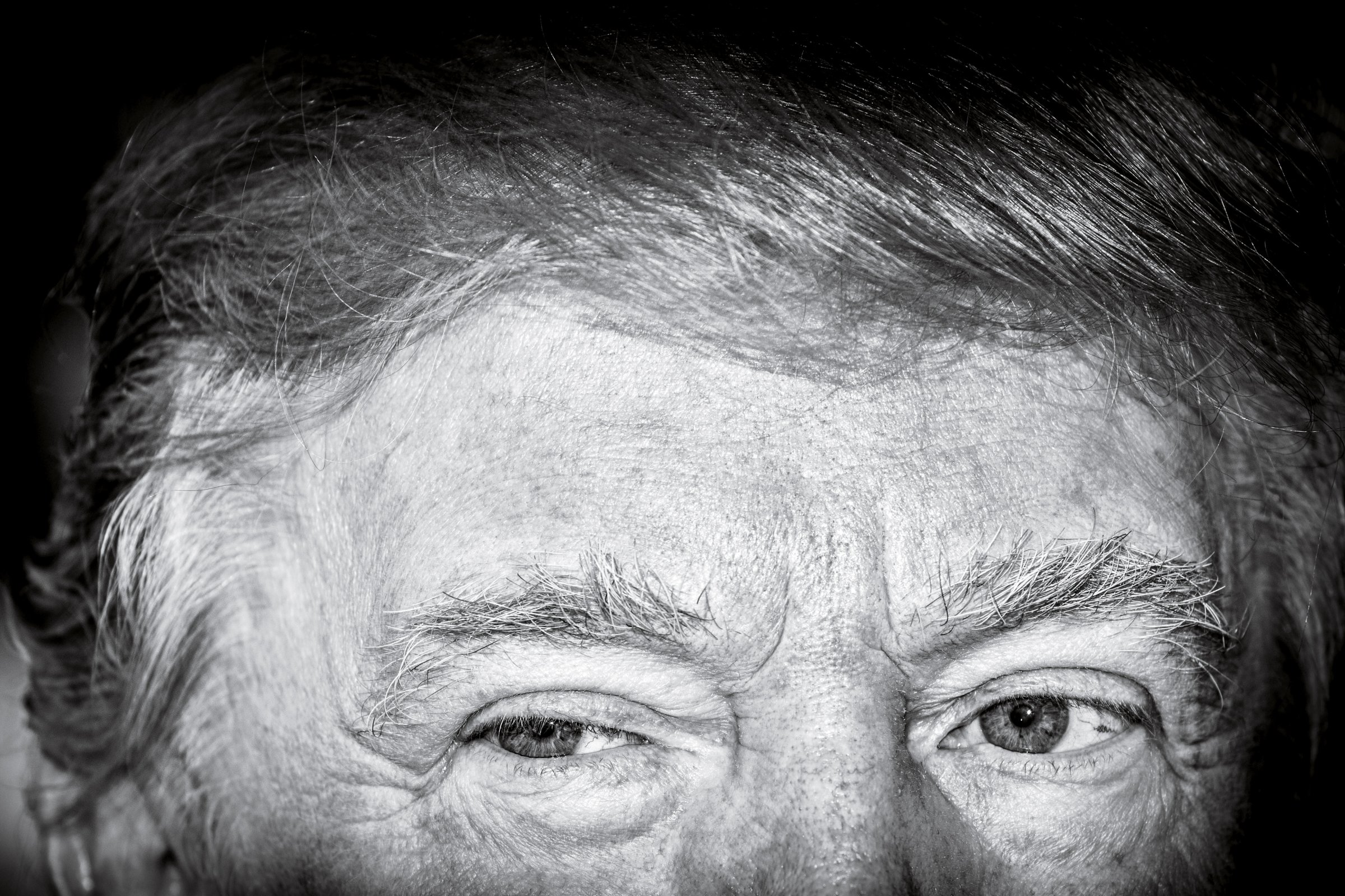

It was bitterly cold as Donald Trump sat down to dinner on Jan. 5 at Camp David, the presidential retreat in Maryland’s Catoctin Mountains. Republican leaders and Administration officials had joined him for what needed to be a frank conversation. Mitch McConnell, the Senate majority leader, sat to Trump’s left; Paul Ryan, the House Speaker, to his right. The group had planned to take stock of their first year in power and hash out strategies for the next. But try as they might, Ryan and McConnell struggled to get the President to focus.

Trump had something else on his mind: a gossipy, unflattering new book, Fire and Fury, that was consuming Washington’s chattering class. The President seethed at the disloyalty of his former counselor Stephen Bannon; he raged about the book’s author, Michael Wolff. Guests gently tried to bring the President back to the topics at hand: a packed congressional to-do list, the looming midterm elections and the many potholes in their path. But Trump kept fuming, his arms crossed. At least it’s not the Russia investigation this time, McConnell and Ryan thought, according to aides. As both men later told allies, they should know better at this point than to be surprised.

