My dad was a little vain. Even at 80, he wore clothes with the ease of a man who had always been handsome and slim. When I was a kid, he would often wear ascots and tweedy jackets to drive me to work at the McDonald’s in the tiny rural town next to our tiny rural town. Dad had grown up with money and behaved as if that were still true, no matter how little we had at the time. This wasn’t always a good thing, but it was endless fodder for jokes.

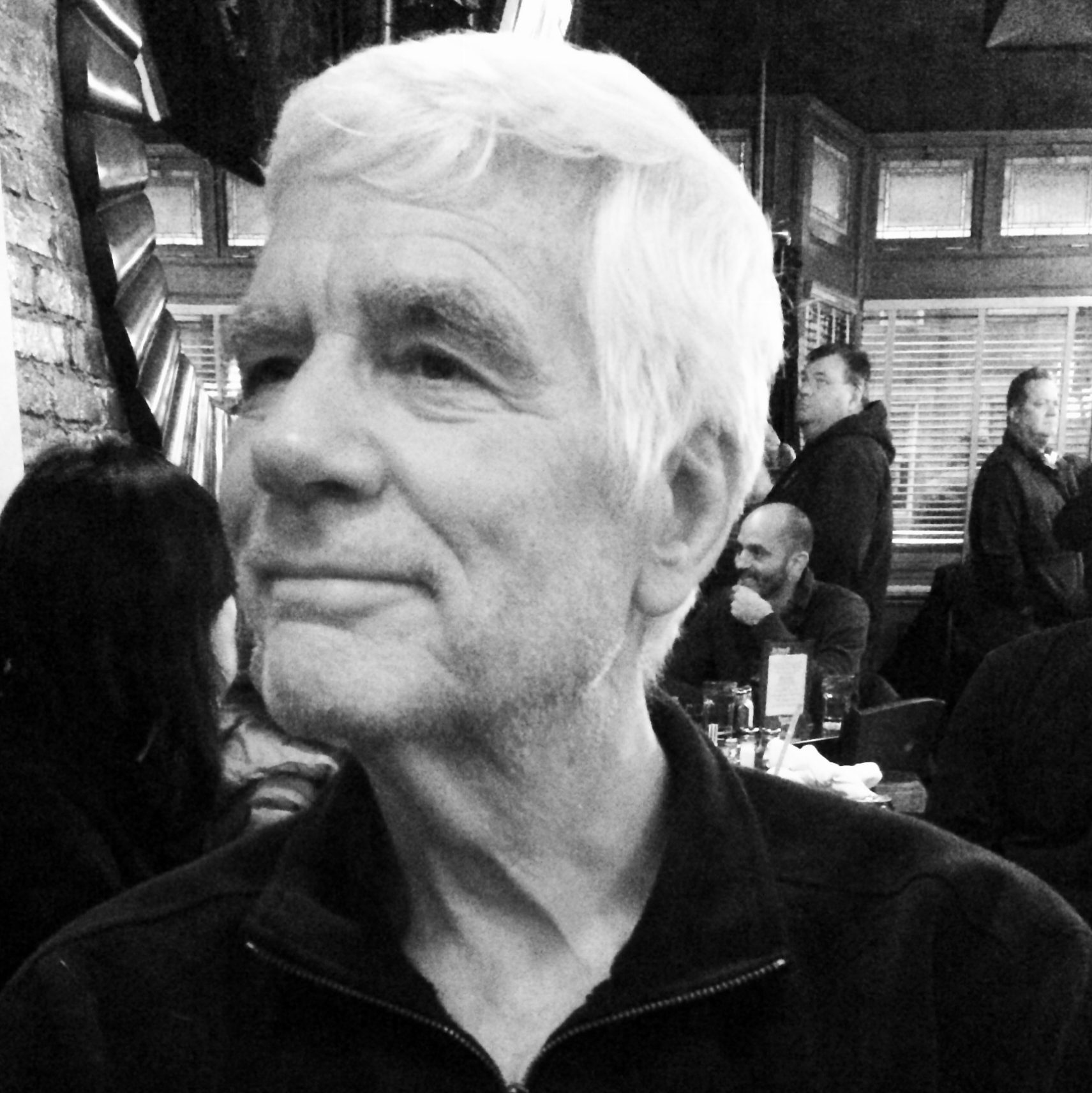

When we moved him into an assisted-living place near my apartment in Brooklyn, he introduced himself to every aide by bowing and pretending to kiss the tops of their hands. And because of dementia, he’d forget meeting them and do it all over again the next week with a flourish and his German accent. They loved him. He’d wander around the halls with his white hair combed, a bit unsteady even with a cane. It was as if he were always searching for the dining car on a European train.

This particular residence was pretty–the interior still had a bit of prewar elegance, much like Dad. But when I signed the papers guaranteeing the rent and extra “Memory Care,” he was already on borrowed time. Unless you’re particularly well resourced, anyone with an elderly parent knows the cruel math you have to do when choosing a nursing home or assisted-living residence. It goes something like this: personal savings plus Medicare, minus the level of disability, multiplied by the rate of decline.

That last variable is what gave me nightmares. Would he run out of money before he ran out of time? Most private homes don’t have to keep residents who just have Medicare, no matter how long they’ve lived there. If a parent is low on cash and getting less able, you have to look for a place that will provide even more care at less than half the price. There’s no way that equation adds up. Something has to be sacrificed, but what? Would it be the time to get him out of bed and into a chair? Or would it be the 30 extra minutes it now takes to feed him a whole meal?

I was a nursing-home aide in high school, and I know how hard it is just to do the basics–bathe, feed and change beds for everyone before the lunch trays come around. That math is tough on everyone: residents, aides and families. Well, everyone but the owners of these facilities, who are, thanks to forced arbitration clauses, often as unaccountable as they are hard to track down.

In Dad’s final year, there were dark hours when I wished pneumonia would take him before we had to take that last step of finding a nursing home. In the end, we had to. My sister spent months trying to locate a place that would take him. Hard enough for his generation, but if government predictions are correct, there will be such a shortage of caretakers when I’m 80 that no one knows how we’ll manage.

In that institutional hospital bed, Dad looked his age for the first time. He lasted there only a few months, and even that seemed too long to be in such a state. Surely, America, we can do better than this.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com