Usually when the Christmas season prompts talk of the truth about St. Nicholas or Santa Claus, the problem is how to explain to kids how all those presents really get under the tree. But there’s another question history-minded holiday celebrants might ask about Father Christmas: Who was the real St. Nicholas, and how did he become associated with Christmas?

As it turns out, that story is a mysterious one too.

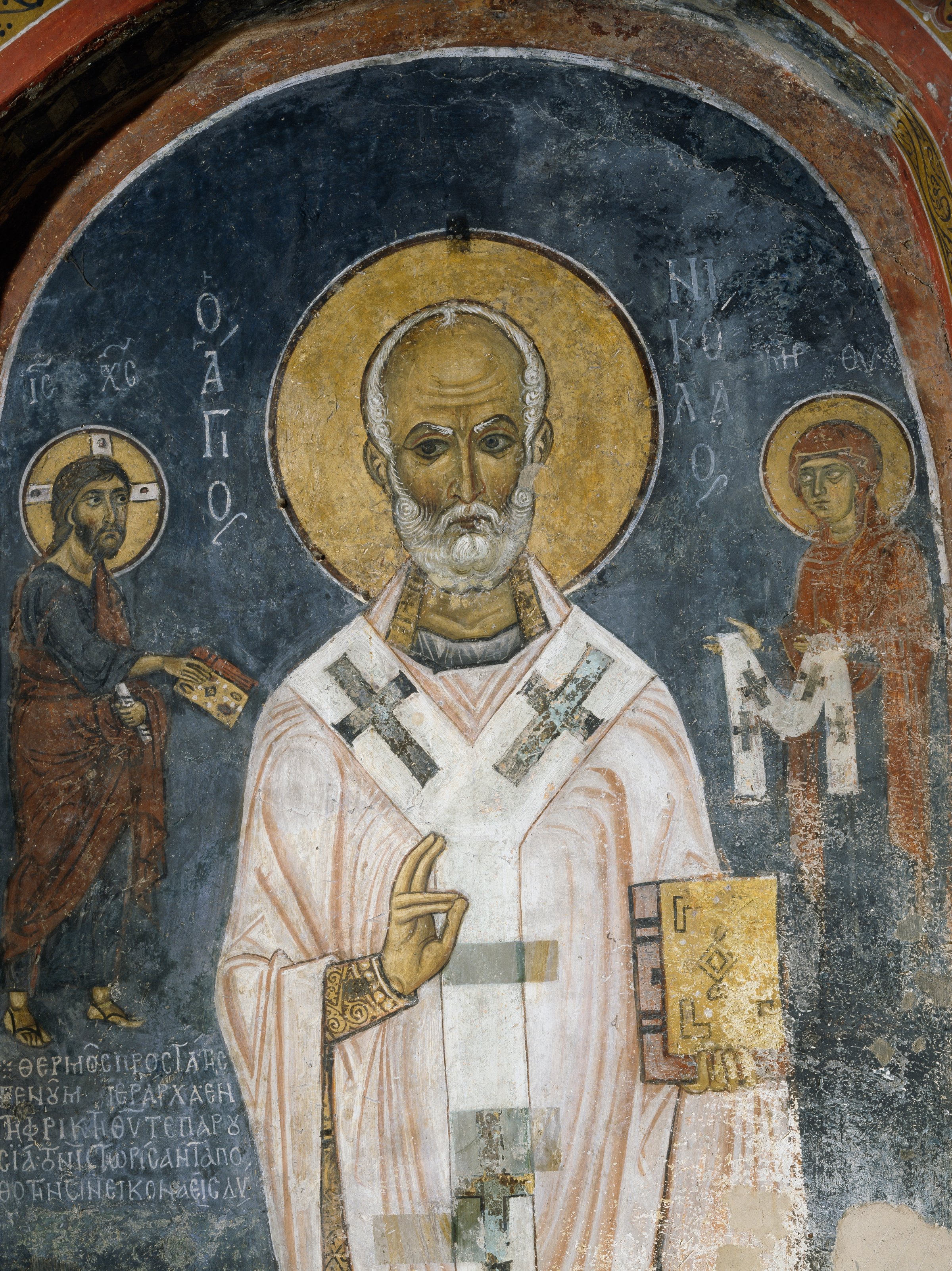

The Christmas concept of the gift-giving saint is thought to start with a riff on Saint Nicholas, who is said to have been the 4th century bishop of the Lycian Greek town of Myra (now the Turkish town of Demre). St. Nicholas Day is marked annually by many Christians on Dec. 6. However, according to Judith Flanders, author of the new Christmas: A Biography, that person is “almost certainly an invention,” because there aren’t reliable historical documents that prove he was real. All that’s left for experts to work off are writings, such as diary entries, that show what people believed him to be.

Historians do know that St. Nicholas has had a reputation for generosity, deserved or not, that dates back centuries. For example, the book The Golden Legend, which a Genoese churchman published around 1260, claimed that St. Nicholas heaved three bags of gold through a poor nobleman’s window at home so that the man could provide dowries for his three children so that they wouldn’t be sold into prostitution.

