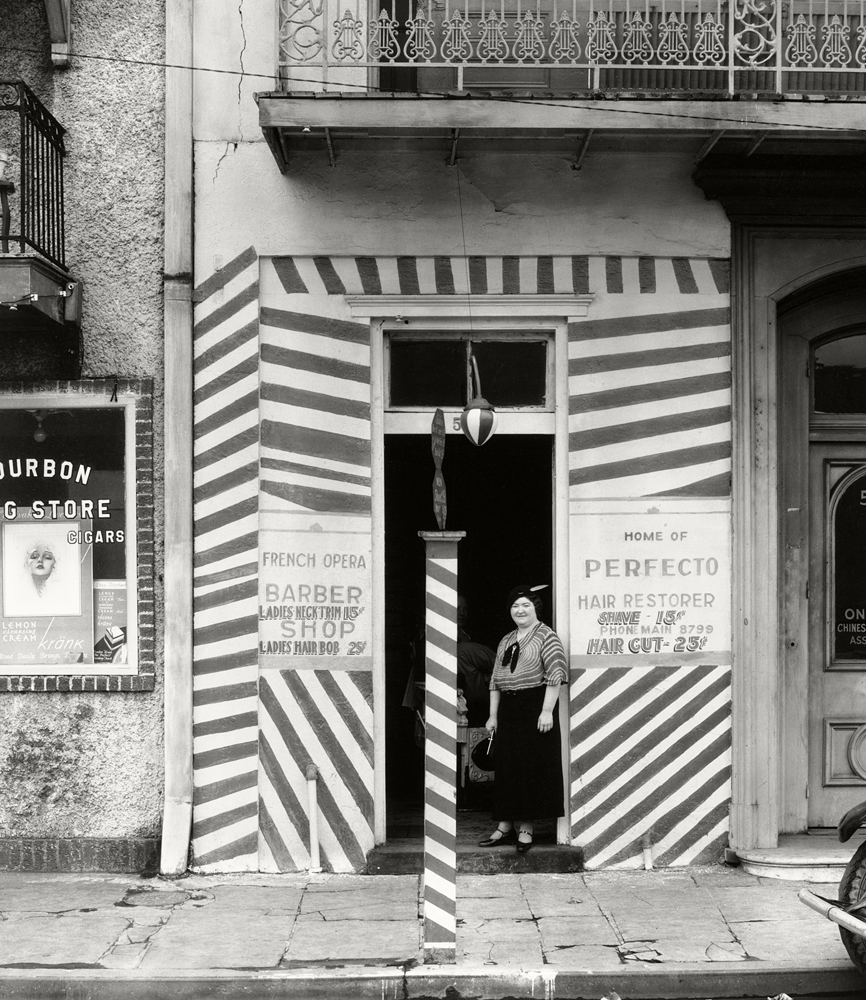

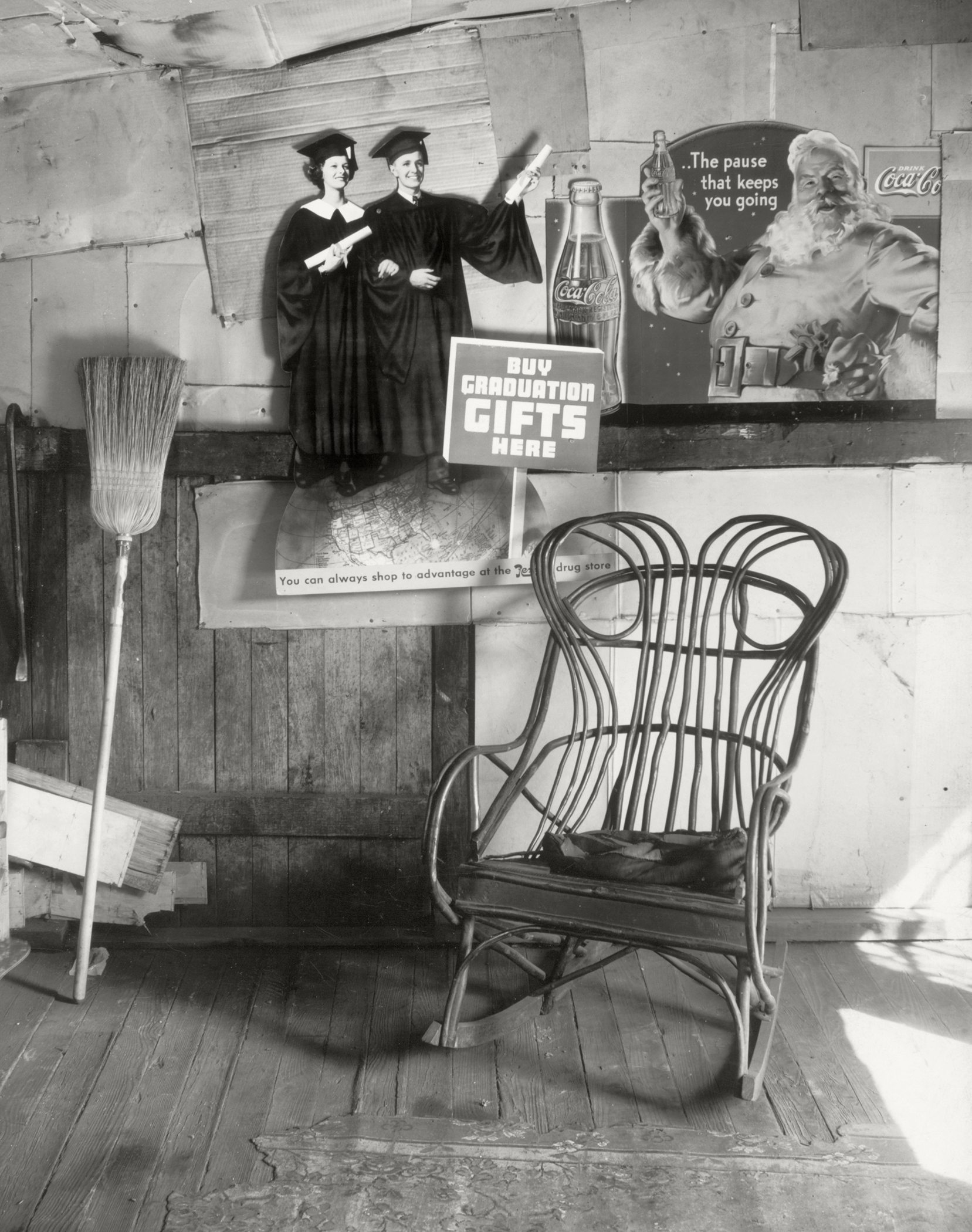

Like the work of most great artists, the best of Walker Evans’ pictures are marvels of contradiction. Or, rather, they acquire their power through the contradictions they deftly reconcile. One especially striking example: a photograph from 1930 (slide 11 in this gallery) comprised of elements so incongruous that, taken together, they really should not bear scrutiny for more than a few moments before the viewer, shrugging indifferently, moves on.

But through Evans’ uncanny visual alchemy, that particular photograph’s disparate graphic elements—family photos; a half-hidden American flag; dried flowers; a truly hideous plant growing with almost unseemly vitality from a battered wooden bucket—appear not only to belong together, but to need one another in order to make sense.

As seemingly chaotic and even unappealing as the image might feel at first glance, those wildly variant aspects of the photo—the flag, the plant, the faces—somehow cohere into something far more than the sum of their parts. Despite its initially jarring message, “Interior Detail of Portuguese House” does not, in fact, spurn scrutiny—it commands, and rewards, scrutiny. And what’s more amazing is that, after a time, the photograph appears to be gazing back. It is the viewer, and not the picture, that is the subject of an unblinking inquiry—and it’s unsettling.

