As Republican Roy Moore and Democrat Doug Jones face off in Alabama’s sixth special U.S. Senatorial election on Tuesday, many Americans likely see the results as a reflection on President Trump, but one Alabama historian sees the results as instead reflecting a dramatic and historic shift in the demographics of the state’s voter base.

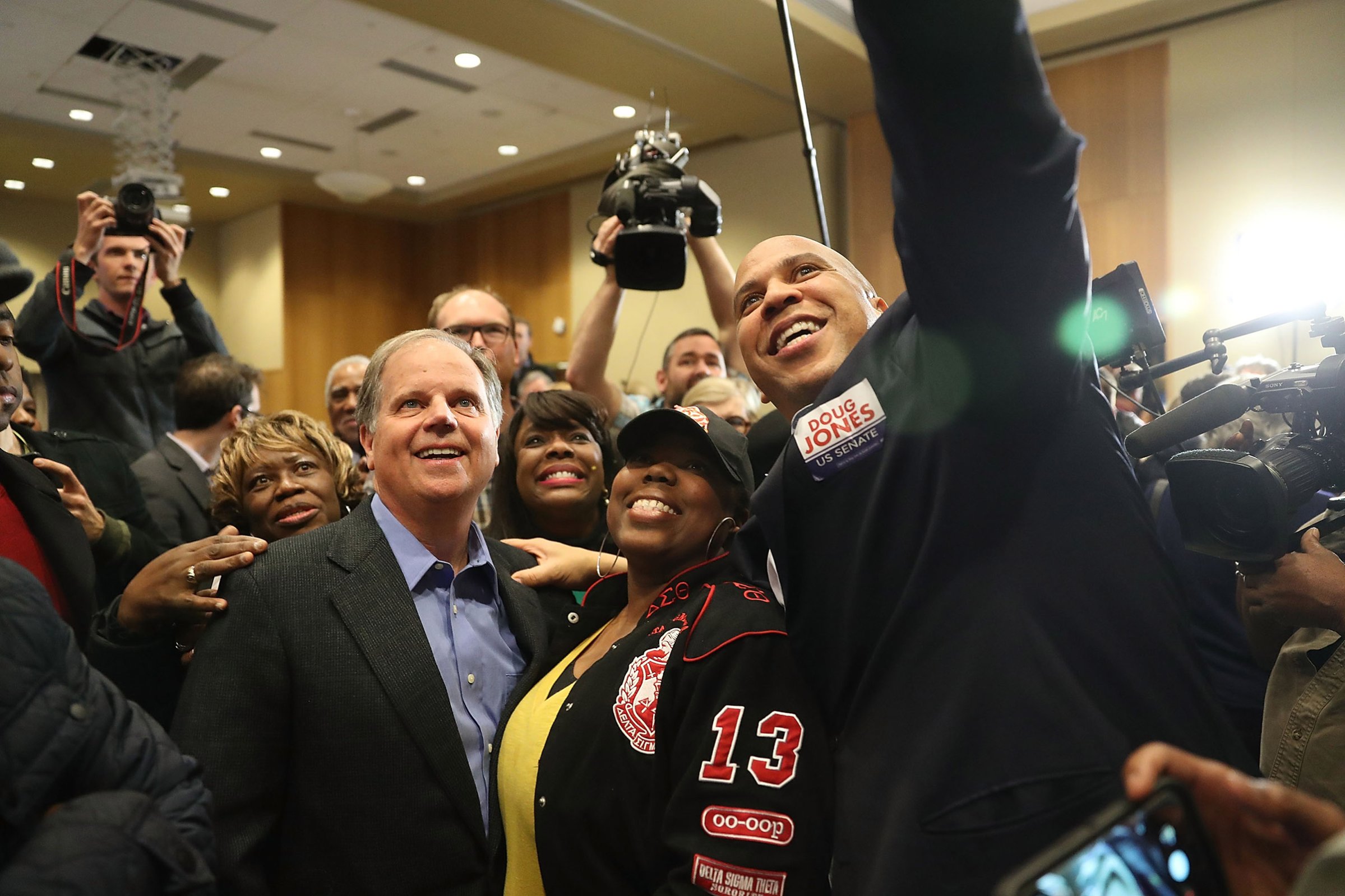

Jones — who has been framed in campaign ads as someone who “took on the Klan and got justice,” because he prosecuted white supremacists involved in the 1963 Birmingham church bombing — will have to score big with the state’s black voters if he stands a chance of winning. But, when the history of Alabama special elections began, those voters were largely disenfranchised.

