If giving back to the community more was one of your New Year’s resolutions, then good news: January is when the Red Cross and other organizations mark National Blood Donor Month in the U.S.

But while giving blood can seem like a relatively straightforward way to do something to help others, the earliest incarnations of blood donations and blood banks were anything but simple. In fact, it all started with a Soviet experiment on cadavers in the early ’30s.

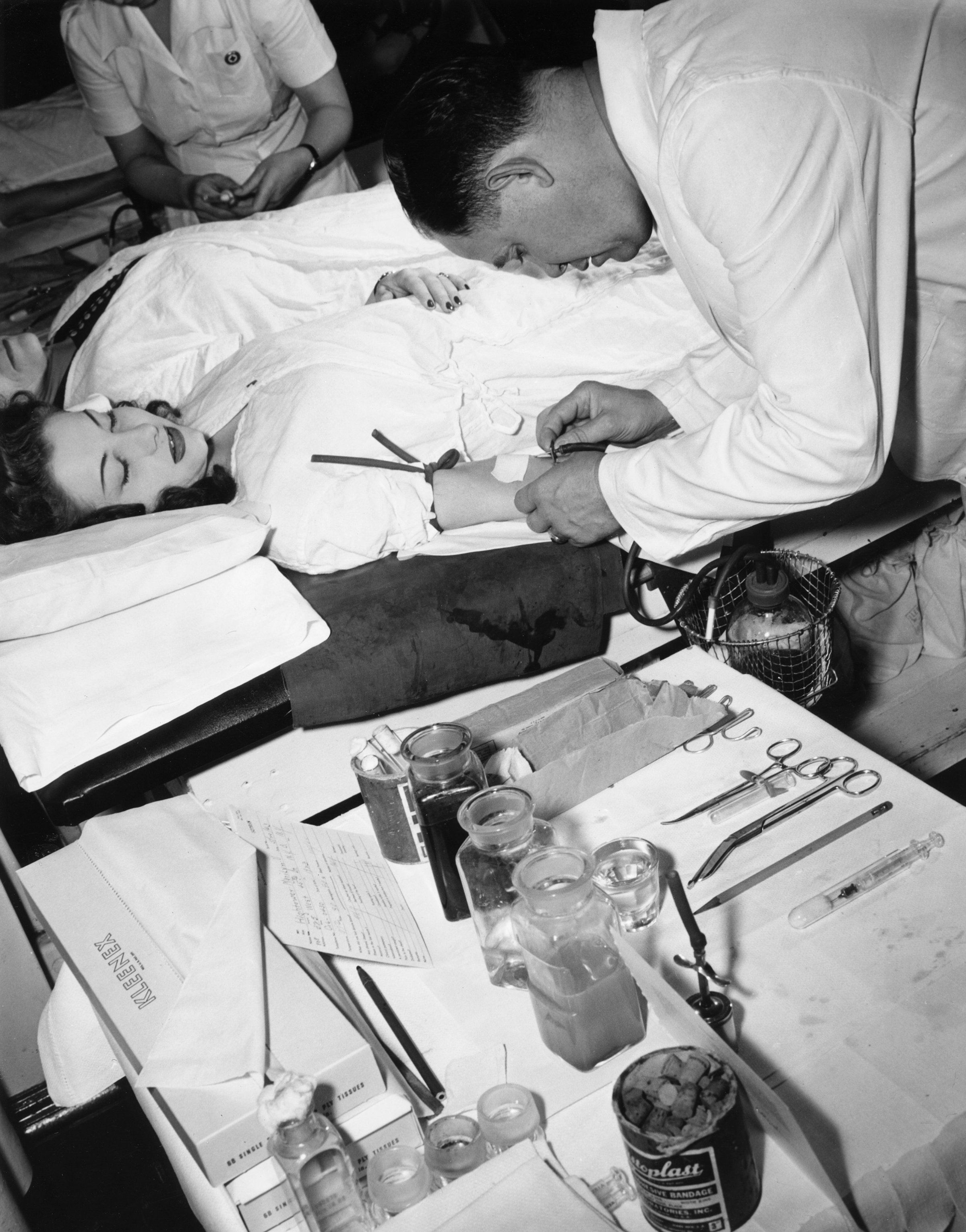

Before then, though the merits of blood transfusions were clear, getting blood donors to the people who needed the donations was a bit haphazard. For example, one method involving volunteers that was experimented with during World War I involved a tube that directly connected the artery of the volunteer donor’s arm to the recipient’s vein, which meant the two people had to be in the same room and the same time for it to work. But while that method could save some lives, it was particularly tricky in a place like Russia, where things were more spread out.

“Russia was so big, that they couldn’t get the donors to the places that they needed to go,” says Douglas Starr, author of Blood: An Epic History of Medicine and Commerce. And that’s not to mention that there simply weren’t enough donors, even if those who were willing were in the right places.

One solution was a blood bank, but that was tricky too.

“The first blood bank actually consisted of cadaver blood in Moscow,” Starr says, noting one example in which the Moscow surgeon Sergei Yudin took blood from a man who had died after being hit by a bus, and gave it six hours later to a young engineer who had tried to commit suicide on March 23, 1930. Exactly how many of these cadaver transfusions happened is not clear, as Starr notes many of the doctors who performed them didn’t publicize them for fear of backlash.

After reading about such efforts, a Chicago doctor, Bernard Fantus, had an idea. “Rather than use dead bodies, which were difficult to transport to the blood bank, he thought, Why don’t live people come in?” as Starr puts it.

The first blood bank opened on March 15, 1937, at Cook County Hospital, and it facilitated 1,354 blood transfusions in its first year of existence. Starr notes that the establishment of the blood bank model couldn’t have come at a better time, given the arrival of World War II. The war years saw a surge of patriotically-motivated blood donations, the Red Cross having collected more than 13 million pints by the end of the war.

Blood donations would peak in the Cold War era of the ’50s and ’60s, as it became more widely understood that, “in the event of nuclear war, you’ll need blood transfusion, because nuclear radiation destroys white blood cells, so those with radiation sickness have no immunity,” as Starr puts it. Plus, as advancements in open-heart and transplant surgeries grew, so did the need for blood.

Recently, however, changes in the American workplace have contributed to a decline in blood donations, Starr argues. It used to be that trucks could just roll up to factories or union halls, but now the sheer number of different types of jobs — which include ones that allow workers to work remotely — has meant it’s harder to reach a lot of people in one place. Plus, as the American adults who saw the need for blood donations first-hand during the second World War have grown older and thus ineligible to give blood, the challenge that organizations like the Red Cross face now is finding enough young donors to replace them.

But, no matter what difficulties blood-donation drives may face today, advances in the last century should be enough for donors and advocates alike to take heart.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com