The evening illustrated the accommodation the President and his party have reached one year into their marriage of necessity: Trump will do what Trump will do, and the Republican Congress will try to mind its own store. The partnership hasn’t been easy, but it has, for both sides, been fruitful. For all of Trump’s impulsive behavior, Republicans wrung much that they wanted out of 2017. The passage of the tax bill in December was the first time Congress had delivered on such a thorny issue since Ryan was slinging McDonald’s hamburgers as a Wisconsin teenager. Trump appointed a conservative to the Supreme Court and many more to the federal judiciary, while rolling back scores of regulations. In exchange for putting up with Trump’s chaos, lawmakers got a respectable list of policy wins in the traditional GOP mold. It was, McConnell said at Camp David, “the most consequential year” of his more than three decades in Washington.

For his part, Trump got the big victories he wanted. He’s been able to claim credit for the stock market, which is soaring, and the unemployment rate, which is at its lowest point in years, while offloading the hard (and, to his mind, dreary) work of devising policy to his eager partners on the Hill.

But now what? The one-year mark of a presidential Administration is often a high point, and Republicans worry that it’s all downhill from here. There’s little hope for any major legislation in 2018. The political climate is dire and getting worse. And there are challenges looming that they cannot control: the provocations of North Korea, the investigation into Russia’s meddling in the 2016 campaign, the threat of terrorism.

At Camp David, the legislators tried to impress these realities upon Trump. “Last year would be a tough year to top,” McConnell said. Trump paid little heed, repeatedly interrupting meetings with his rolling rant. On Jan. 6, the lawmakers woke to a series of tweets in which the President proclaimed himself “a very stable genius.” Over breakfast, the lawmakers groused to each other. This again. They couldn’t help but note with some glum humor that just the night before, the White House had treated them to a movie: The Greatest Showman, a new musical about the life of P.T. Barnum, a man whose skill at shocking, entertaining and fooling the public never earned him the respect he felt he deserved. The President, aides said, quite enjoyed it.

Like many forced marriages, the partnership began with unrealistic expectations and mutual misunderstanding. Republicans, divided for years between a status quo establishment and a rabble-rousing right wing, tried to convince themselves that Trump just might be the unifying figure they needed. With his force of personality and self-proclaimed dealmaking prowess, maybe the new President could finally get the moderates and the right-wing Freedom Caucus to row in the same direction.

Trump, meanwhile, figured the professional politicians knew their jobs. After all, the GOP had spent seven years promising to get rid of Obamacare and replace it with something better. Now they had the power to do it. Trump was surprised when it turned out they had no idea how. The President is an older man, set in his ways, but members of Congress hoped the gravity of his role and the experienced aides surrounding him would bring him around to the normal procedures.

Then, just a week after the Inauguration, came the travel ban.

“Blindsided? It was like a crowbar to the bridge of the nose,” says Republican Representative Charlie Dent, a Pennsylvania moderate who’s among 37 House Republicans not running for re-election in their districts in this sour season. Dent found out about the ban when his son texted him that a local family of legal Syrian immigrants had had their visas revoked in midair. “It was a fiasco,” Dent recalled. “I called the White House and said, ‘What’s going on?’ It took about five minutes to understand that they didn’t run it by the Department of Defense, or State, or Homeland Security, or Justice. He just signed the Executive Order and sent out a press release.” Dent spent the next 10 days helping get the Syrian family readmitted.

It was a sign of things to come. Trump would do things differently and quickly, and he was not necessarily planning to keep his would-be allies in Congress in the loop. Those around him weren’t as sage as they were cast; the Speaker’s office became a Government 101 tutorial for senior officials baffled by the basics of how a bill becomes a law, let alone arcane minutiae. Time and again, Republicans were asked to answer for another presidential statement they couldn’t explain and didn’t, in many cases, care to defend.

In March, the GOP’s first stab at Obamacare reform failed. But in April, Neil Gorsuch was confirmed to the Supreme Court, shepherded by McConnell and his allies. (The process was norm-shattering in its own way: McConnell refused to consider a nominee for a year until a Republican President could fill the seat, then eliminated the 60-vote threshold to get Gorsuch through.) Congressional leaders held the episode up to Trump as a case study: See how we can both win if you just help us help you?

But any hope that normalcy might reign was dashed in May, when Trump abruptly fired FBI Director James Comey, offering a jumble of explanations, none of which made the GOP comfortable. In July, Obamacare repeal failed, twice more, to make it through the Senate. In August, Trump waffled on forcefully condemning the violent white nationalists who’d killed a woman in Charlottesville, Va. In September, after months of nationwide protests, came the final failure of Obamacare repeal.

