retiree. Which he isn’t.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com