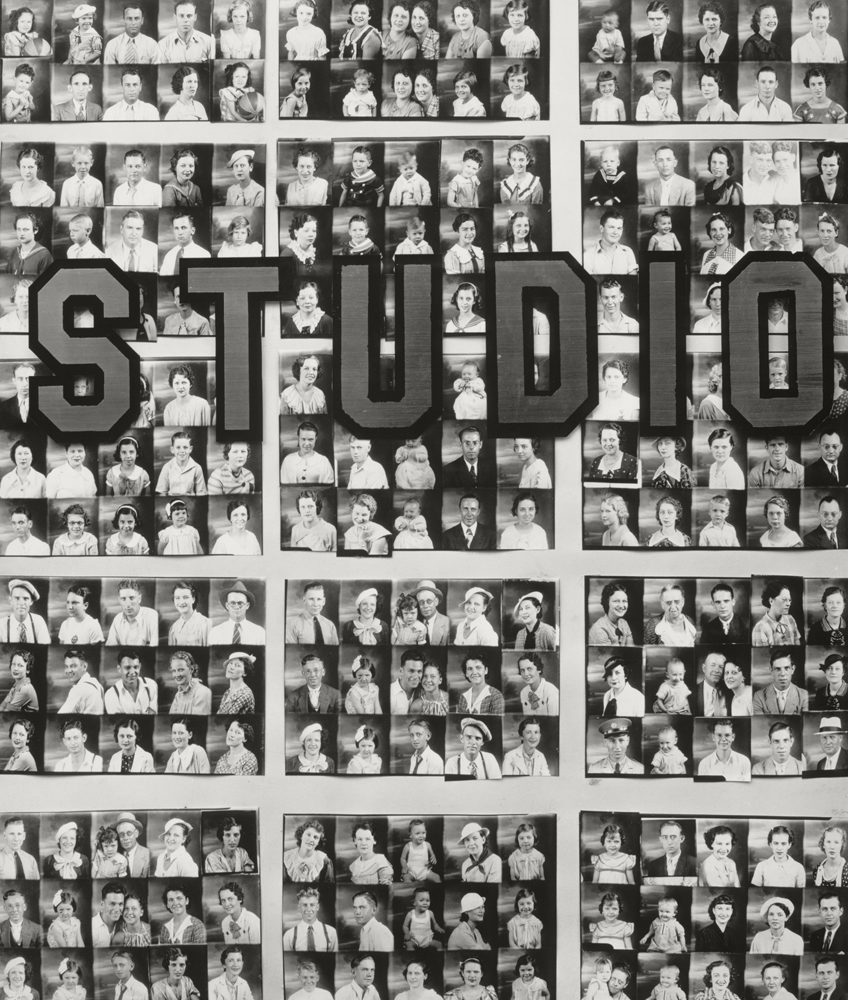

But if Evans’ pictures are evidence of a rare facility for both creating and resolving contradictions, his career might be seen as his masterpiece. A fierce, determined artist, Walker Evans was for decades on staff at Time Inc.—a salaried editor at, of all places, Fortune magazine from the 1940s until the mid-1960s. That the man behind one of the seminal photographic efforts of the 20th century—the 1938 masterwork, American Photographs—went to the office each day, like any other nine-to-fiver, might astonish those photography buffs who have always, understandably, imagined Evans as nothing if not an irresistible creative force.

And yet, here again, Evans’ intrinsic contradictions—managed as Rodin might handle a lump of clay, or Koufax a curveball—are ultimately resolved in the photographs, singly and collectively, that he produced. He is both iconoclast and working stiff; company man and virtuoso.

This year marks the 75th anniversary edition of American Photographs, reissued by the Museum of Modern Art in an edition that recaptures, for the first time since its original release, what might be called the book’s radical purity. (The book itself, as a physical object, is a pleasure to hold; the duotone plates are gorgeous and crisp, and the size of this edition—an at-once solid and easily handled 7.75″ x 8.75″ hardcover—does justice to the serious, unfussy, thrilling nature of the work inside.)

As in the first edition, Evans’ pictures in the MoMa release appear only on the right-hand side as one turns each page, the utterly blank page on the left—without even a caption to distract the eye—adjuring one to look, to really look, at each picture, one after the other. And as the pages (slowly, slowly) turn, Evans’ accomplishment grows more evident, more impressive, more engaging.