Three weeks after the health care bill’s demise, members of Congress went home to an irate base and demoralized donors. The National Republican Senatorial Committee lost several million in pledges in the wake of the failure. That, according to a chief of staff to a House Republican, was the “holy sh-t moment” when lawmakers realized they were going to have to get something done. Outside groups warned of trouble ahead. “Voters demand results. We have to deliver,” says Corry Bliss, a GOP strategist running a Ryan-backed super PAC with plans to spend $100 million defending House Republicans in 2018. “In American politics, you’re graded on a two-year scorecard.”

Republicans came to grasp that Trump was never going to lead in a focused, traditional way. If Congress was going to get anything done, they were going to have to do it on their own. “The whole ‘give him some runway, cut him some slack’ argument–I haven’t heard that stuff for a while,” the House GOP staffer says.

The failure of the health care push also sobered Trump, allies say. It taught him that he couldn’t trust or bully Congress to deliver on its promises either. And while the ultimate victory on tax reform was a major win for both sides, the lack of meaningful cooperation on its passage only underscored the fundamental dysfunction of the relationship. “Here’s the ultimate issue,” says former Trump adviser Sam Nunberg. “He doesn’t like these guys or respect these guys. He thinks they’re all losers. By the way, they are all losers. But he needs them. He knows that.”

The strains in the relationship are easy to spot. Trump and McConnell went weeks this summer without as much as a word between them. GOP gatherings with the President now often have the air of a corporate retreat with a CEO no one really likes. During the Camp David sessions, Trump attended every roundtable and often touted the success of his team. “Isn’t he tremendous?” Trump would ask those assembled in the wood-paneled conference rooms as a new official was called on to speak. Congressional leaders have come to expect these fawning ceremonies. They believe Trump’s need for affirmation is one reason he spends so much of his day watching supportive television hosts and calling friends outside government. Ryan and McConnell lead the chorus when they’re summoned but privately dislike the show.

But these days members can’t always mask their frustration. During an unexpected press conference at Camp David, Trump ordered his guests to line up behind him. The No. 2 Republican in the House, Kevin McCarthy of California, gulped down a giggle and shifted his weight as Trump boasted about attending the finest college. When the President suggested it should be easier to sue journalists for libel, McCarthy closed his eyes. By the time Trump was mocking “Sloppy Steve” Bannon, McCarthy was openly laughing.

Just 48 hours after the Republicans returned from Camp David, Trump gathered lawmakers from both parties in the Cabinet Room for a discussion about immigration. For 55 minutes, with cameras rolling, the President considered the future of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, an Obama-era executive action shielding from deportation hundreds of thousands of young immigrants brought to the U.S. illegally. Trump had ordered it to end, but to the astonishment of the Republicans, Trump now said he was game to preserve it–even as members of his party tried to steer him away from that inclination. “It should be a bill of love,” the President said, adding that he’d love to see a comprehensive immigration overhaul. “If you want to take it that further step,” Trump added later. “I’ll take the heat.”

It was a reminder of how difficult legislating will continue to be with a perpetually unpredictable President. The White House walked Trump’s comments back; by the evening, Trump was on Twitter, demanding a border wall that Democrats don’t support. The zigzag was maddening to Republicans, but not surprising. This is the bed the GOP has made, and it is too late to climb out of it.

The Republicans excused Trump’s antics during the campaign with the justification that he was better than Hillary Clinton. In office, they rationalize that he has given them generational victories on judges and taxes and has energized voters and brought new ones into the mix. Once-forceful critics have found reasons to work with Trump. “I said he was a xenophobic, race-baiting religious bigot,” said Senator Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, one of Trump’s 2016 rivals who came up short. “He won. Guess what? He’s our President.” Graham is now a golf partner.

But Republicans also are keenly aware that they may pay the price for the partnership in November. Historically the party in the White House suffers deep losses during a President’s first midterm elections. Republicans have a 24-seat cushion in the House and a skimpy one-seat edge in the upper chamber. A CNN poll in December found just 38% of voters likely to vote for Republicans in Congress in 2018; independent voters favored Democrats by a 16-point margin.

If the President is worried by this, he’s making no public show of it. Trump wants to campaign for Republicans and boasts about the crowds he draws, but it’s not clear many of the candidates will welcome him. In fact, some White House advisers see Vice President Mike Pence as the more useful figure in turning out conservative voters this year and are fielding requests for Ivanka Trump to win over independents and women. Many Republican candidates are likely to do in November what their leaders in Congress did not: keep their distance. A year after Inauguration Day, one can only imagine what the second anniversary will look like.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Molly Ball at molly.ball@time.com and Philip Elliott at philip.elliott@time.com