Do you have a question about history? Send us your question at history@time .com and you might find your answer in a future edition of Now You Know.

The question of which sound was the first ever to be recorded seems to have a pretty straightforward answer. It was captured in Paris by Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville in the late 1850s, nearly two decades before Alexander Graham Bell’s first telephone call (1876) or Thomas Edison’s phonograph (1877).

But it turns out that, while the answer is clear, the question is complicated.

Crucially, while Scott recorded the sound, he didn’t think people would ever hear the recordings he made. Instead, he thought they would read the tracings. So the first sound to be recorded was not the same as the first recorded sound to be played back. That second milestone wouldn’t come until Edison’s time.

“The idea of somehow putting those signals back into the air never occurred to [Scott], nor did it occur to any human being on the planet until 1877,” says David Giovannoni, an audio historian. That doesn’t mean you can’t hear those sounds today: in 2008, the First Sounds collaboration, which Giovannoni cofounded, managed to make Scott’s work audible. It’s also worth noting that Scott’s recording was man-made and captured sound out of the air, changing over a period of time; sound records of other kinds predate his experiments.

Patrick Feaster, a sound-media historian and First Sound co-founder, underlines the fact that the lack of playback doesn’t mean Scott doesn’t deserve the credit. “This was a full fledged record of sound, no question about that, just as a seismograph records earthquakes,” Feaster says. “No one faults seismographs for not playing back earthquakes.”

What Was Recorded

So what did Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville record? That answer comes down to which Scott’s recordings was successful enough to count.

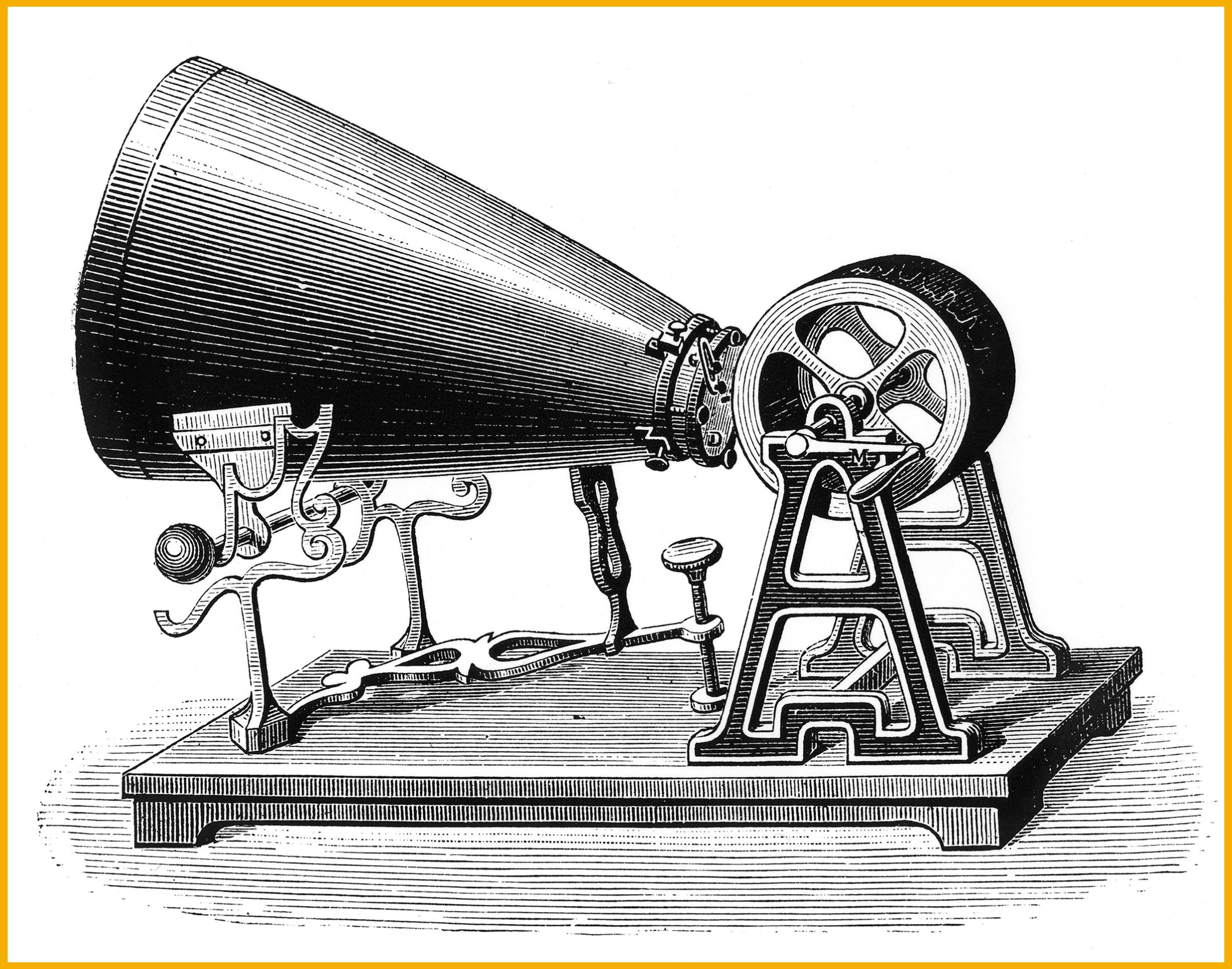

He wasn’t a professional scientist or inventor, but had aspirations to break into that world. By 1853 or 1854 he had an idea: Using the daguerreotype as his model, he thought that if a camera replicates an eye to fix image to paper, some sort of mechanical ear could fix sound to paper. Scott called his invention the phonautograph.

