When Star Wars: The Last Jedi officially opens on Friday, it will represent one more milestone in the long history of Disney, the company that bought Lucasfilm — and thus the Star Wars franchise — for $4 billion in 2012.

But Friday’s date — December 15 — is important in Disney history for another reason: it’s also the anniversary of founder Walt Disney’s death in 1966.

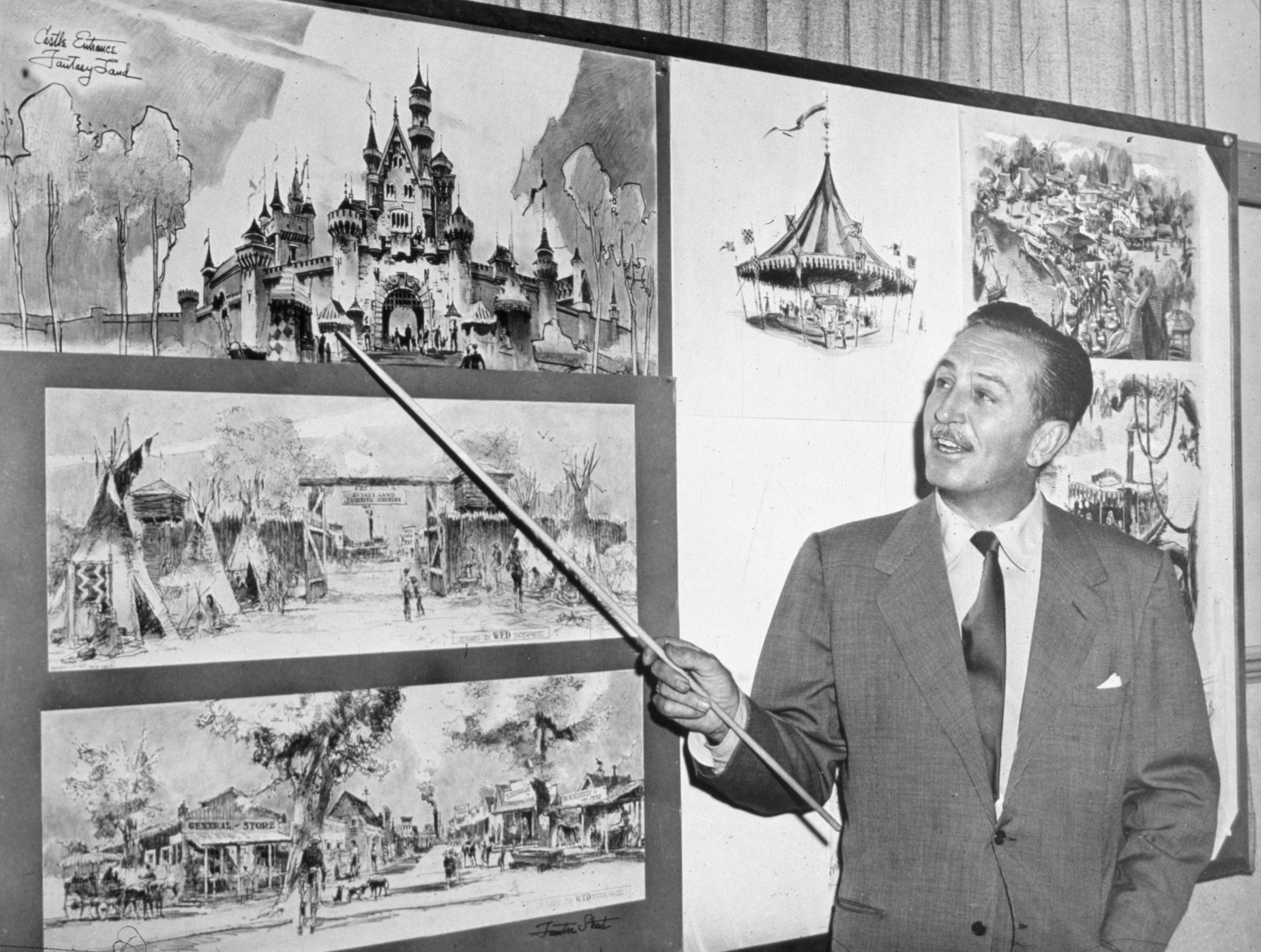

Though Disney died of cancer relatively young, he forever changed the way stories are told, among other accomplishments. From the birth of Mickey Mouse in 1928 to the nature-centric documentaries he produced in his later years, his personal vision permeated the culture, as TIME explained in its remembrance of the animation innovator:

