He couldn’t have put it more plainly. On April 13, 1965, in the midst of a congressional debate over the proposed 25th Amendment to the Constitution dealing with presidential succession and incapacity, the chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, Representative Emanuel Celler of New York, dispensed with high-minded legal arguments. They were there, Celler said, to figure out what might be done if the unthinkable–a deranged American President with nuclear weapons–became thinkable. “The President may be as nutty as a fruitcake,” Celler declared on the House floor. “He may be utterly insane.” And for this reason, America needed a plan.

Ratified two years later, the amendment offered the country just that. And now, half a century on, the subject of whether President Donald Trump could face a removal from power under its terms is one of an ever widening conversation. “The 25th Amendment is a concept that is alive every day in the White House,” said Michael Wolff, author of Fire and Fury: Inside the Trump White House, on NBC’s Meet the Press. White House officials have strongly denied this–but, as ever, the President himself has managed to keep the issue alive by tweeting about his mental stability.

Is the 25th Amendment chatter simply a liberal fantasy? A #resistance fever dream? Political porn for wonks? Almost certainly, but we live in a world in which the outlandish (a President Trump) became a reality, so who’s to say where our political melodrama will end? It’s highly unlikely, but this unprecedented presidency could lead to unprecedented constitutional ground: the invocation of the boring-sounding yet world-shaking Section 4 of the 25th Amendment–a provision that enables the Vice President, with a majority of members of the Cabinet, to declare the President unable to discharge his duties, thus installing the Vice President as acting President pending a presidential appeal to, and vote by, the Congress.

We know, we know: it all sounds overheated, particularly when you consider that Vice President Mike Pence is one of Trump’s chief enablers and that the Cabinet officers all owe their place to Trump, whom they would be voting to humiliate. And yet the mechanics are in place, and the history of the question of presidential incapacity, and of the amendment itself, shows that lawmakers at midcentury anticipated a President whose instability might amount to disability. So why pass up a teachable moment to explore remote constitutional hypotheticals?

Personal and abstract forces shaped the debate over the capacity sections of the 25th Amendment. There were memories of Woodrow Wilson’s long convalescence from his October 1919 stroke; the evident (if rarely acknowledged in real time) illness and wartime death of Franklin D. Roosevelt; Dwight D. Eisenhower’s heart attack in 1955 and stroke in ’57; and John F. Kennedy’s assassination in 1963. The advent of the Cold War, meanwhile, had sharpened the question of a President’s capacity to respond instantly to an existential nuclear crisis.

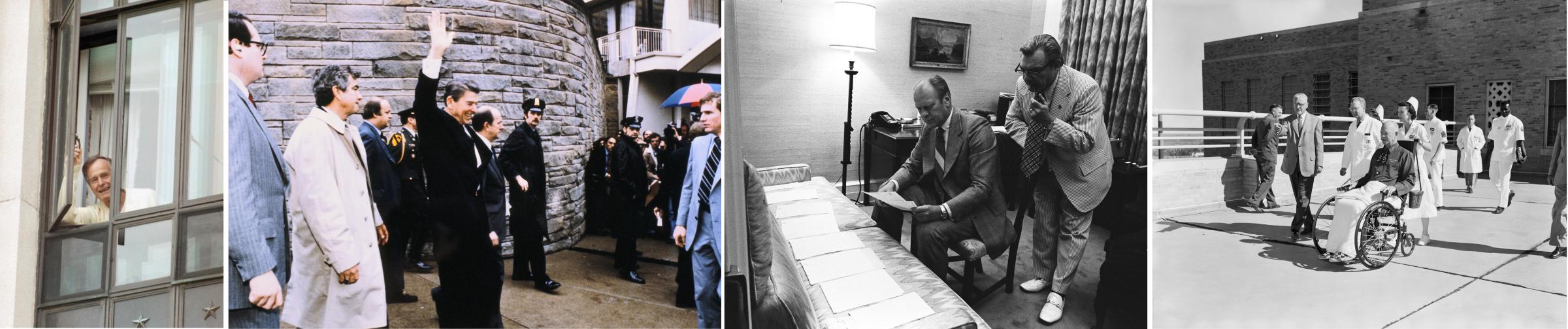

The 25th Amendment has four sections, three of which have to do with presidential succession and the filling of the vice presidency in the event of a death or resignation. Section 3, under which a President can temporarily transfer authority if he, for instance, undergoes surgery, was invoked by Ronald Reagan in 1985 and by George W. Bush in 2002 and ’07. George H.W. Bush, who suffered from a thyroid condition, was ready to invoke Section 3, giving Vice President Dan Quayle temporary power if he was seriously felled by illness, but it never came to that.

Section 4 is where things really get interesting. That provision, wrote John D. Feerick, a legal scholar and a key architect of the amendment, “covers the most difficult cases of inability–when the President cannot or refuses to declare his own inability.” The modern framers contemplated nightmare scenarios as they drafted the amendment, including, Feerick recalled, “situations where the President might be kidnapped or captured, under an oxygen tent at the time of enemy attack, or bereft of speech or sight.” One Section 4 scenario: an emergency medical situation during which the President was unconscious or disabled for a period of time (a coma, for instance). It was clear from the debates at the time of adoption and ratification, according to Feerick, that “unpopularity, incompetence, impeachable conduct, poor judgment and laziness do not constitute an ‘inability’ within the meaning of the amendment.”