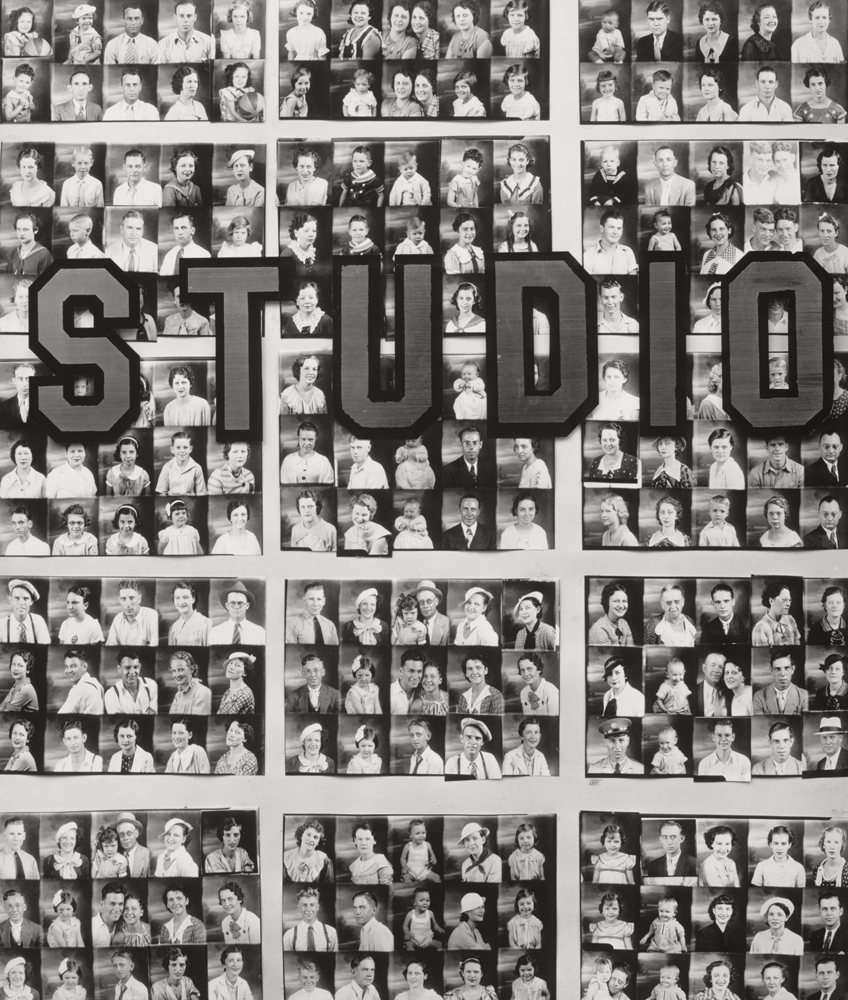

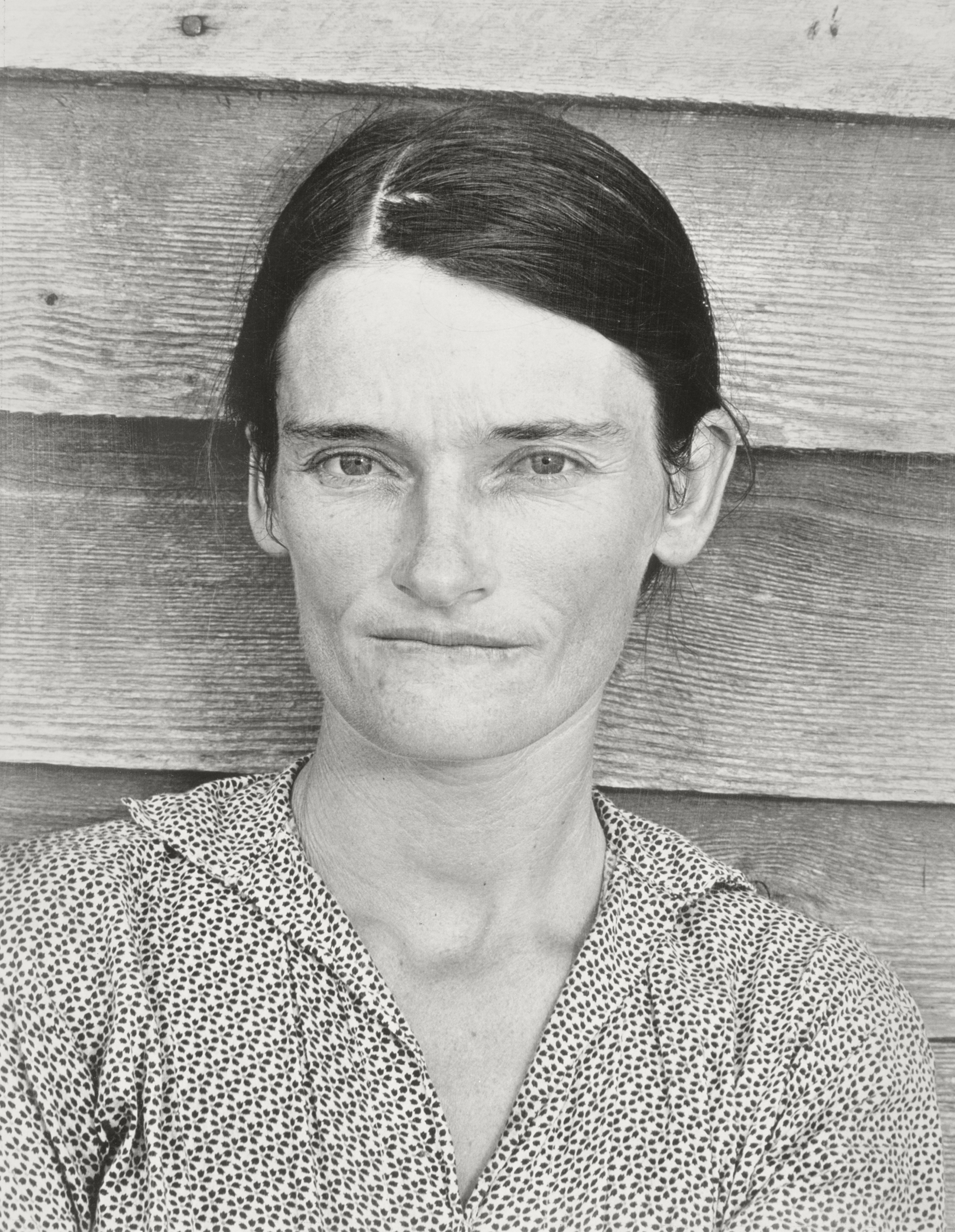

The standard line on Evans is that no one—with a camera or a paintbrush—had ever captured America in quite the clear-eyed, unsentimental, honest way that he did. But that patently true declaration still fails to encompass the scale and the sustained excellence of his achievement. In American Photographs, in images made during the Great Depression in places as divergent as Pennsylvania, Alabama, New York City and Havana, Cuba, Evans did not hold a mirror up to his country and his time: no mirror ever made, after all, could so clearly reflect what he saw, and what he wanted others to see.

