Besides capturing the last days of the British Empire, Homai Vyarawalla was one of the key visual chroniclers of the post-independence era, tracing the euphoria and disillusionments of a new nation as India’s first female photojournalist. For years her vast archive chronicling three decades of Indian history received less attention than the Indian work of her international contemporaries, Henri Cartier-Bresson and Margaret Bourke-White. But a new retrospective titled “Candid, The Lens and Life of Homai Vyarawalla” at Manhattan’s Rubin Museum of Art is finally paying tribute to her groundbreaking work.

Born in Navsari, Gujarat in 1913, Vyarawalla learned photography from her boyfriend Maneckshaw Vyarawalla. Her training at the Sir J. J School of the Arts, Mumbai influenced her pictorial sense as did the modernist photographs she got to see in second hand issues of LIFE magazine. Her early portraits of everyday urban life and modern young women in Mumbai show these influences, but since Vyarawalla was unknown and a woman, these were initially published in the Illustrated Weekly and Bombay Chronicle under Maneckshaw’s name.

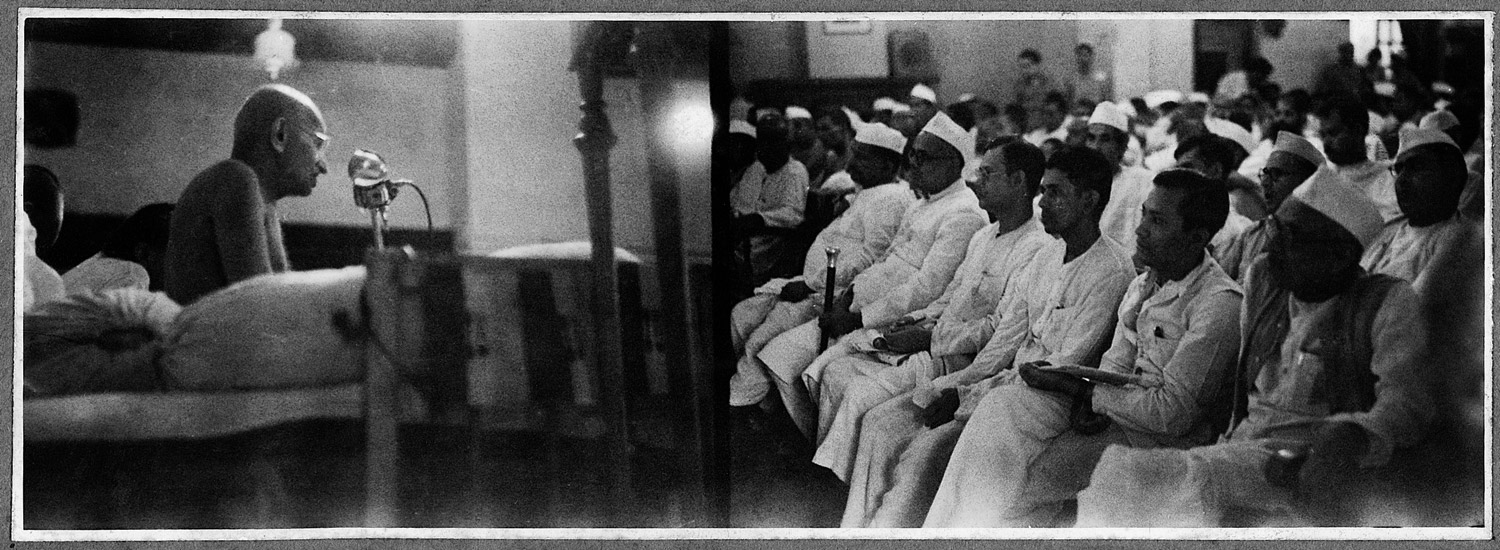

In 1942 Vyarawalla moved to Delhi to join the British Information Services. There she photographed a significant meeting when Congress members voted for the partition of India. Vyarawalla also documented the rituals of Independence, the building of dams and steel plants and the state visits of the most famous names in 20th-century history, including Mohammed Reza Shah Pahlavi, Martin Luther King, Jr., Ho Chi Minh, Marshall Tito and Russian leaders Brezhnev and Khruschev.

In 1956 Vyarawalla captured the first entry of a young Dalai Lama into India for TIME-LIFE. High-society magazines like Onlooker and Current requested her for “pictures of good looking women.” Not surprisingly, they published large spreads on the visits of Queen Elizabeth I and the fashionable U.S. First Lady Jackie Kennedy.

But Vyarawalla had a style of her own, too. Once, while waiting for Mrs. Kennedy to emerge for a photo shoot in 1962, a colleague of Vyarawalla whispered to the photographer: “She isn’t dressed properly as yet!” Though Vyarawalla was from the westernized Parsi community where women also wore dresses, she mostly dressed in a saree on assignment. Formal attire offered respectability in conservative times when she was the only woman among photographers. Her colleagues, many of them younger, nicknamed her “mummy.”