The drafters took pains to make clear that this was not an option to be taken in ordinary times. “We are not getting into a position,” Indiana Senator Birch Bayh, the amendment’s chief author, said in response to questions from Senator Robert Kennedy of New York, “in which, when a President makes an unpopular decision, he would immediately be rendered unable to perform the duties of his office.” The position they were getting into was more apocalyptic. “It is conceivable,” Bayh said, “that a President might be able to walk, for example, and thus, by the definition of some people, might be physically able, but at the same time he might not possess the mental capacity to make a decision and perform the powers and duties of his office.”

The most contentious issue, then, would be psychological ability, not physical. And the context would likely be some kind of standoff in which a President, in the overwhelming opinion of one elected official (the Vice President) and of officials confirmed by the Senate (a majority of the Cabinet), appeared unfit to execute his duties. There is also language in the amendment that allows a majority of “such other body as Congress may by law provide”–perhaps a panel of medical experts (or even Congress itself)–to weigh in. In 1965, Representative Richard H. Poff of Virginia said Section 4 was designed to meet a moment “when the President, by reason of mental debility, is unable or unwilling to make any rational decision, including particularly the decision to stand aside.”

After his stroke early in his second term, Eisenhower drafted an understanding with Vice President Richard Nixon that authorized him to step in for a time if Eisenhower were incapacitated. There was, however, a possibly fatal flaw in Ike’s plan: “The President,” Eisenhower wrote, “would determine when the inability had ended and at that time would resume the full exercise of the power and duties of the Office.”

But what if the incapacity had not, in fact, been overcome? What if the President believed himself to be fit but was not? This was the issue the drafters wrestled with in Section 4. Like Eisenhower’s informal plan, Section 3 handled situations like convalescence from physical problems. The questions for Section 4 involved trickier scenarios in which the President suffered, for instance, from some kind of mental-health issue that he might not recognize but others around him did. “I admit this: if a man were so deranged that he thought he was able, and the consensus was that he [wasn’t],” Eisenhower said, “there would have to be something else done.”

Section 4 of the 25th Amendment was that something else. In such a case, according to the amendment, the Vice President and a majority of the Cabinet, or Congress’s “such other body,” could sign a letter to the Speaker of the House (Paul Ryan) and the president pro tempore of the Senate (Orrin Hatch) declaring the President unable to discharge the office. If this happens, the Vice President becomes acting President. If the President in question disagrees about his incapacity, he can, in writing, challenge the invocation of Section 4. In this constitutional tennis match, the Vice President, who remains acting President, and the Cabinet majority then have four days to decide whether to reassert the claim of incapacity. If they do so, Congress then takes up the matter. As the amendment states: “Thereupon Congress shall decide the issue, assembling within forty-eight hours for that purpose if not in session. If the Congress, within twenty-one days after receipt of the latter written declaration, or, if Congress is not in session, within twenty-one days after Congress is required to assemble, determines by two-thirds vote of both Houses that the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office, the Vice President shall continue to discharge the same as Acting President; otherwise, the President shall resume the powers and duties of his office.”

If the issue were allegations about a President’s mental health–the likeliest scenario–Congress could presumably investigate, impaneling doctors and taking testimony. And there’s this wrinkle: “While removal by impeachment is final, the President may appeal a declaration of Section 4 inability an unlimited number of times,” Adam R.F. Gustafson wrote in the Yale Law & Policy Review in 2009–in Trump terms, thus setting off a seemingly endless season of The Apprentice meets Advise and Consent.

History doesn’t offer us much to go on in terms of Section 4. Although it was in effect during Watergate, those around Nixon, worried about his darkness and his drinking, took informal steps. “I can go into my office and pick up the telephone and in 25 minutes 70 million people will be dead,” Nixon told visiting lawmakers during Watergate. Afterward, California Senator Alan Cranston called Defense Secretary James R. Schlesinger about “the need for keeping a berserk President from plunging us into a holocaust.” In Nixon’s final days as President, Schlesinger instructed the military to double-check attack orders from the White House with him, thus unilaterally circumscribing the powers of the Commander in Chief.

The 25th Amendment was explicitly researched in 1987 amid speculation that the 76-year-old Reagan, hobbled by the Iran-contra affair, might be unable to carry on as President. The incoming White House chief of staff, Howard Baker, asked an aide to explore the constitutional options, but upon arriving for work, Baker realized that the President was up to the job, and talk of the amendment faded.

Which is what will probably happen with the current chatter about Trump. But in the nuclear age, there isn’t much room for error–and that means Pence and the Cabinet might want to brush up on their constitutional history, for in the most dangerous of hours it could fall to them to make some of their own.

Correction: The original version of this article incorrectly characterized Section 4 of the 25th Amendment. Once the Vice President becomes acting President in an invocation of Section 4, he, not the incumbent President, remains in power if sustained by a majority of the Cabinet (or the designated “other such body”) as the matter moves to its congressional phase.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com