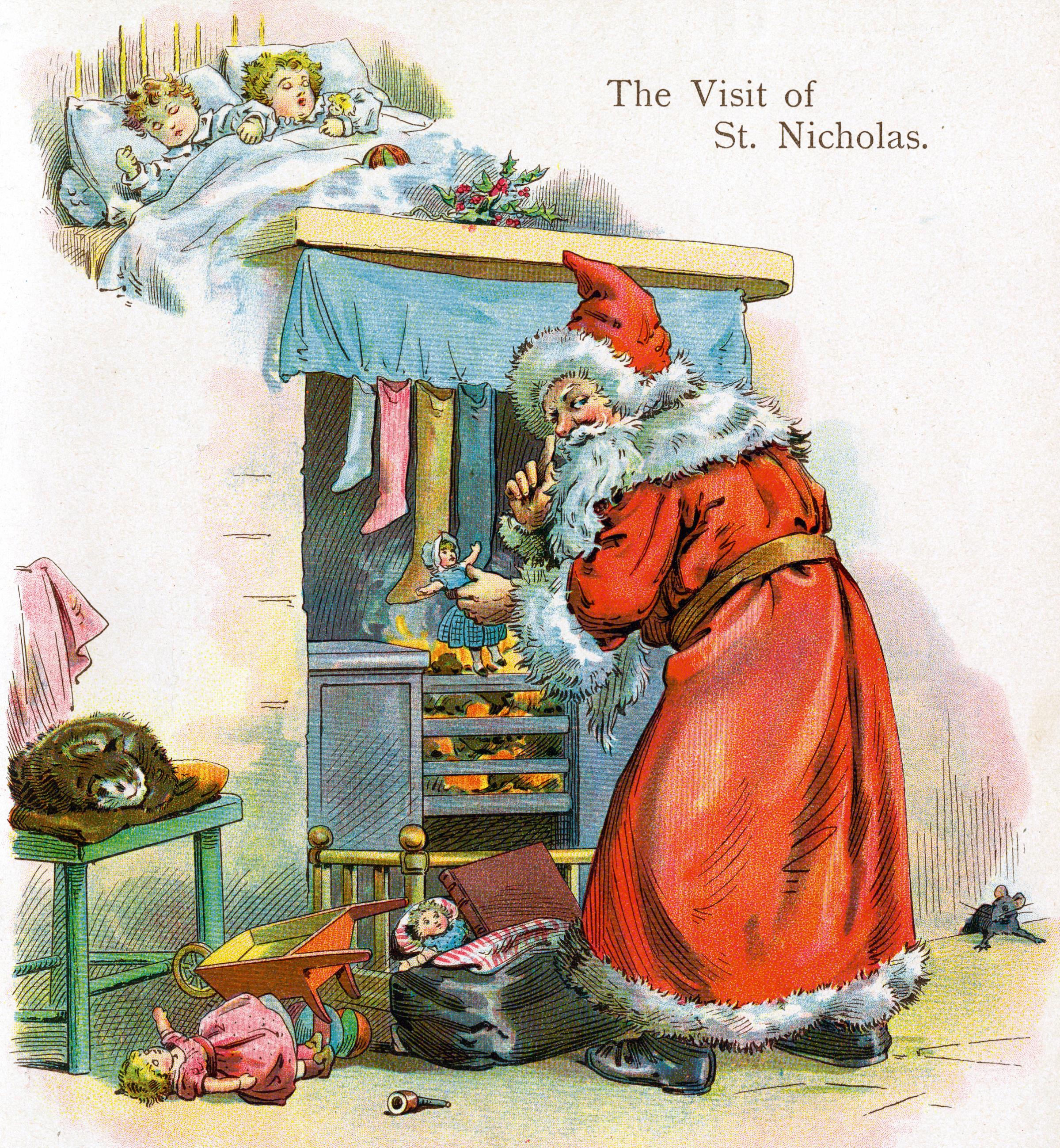

As the legend of St. Nicholas developed, that reputation stuck around. In some parts of 16th and 17th century Europe, St. Nicholas was depicted as someone who handed out apples, nuts and baked goods, symbols of a bountiful harvest. In the Netherlands, for example, St. Nicholas Day was a time for a person dressed up as the saint to go from house to house with a servant, either rewarding or punishing children depending on the work they had done. The good students got a gift meant to resemble a sack of gold, while the bad ones got lumps of coal. (Sound familiar?) In France and England, books became the gift of choice as more people became literate, Flanders notes. Gradually, small jewelry, wine and luxury foods became gifts of choice as well.

But how St. Nicholas came to North America and eventually became merged with Santa Claus is “deeply mysterious,” Flanders argues. There are two small references to Santa Claus in Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer in the 1770s, one of which refers to “St. Nicholas, otherwise called Santa Claus.” That debunks the theory that the writer Washington Irving coined “Santa Claus,” because Irving was born in 1783. And then the name or word is impossible to find in print for a couple of decades.

What Irving does deserve credit for is promoting the “mythical Dutch past” of the benevolent St. Nicholas. In his early 19th century satirical history of New York, Knickerbocker’s History of New York, he claimed that celebrating the saint was an old Dutch tradition of early New Amsterdam. He positioned St. Nicholas as a symbol of a simpler, kinder way of life at odds with the growing, more bustling New York City in the early 1800s. His version of early New York history was definitely not accurate: he mentions a church named after St. Nicholas, when in reality New York didn’t get its first church with that name until the 20th century, and glosses over the fact that New Amsterdam’s Dutch Reformed Church actually banned saints from religious observance.