The state’s first special election for the U.S. Senate fell on May 11, 1914 — making Alabama the third state (after Georgia and Maryland, respectively) where voters directly elected a U.S. Senator after the ratification of the 17th Amendment in April 1913. Before 1913, state legislators had picked U.S. Senators, but news reports of bribery and corruption had driven a push for reform around the turn of the 20th century. Since the amendment’s ratification, states can choose how to fill U.S. Senate vacancies, and depending on when the vacancy occurs, either the Governor appoints someone to serve the remainder of the term or a special election is held.

It was the Aug. 8, 1913, death of Alabama’s Democratic U.S. Senator Joseph Johnston that created a Senate vacancy that the Los Angeles Times described as “the first to test the authority of a Governor to fill a vacancy since the direct election amendment to the Constitution was adopted,” as quoted by the election history and predictions website Sabato’s Crystal Ball.

Democratic Governor Emmet O’Neal wanted to appoint Rep. Henry Clayton, Jr. in the interim, but President Woodrow Wilson needed Clayton in the House to pass certain antitrust legislation. Then, the state legislature blocked the Governor’s effort to appoint Birmingham News editor Frank Glass to the seat. With the Governor out of options for an appointment, a special election was the only avenue left. In the election, Frank White, a Birmingham lawyer, won his party’s nomination with 60% of the vote in April 1914 and went on to be elected on May 11, 1914. He served until March 3, 1915.

But, though the 17th Amendment at that point allowed for Americans to elect their U.S. Senators, that didn’t mean all of the people in the state could vote in the special election.

The Alabama voter base at the time was limited by state restrictions on voter registration, such as a poll tax and literacy test enforced by the 1901 Constitution, according to historian Wayne Flynt, an expert on Alabama history and the author of Southern Religion and Christian Diversity in the Twentieth Century. The state’s constitution had been hashed out by lawyers, industrialists, bankers, planters and other businessmen who made up a state Constitutional Convention that met 1901. They came up with a poll tax, a literacy test and a property-ownership requirement to vote. These moves disenfranchised both blacks and working-class whites. Some men could avoid taking the literacy test if they had served, or had fathers or grandfathers who served, in the Spanish American War, the Civil War or the War of 1812, a loophole that favored white voters. But when it came to special elections, the poll tax was particularly onerous for all of Alabama’s poor. That’s because, even if a person had wanted to put aside the roughly $1.50 a year it took to be allowed to vote, special elections were necessarily a surprise hit to voters’ wallets. “You thought there was no reason to pay the poll tax, so you’d have a big crop of change you owed,” says Flynt.

But, Flynt explains, because of that dynamic, organized labor in early 20th century Alabama saw an in: help labor-union members get registered and pay those taxes, and their influence would climb. Alabama at the turn of the century had the highest percentage of industrial workers in the labor force of any other southern state and the highest percentage of labor-union members, peaking in the 1930s. The figures involved in that 1914 special election (White, O’Neal, and Glass) were part of the backlash against that force, large landowners determined to control labor unions and deter sharecroppers from organizing and striking.

Notably, one of those labor-mobilizing forces was the Ku Klux Klan. Especially after the 1901 Constitutional Convention, rural and working-class whites in Alabama saw the establishment as shutting them out of power. Combined with racism and isolationism, those forces helped the KKK move toward its second period of major influence, in the 1920s. As a result of that dynamic, one of the many effects of the rise of the KKK was that, in addition to the racist vigilantism for which the group is best known, their role in the labor movement helped white voters who might have otherwise been kept away by the poll tax, while that fine still prevented black citizens from voting.

“The number-one center for Klan activity in America in the 19-teens was Atlanta, and number two was Birmingham,” says Flynt. “That was an insurgency that terrified White and O’Neal. All of a sudden they realize something that was going on that was mobilizing huge numbers of ordinary people — textile workers, coal miners, railroad brotherhoods — around the Klan. They had been shut out of the political order, but the KKK gave them access to it.”

Though White won that 1914 election, those forces got what Flynt calls their “revenge” in 1926’s elections, when every Alabama statewide office went to a member of the KKK.

African Americans’ power as a voting bloc wouldn’t start to emerge until more than 50 years later when the Voting Rights Act was enacted, though disenfranchisement is still a concern. On Tuesday, as Alabamians and others around the country await the election results — as some polls show Jones leading by as much as 10 points, and another showed him losing by as much as 9 points — the closeness of those polls are a reminder once again of how much a vote can make a difference, and of the complicated and often painful history of who gets to exercise that power.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com