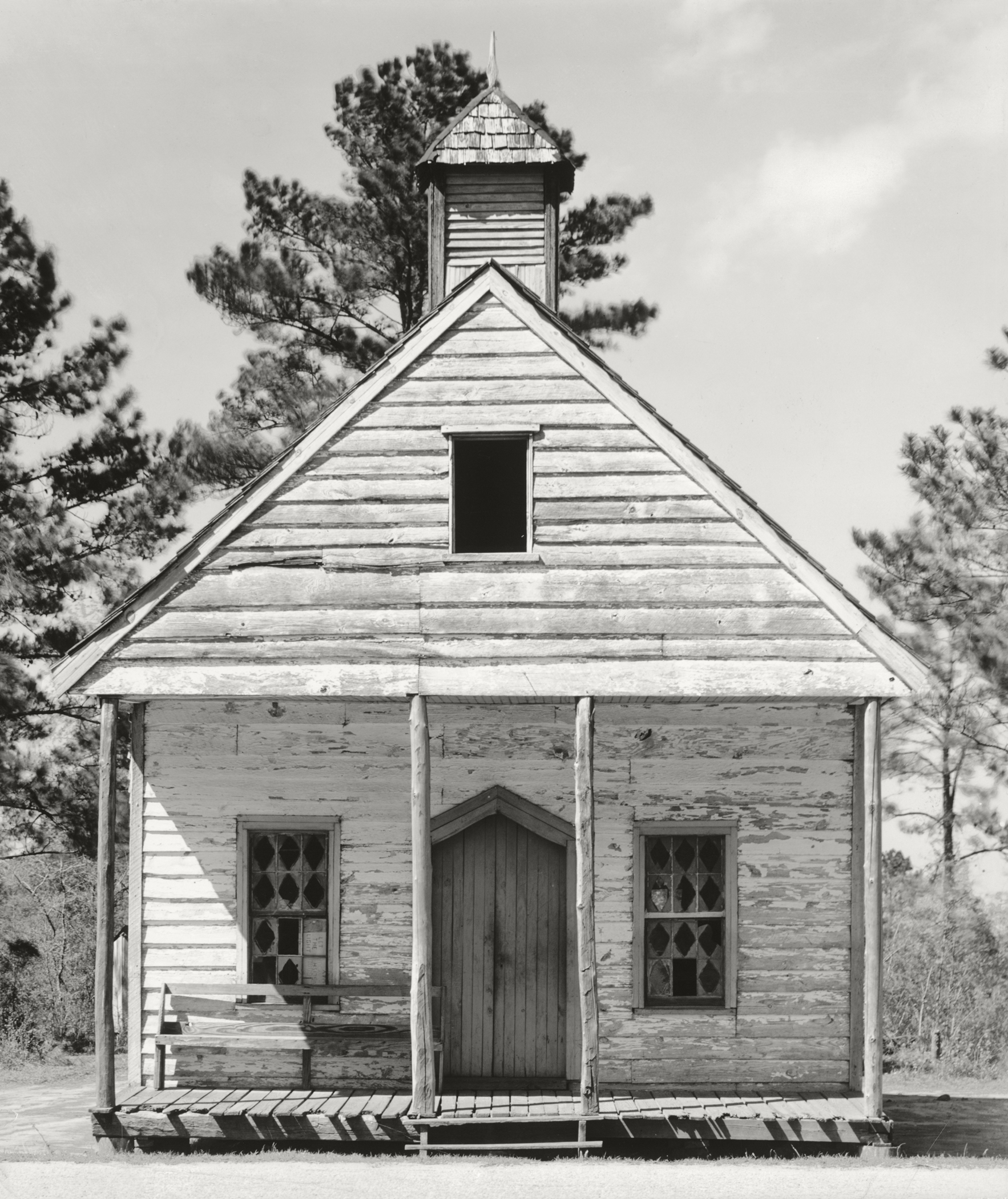

Instead, each and every one of Evans’ pictures provides a window—or an unadorned window frame—from which even the glass has been removed, and through which we witness a scene of such clarity and immediacy that our own contemporary surroundings, if only for a moment, seem somehow less freighted with history. Less grounded. Less real.

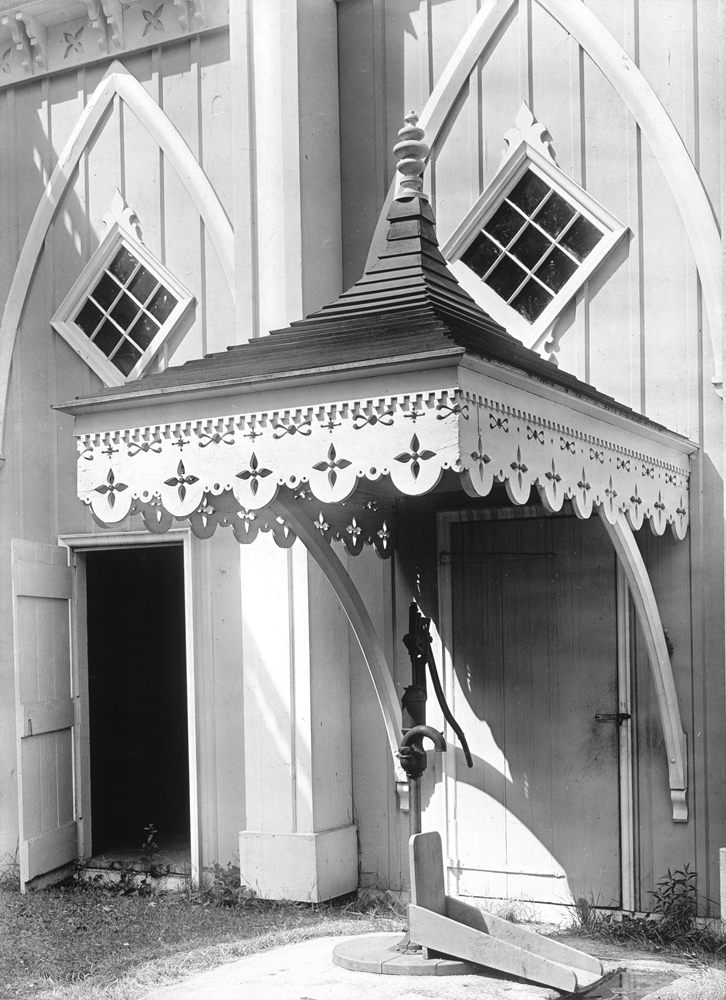

The details of a house in Maine (slide 17)—the surprisingly jaunty, seemingly tilted windows; the elegant shapes, graceful patterns and, above all, the textures that give the structure its personality—are not merely the handiwork of people who obviously cared about their hard work; the details of the house are reminders of, and tributes to, the enduring value of hard work and the attention to craft.