“When the book appeared, people knew it was satire, but that was quickly forgotten,” Flanders says, “and it began to be treated as history.”

So what really happened? If anyone brought the name Santa Claus to the Americas, Flanders says credit should probably go to the roughly 25,000 Swiss people who settled in large concentrations in New York, North Carolina and Pennsylvania. “They came from regions that marked St. Nicholas’ day, and St. Nicholas in various dialects of Schweizerdeutsch, or Swiss-German, becomes either Samichlaus or Santi-Chlaus, both of which sound far more like Santa Claus than the latter, supposedly Dutch derivation from Sint Niklaas.”

The idea of St. Nicholas as the man who would come down a chimney to deliver presents is much easier to trace.

It was Clement Clarke Moore’s 1822 poem “A Visit from St. Nicholas” — which famously starts “‘Twas the night before Christmas” — that painted that memorable picture. As the industrial revolution made consumer goods more affordable for all, popular depictions of that version of Santa Claus increased as well, along with the traditions of Christmas cards and Christmas trees. Later that century, Christmas became a federal holiday. “Christmas customs encouraged a sense of community and unity at a time when urbanization, industrialization and the memory of the recent Civil War had made many people feel more unsettled than ever,” historian Penny Restad explained to TIME last year.

But the lack of knowledge about St. Nicholas doesn’t necessarily put a damper on the holiday — in fact, that’s part of what has allowed interpretations of him to flourish. This much is clear: St. Nicholas, now and throughout history, is whoever people want him to be.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com