The mythmaker is a primitive. He molds his fantasies out of primordial impulses that are common to all men. In an age of reality, he is a rarity, for he celebrates an innocence that does not mix well with the times. Walt Disney was such a man, molding myths and spinning fantasies in which innocence always reigned. Literally billions of people responded out of some deeply atavistic well of recognition, and they lavished their gratitude on him. Soldiers carried the cartoon-figure emblems of his creations on their uniforms and their war planes. Kings and dictators saw them as symbols of some mysterious quality of the American character. David Low, the great British cartoonist, called Disney “the most significant figure in graphic arts since Leonardo.” Harvard and Yale gave him honorary degrees in the same year (1938); on his shelves were more than 900 citations, including an unprecedented 30 Academy Awards.

When he died last week of cancer at 65, Disney was no longer simply the fundamental primitive imagist (the psychedelic merchants preempted that role), but a giant corporation whose vast assembly lines produced ever slicker products to dream by. Many of them, mercifully, will be forgotten, but the essential Disney creations, the cartoon comics, the full-length animated features such as Fantasia, Snow White, Bambi, Pinocchio, Cinderella—even that fantasy-filled 300 acres of dream puff called Disneyland—will remain as monumental components of American culture.

It was in the early days of film animation—1928—that Disney labored and brought forth his Mouse. Mickey was the first situation comic: saucereared, squeak-voiced (it was Disney’s voice on the early sound tracks), perfectly sensible, always cheerful, and eternally scampering in and out of trouble. He and the rest of the Disney bestiary were instantaneous hits with audiences primarily because they were anthropomorphic, hilarious because they were so incongruous. The loose-limbed, dim-witted dog Pluto was an unequal match for a piece of flypaper. Goofy was also a dog, but with more human attributes, who introduced each of his maundering reflections with a delicate hiccup. He starred in a series of “how to” films in which he lamentably embarked on the study of every sport from football to horseback riding. After Mickey, the most famous character was, of course, that choleric, put-upon, slap-stuck Donald Duck, easily the most ridiculously funny fellow ever put on film.

In The Three Little Pigs (1933), Disney foreshadowed the work of his full-length films. Crisp in color, jaunty in jingly music (Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?), the movie was also a significant departure in its simply stated moral theme. In Snow White, Disney and his staff met the challenge of creating believable characters. Each of the seven dwarfs, from sober-sided Doc to dim-bulb Dopey, had a distinct personality. In Cinderella, a handful of Disney creations nearly stole the show: the bloodthirsty but fatuous cat Lucifer, and the nimble mice, Jaq and Gus-Gus. Millions of children the world over grew up convinced that Disney wrote as well as drew such tales as The Sleeping Beauty and Peter Pan. And there are grown men and women today who, recalling Fantasia, cannot hear the Dance of the Hours without visualizing the delicate prancing of Disney hippos and elephants, or The Sorcerer’s Apprentice without seeing Mickey Mouse trying to dam the flood wrought by a many-splintered broom, or A Night on Bald Mountain without shuddering at Disney’s crackling thunderbolts and the satanic wingspread darkening a tumultuous sky.

In concluding the obituary for Disney, TIME noted that, though the flag flew at half-staff at Disneyland, Walt’s death did not distract theme-park visitors and moviegoers from the enjoyments he created. The show, as it was, went on. With the latest sure-to-be-blockbuster Disney release, it still does, just as Disney would have wanted. “He saw his own role,” TIME observed, “as the fantasist animating the warm dreams that men and children refuse to let die.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com