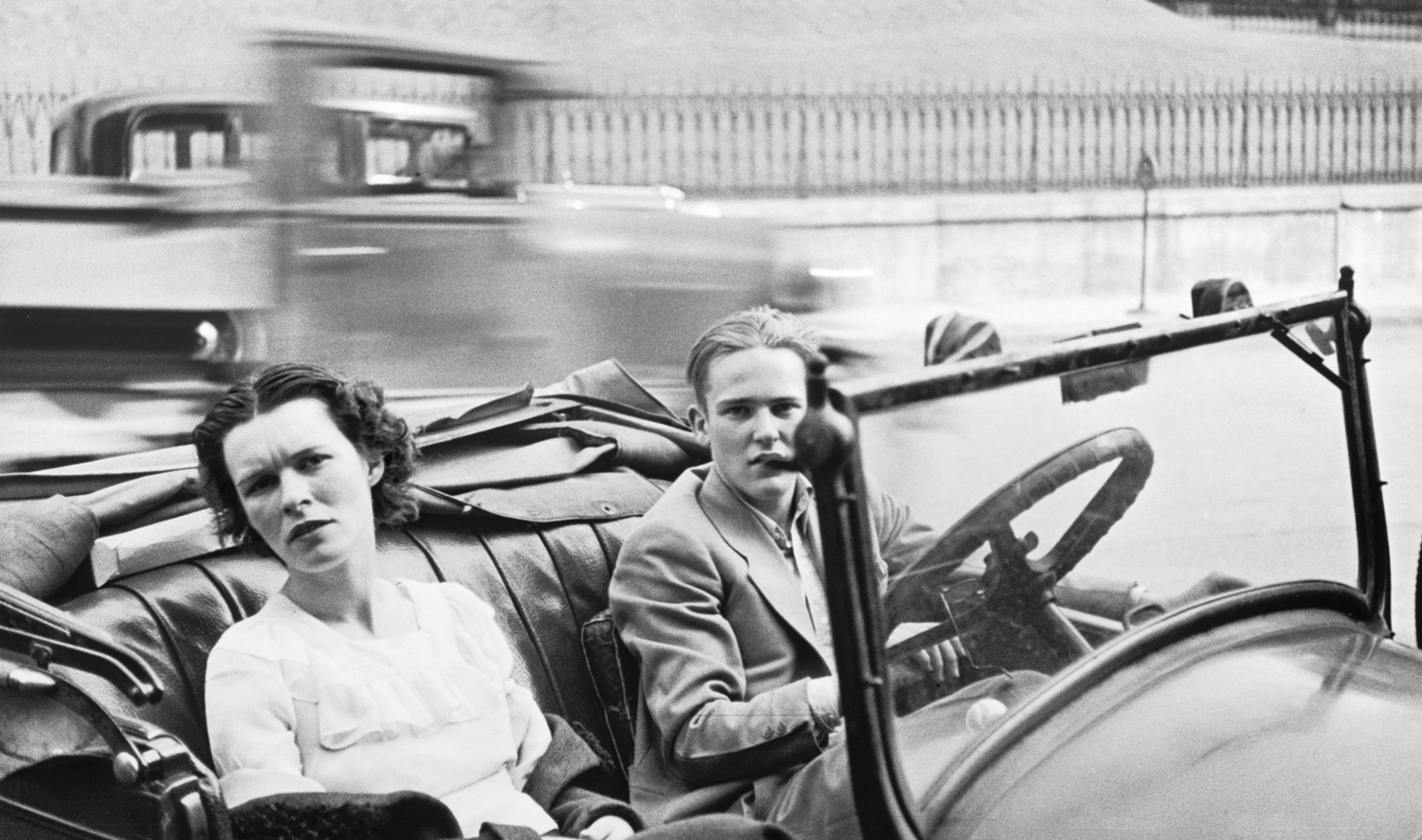

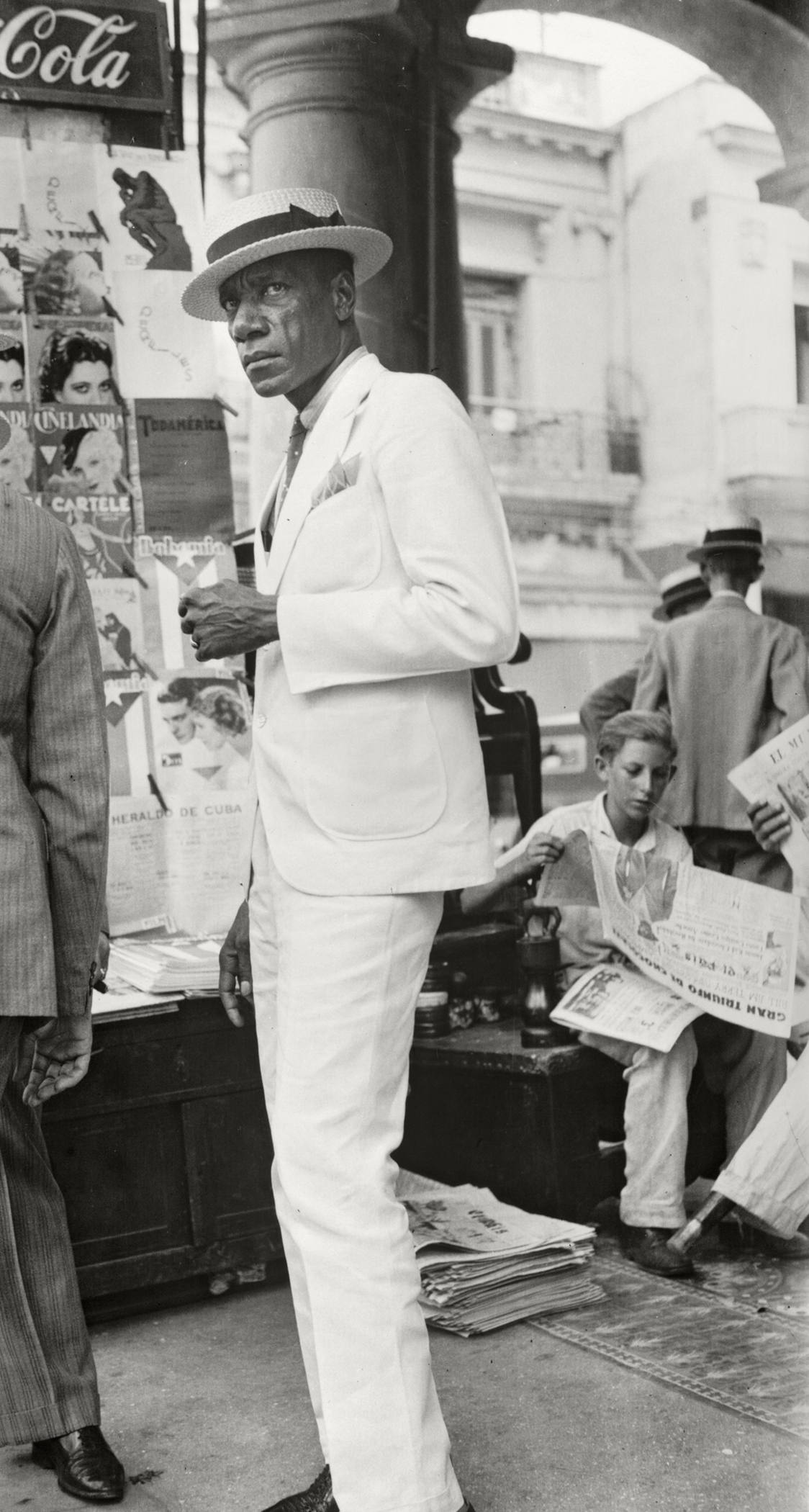

The stance, the clothing and the unreadable expression on the face of a lean, dapper citizen of Havana in 1932 (slide 9) are not merely separate elements of a snapshot: like the details of a portrait by an Old Master, they combine to suggest a time, a place and an attitude (defiant, dignified) that have survived the passing decades intact—even if, by now, the man himself must be long dead.

These pictures, and the other pictures in American Photographs, are intensely daring precisely because the man who made them worked so hard to hide—to efface—the effort that went into creating them. Each image stands on its own, while at the same time each picture references the photograph that comes before, and the photograph that follows. It is a straightforward book that stirs complex emotions. It is a treasure.

‘Walker Evans: American Photographs (Seventy-Fifth Anniversary Edition)’ is available through the Museum of Modern Art.

Ben Cosgrove is the editor of LIFE.com.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com