A vibrating membrane, working as the eardrum, was attached to a thin stylus that would trace the way the membrane moved. By covering a sheet of paper or a glass plate in a fine layer of soot and moving it under the stylus, Scott could capture the fine, wavy trail it left. A trained reader could interpret those lines — essentially the image of the sound wave — to know what the sound was. Or at least that was the plan. It turned out to be much harder than Scott anticipated for people to read words from images of sound waves; even today, though aspects of sound such as pitch or amplitude are somewhat visually interpretable in audio-editing software, that’s not really something people can do.

His early efforts are documented, but the recordings are extremely short and, Feaster says, “these were so crudely done that it’s not really clear these really count as sound recordings.” (Giovannoni once described them as a “squawk.”)

In January of 1857 Scott deposited a manuscript detailing his work and some of his early recordings with the French Académie des Sciences and described what he hoped the phonautograph would one day achieve. It could record singers or actors, or be an “automatic stenographer” to transcribe conversations. “Will the improvisation of the writer, when it emerges in the middle of the night, be able to be recovered the next day with its freedom, this complete independence from the pen, an instrument so slow to represent a thought always cooled in its struggle with written expression?” he asked. Scott believed it would happen. That same year he applied for a patent.

As he improved the recording apparatus, he switched from recording on a straight sheet of paper or glass to one wrapped around a cylinder, allowing longer recordings, but he was still moving the apparatus by hand, resulting in irregular timing. In 1859 and 1860 he recorded a tuning fork at the same time as the other vocalizations and sounds. The predictable vibration rate of a turning fork meant that Giovannoni, Feaster and others with the First Sounds collaboration could properly calibrate the time, making the recordings recognizable again. On April 9, 1860, Scott recorded a snippet of the French folk song “Au Clair de la Lune.”

The specific “first recorded sound” would thus fall sometime between the early experiments and the recognizable “Au Clair de la Lune” record. (You can listen to 1857, 1859 and 1860 recordings on the First Sounds website.) But, because the speed irregularities are so intense, it’s hard for modern researchers to know for sure whether the early recordings were successful or which one should count as first.

And it was even harder to tell at the time, given that playback equipment hadn’t been invented yet. That situation put Scott in the odd position of being essentially unable to prove that his invention worked. Eventually, he gave up on the project — returning to it, with no small sense of indignation, only near the end of his life when Edison was making headlines.

“In [one] sense he failed,” Giovannoni says, speaking of Scott’s hopes that the sound waves could be read visually. “In another sense, he succeeded wildly. The phonautograph was really the first machine to record sensory data in real time over time.”

Some scientists did see the potential in the phonautography; Rudolph Koenig, a manufacturer of instruments for the study of acoustics, sold a version through 1901, and Alexander Graham Bell used a variation of the phonautograph to make some recordings of vowel sounds in 1874.

What Was Heard

In 1877, nearly 20 years later, Thomas Edison’s “talking machine” became the first that could both record and playback sound successfully.

Edison had created a telegraphic repeater, which could automatically repeat a Morse code message and even speed it up beyond human capabilities, and in the summer of 1877 he was thinking about recording messages for telephones too. On July 17 of that year, he wrote in his notebook about reproducing a telephone message slow or fast. Edward Johnson, on a lecture circuit demonstrating Edison inventions, told his audience about the recording device Edison had begun to work on, and wrote to Edison about it. A week later Edison had sketched out some more ideas and labeled it a phonograph in his notebook.

In the months before the world learned about the phonograph — it was in November that he allowed Johnson to write to Scientific American about the device — he considered various ways of recording, switched which material would be used to capture the recording (from paper tape covered with a “soft substance” to a thin tin foil), and finally had machinist John Kreusi make his designs into a real, functioning object.

On December 7, the day after Kreusi finished making a fully fledged phonograph, Edison went to Scientific American‘s New York office with two colleagues to show off the phonograph. The magazine wrote about the visit and then explained how it worked: Edison “placed a little machine on our desk, turned a crank, and the machine inquired as to our health, asked how we liked the phonograph, informed us that it was very well, and bid us a cordial good night. These remarks were not only perfectly audible to ourselves, but to a dozen or more persons gathered around, and they were produced by the aid of no other mechanism than the simple little contrivance.”

This was the invention that got him the moniker “The Wizard of Menlo Park.” Though he would put the work aside for close to a decade before it was commercially viable — and in the meantime others, including Alexander Graham Bell, would make great strides in sound reproduction — Edison would be forever linked to the history of sound recording.

But, while there’s good documentation of that work, such is not the case for the question of which sounds they recorded while they worked on the new creation. Edison’s earliest experimental recordings, “don’t survive as playable recordings, we only know about them from notes he made in his experimental notebooks,” says Feaster, and Kreusi probably made some of them too. Early notes suggest phrases such as greetings, the alphabet and “Did you get that?” were recorded first — though Edison claimed the first thing was a rendition of “Mary Had a Little Lamb.” In any case, that song is part of what is likely the oldest sound that was recorded and intended to be play back and that still exists and can be heard. Made on June 22, 1878, at one of the public demonstrations of Edison’s work, it captured the sound of a cornet, nursery rhymes including “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” and laughter.

Edison visited Washington, D.C., in April 1878 to exhibit his phonograph and talk to Congress and the President, and it was while there he visited the Smithsonian, where he learned about Scott’s phonautograph. Reportedly, he was impressed — but surprised that someone would invent this machine but not think of playing back the recording out loud.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com