Milestone moments do not a year make. Often, it’s the smaller news stories that add up, gradually, to big history. With that in mind, in 2017 TIME History will revisit the entire year of 1967, week by week, as it was reported in the pages of TIME. Catch up on last week’s installment here.

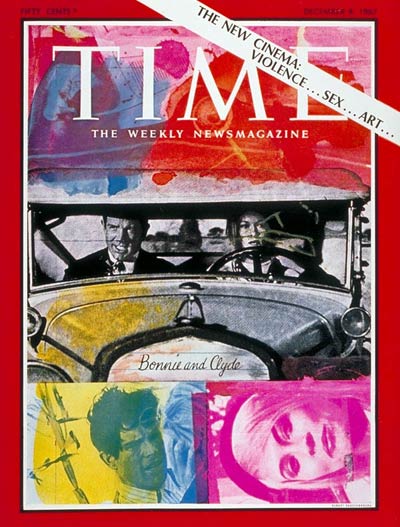

Anyone who remembered the negative review that TIME gave Bonnie and Clyde when it was released in the summer of 1967 might be surprised to see the film show up on the cover months later, getting a second appraisal. And what an appraisal it was. “Bonnie and Clyde is not only the sleeper of the decade but also, to a growing consensus of audiences and critics, the best movie of the year,” the story proclaimed.

Though the movie got a second look on its own merits — the original critic had failed by trying to pass judgment on how faithful the plot was to the true story on which it was based, the reassessment concluded — it was thus highlighted for a different reason. Bonnie and Clyde stood in for a whole new movement in American cinema, in which Hollywood was producing films that enjoyed “a heady new freedom from formula, convention and censorship.” Movies, in short, were more exciting than ever:

Newness is not merely a matter of time but of attitude. Despite the legacy of such rare masters as D. W. Griffith and Sergei Eisenstein, the vast majority of films a decade ago were little more than pale reflections of the theater or the novel. The New Cinema has developed a poetry and rhythm all its own. Traditionally, says Cahiers Editor Jean-Louis Comolli, “a film was a form of amusement—a distraction. It told a story. Today, fewer and fewer films aim to distract. They have be come not a means of escape but a means of approaching a problem. The cinema is no longer enslaved to a plot. The story becomes simply a pretext.”

Whether or not filmmakers want to tell a story, they no longer need adhere to the convention that a movie should have a beginning, middle and end. Chronological sequence is not so much a necessity as a luxury. The slow, logical flashback has given way to the abrupt shift in scene. Time can be jumbled on the screen—its foreground and background as mixed as they are in the human mind. Plot can diminish in a forest of effects and accidents; motivations can be done away with, loose ends ignored, as the audience, in effect, is invited to become the scenarist’s collaborator, filling in the gaps he left out. The purposeful camera can speed up action or slow it down; the sound track can muddle a conversation or over-amplify it to incoherence. Black-and-white sequences intermingle with color.

Comedy and tragedy are no longer separate masks; they have become interchangeable, just as heroes and villains are frequently indistinguishable. Movies still make moral points, but the points are rarely driven home in the heavy-hammered old way. And like some of the most provocative literature, the film now is apt to be amoral, casting a coolly neutral eye on life and death and on humanity’s most perverse moods and modes.

One reason for the change, some experts guessed, was that the American movie-going public had — thanks in part to television — become too used to video to be amused by what they had once loved. Moreover, where people had once seen going to the movies as an exciting outing, regardless of the film itself, now they went to see a particular movie, added Paramount’s Robert Evans.

And newness, it appeared, was working: Bonnie and Clyde had not only received Hollywood’s rare second chance, it had also been a hit.

Person of the Year: In the letters section, readers began to chime in with their suggestions for who should be 1967’s Man of the Year, as the TIME franchise was then called. The nominations ran from Richard Nixon to Charlie Brown to “Mr. Average Citizen” because, as that reader put it, “Who else could have watched, listened to, and read the events of 1967 without having rioted, smoked pot, sat in, become a hippie, took a trip, struck, or protested the war in Viet Nam?”

Goodbye McNamara: This week’s national news section marked the departure of Robert McNamara as Secretary of Defense, who was shaking up Washington, D.C., by leaving government to become President of the World Bank. Though the news was heralded as so dramatic that it was “as if the Washington Monument had toppled from marble fatigue,” in fact it represented an elegant solution for President Johnson and for McNamara, who were able to use the career change to get McNamara out of a position that had become awkward without it seeming like a resignation or a firing.

Nuclear aspirations: In observing the 25th anniversary of Enrico Fermi’s success at creating a self-sustaining nuclear reaction, TIME noted that one of the atomic age’s biggest successes was in the field of nuclear power, and predicted that by 1980 nuclear power would account for one-third of all U.S. energy needs. In fact, according to the World Nuclear Association, nuclear only accounted for 11% of U.S. energy generation at that point.

Going it alone: Though many U.S. adoption agencies had formerly banned single people from adopting children, a rise in the need for adoptive parents had prompted a change in policy, the Modern Living section reported. One qualification the ideal single adoptive parent would need, however, remained: “personal confidence in the face of possible dissent over what they are doing,” as one caseworker put it.

Great vintage ad: GE’s Christmas gift guide is a chance to see some of 1967’s top gadgets all in one place.

Coming up next week: Heart Transplants

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com