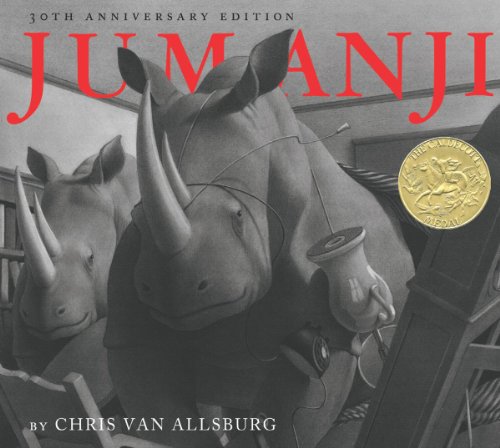

Chris Van Allsburg is responsible for some of the most iconic stories and images of American childhood. After bursting onto the picture book scene with 1979’s The Garden of Abdul Gasazi, he went on to win two Caldecott medals — for Jumanji (1981) and The Polar Express (1985) — both of which also became beloved films. His drawings are both realistic and uncanny, whether in black and white, sepia or color, and they take children on previously unimagined adventures. TIME caught up with Van Allsburg, 68, who continues to write children’s books to this day, ahead of this week’s release of the Jumanji reboot.

Van Allsburg: You may hear some barking in the background because I have a new puppy.

TIME: What kind of puppy is it?

It’s a miniature schnauzer.

So not like the one that you have in all of your books.

Well, that’s a bull terrier, and that’s probably more dog than I can handle at my age.

Why did you put that bull terrier in all of your books?

When I wrote my first book, I had in mind that the story would include a dog, and the dog I had in mind was a bull terrier. I found them peculiar looking and charming in an idiosyncratic sort of way, but did not have access to one. My brother-in-law was visiting around that time, and he told me that he was about to acquire a golden retriever. I told him, “Gee, that’s such an ordinary dog, you should get something a little more interesting, a little more exotic.” And he said, “Like what?” And I said, “You should get a bull terrier.” I sold him on the idea, and I used the dog that he had acquired as my model for the dog in The Garden of Abdul Gasazi.

He unfortunately passed away — he had an accident, so he didn’t live that long. I made a decision when I started the second book, which was Jumanji, that as long as I kept on doing books I would provide the dog a cameo appearance. In Jumanji he’s a pull toy, in The Polar Express he’s a hand puppet… I have gone to book stores and done signings of new titles and seen kids rifling through the books without reading them because the first thing they want to do is try to find out, where’s Fritz?

How did you come up with the idea for Jumanji?

I think most authors who write for children are revisiting their own childhood. I recalled as a child being interested in playing board games, but always at the same time being slightly disappointed because it was all pretend. When you bankrupted your parents when they landed on Boardwalk, and they had to hand over all their money, it just wasn’t real. So I had in mind this idea that it would be great if there were board games that actually delivered what they promised. With that in mind I contemplated different kinds of games where that might produce an interesting result, and I settled on a jungle adventure game, because of the cognitive dissonance — you know, rhino stampede, we’ve all seen that, but you’ve never seen a rhino stampede in a dining room.

How involved were you in the first movie adaptation?

I was pretty involved. The studio had optioned it and had commissioned some screenplays and weren’t really happy with it, and it looked like they were maybe going to abandon the project. So I started writing out some ideas, and the studio liked the treatment, and I actually wrote a script which then, as many scripts are, was really only a starting point for a development process. That initial script I wrote was rewritten many times, and then finally made into Jumanji. So I was a contributor of some story material that was not from the book, and the studio gave me a story credit but not a screen credit, because so many screenwriters had worked on it after I made my contribution.

How involved are you with the new one?

Very little, nothing like the involvement I had with the first one. This is a project that was really energized not so much by my original book but by the success and fandom of the first film. It was more like, not really even a sequel to the first film, but more I think the jargon in Hollywood is a “reboot” — basically taking some of the same thematic material and then reconsidering it fairly liberally or fairly — what shall I say — fairly aggressively, without a clear obligation to characters from the first one or following through some story arc, that sort of thing.

The children’s adventure in Jumanji is prompted by boredom. Could you write the same book today, in the age of the devices and screens?

I still think boredom is a reality for children, and frankly I think that the continuous contact with screens, while it may seem more stimulating just because things are moving, I think there’s probably a level of boredom even with that, where it’s not real life and it’s a facsimile of experience. I think the new film actually confronts that a little bit, because as you may know it’s no longer a board game, it’s now a video game. And the jungle does not come to the players, the players go to the jungle. I’ve seen the film and while I can see that it has very little to do with what I wrote besides sharing a title, it’s an amusing and entertaining ensemble piece.

You have such a distinctive visual style. How did it evolve?

My background is in sculpture. I studied sculpture for the entire time I went to art school, and as a result didn’t really acquire picture-making skills that I might have if I was studying illustration or painting or something like that. I became adept at using a pencil, because a pencil is pretty much what I used when I was sketching out the sculptures that I would make. So I could draw pretty well, and a few years after I had been out of graduate school, I decided I would give a shot at a children’s book. When I had to choose materials, it wasn’t like I was making a decision about using watercolors or pastel or something because I knew nothing about those materials — all I knew really was pencil and charcoal pencil.

With respect to style in terms of composition and point of view, I was influenced by surrealism. As a younger artist I always liked pictures that appeared to present a familiar reality, but because of the writing, because of the point of view, perhaps because it was a solitary space with a single figure in it, it took on a kind of power and mystery that you definitely feel but can’t account for.

Which of your books do you think your readers like best?

I guess that would have to be The Polar Express. I don’t do a lot of book signings anymore, but I was invited to a school the other day. The children were four and five, and they had built a Polar Express train out of cardboard and painted it. They were all dressed in their pajamas. I went and read them the story while they pretended they were sitting — well, they weren’t pretending, they were sitting in the train—and so I would have to say, there’s a book that’s found its audience and had an effect on them.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com