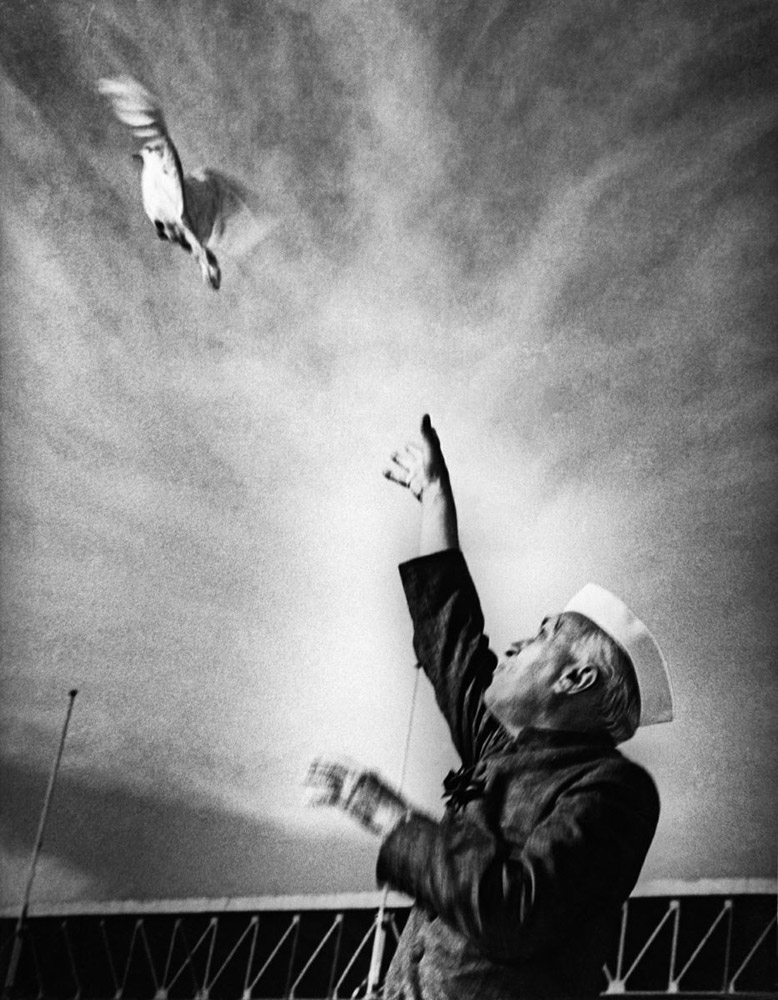

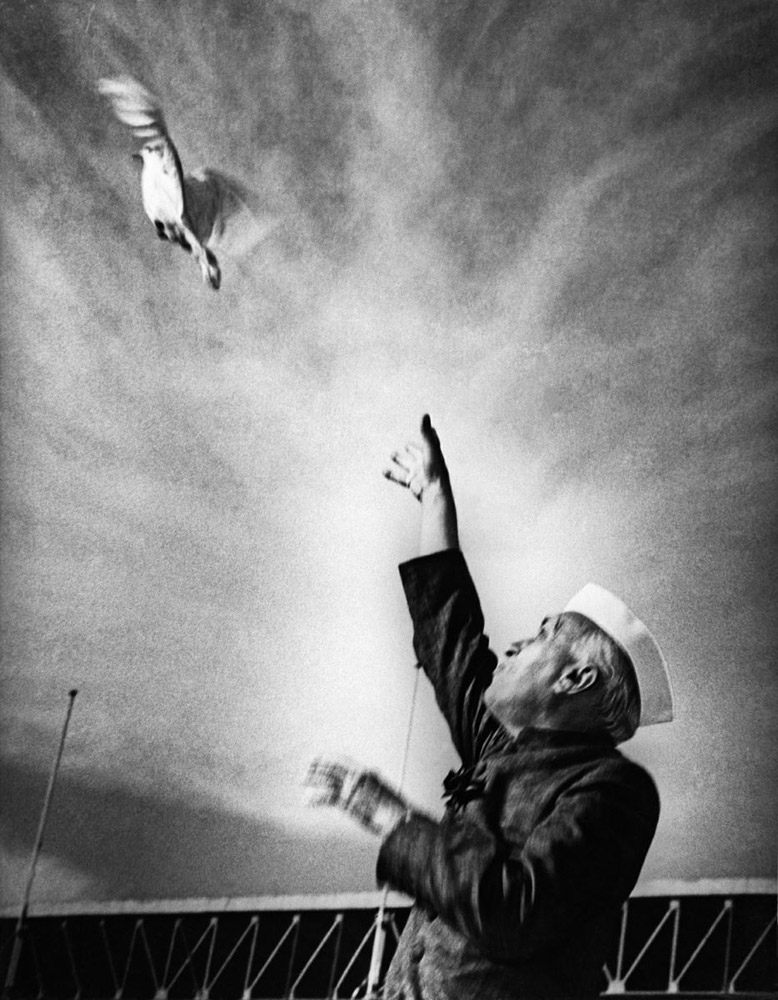

At a time when candid photography was favored, she got the best shots but was unobtrusive and respectful of the dignity of her subjects. She captured her favorite subject Jawaharlal Nehru, who was India’s first Prime Minister, in playful and vulnerable moments. Ironically, her most famous photographs of Gandhi were taken during his funeral in 1948. Vyarawalla loved black and white, and she processed her own images and believed that the choice of monochrome preserved them for posterity. And more than 50 years later, it’s easy to see why.

Candid, The Lens and Life of Homai Vyarawalla is on display at the Rubin Museum of Art in New York City through Jan. 14, 2013.

Sabeena Gadihoke is associate professor of video production at Jamia University in Delhi and is the author of Camera Chronicles of Homai Vyarawalla.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com