Heart treatments have improved vastly in recent years, but heart disease remains a leading killer of Americans. While researchers are constantly looking for ways to make current treatments better, a new study found that people with chest pain who receive stents — devices that open narrowed heart arteries — aren’t necessarily better off than people who don’t get them.

In a new study published in the Lancet, 200 people with chest pain were randomly assigned to either receive a stent, which requires a surgical procedure, or undergo a sham procedure in which the doctors only threaded a catheter through without inserting a stent. Six weeks later, they evaluated all of the people on a treadmill test. There were no significant differences in how much exercise the two groups could do, or in how much chest pain they reported.

While the study raises a lot of questions, heart experts say the results don’t mean stents aren’t safe. Here’s what you should keep in mind if you’re worried about getting a stent or already have one.

What is a heart stent?

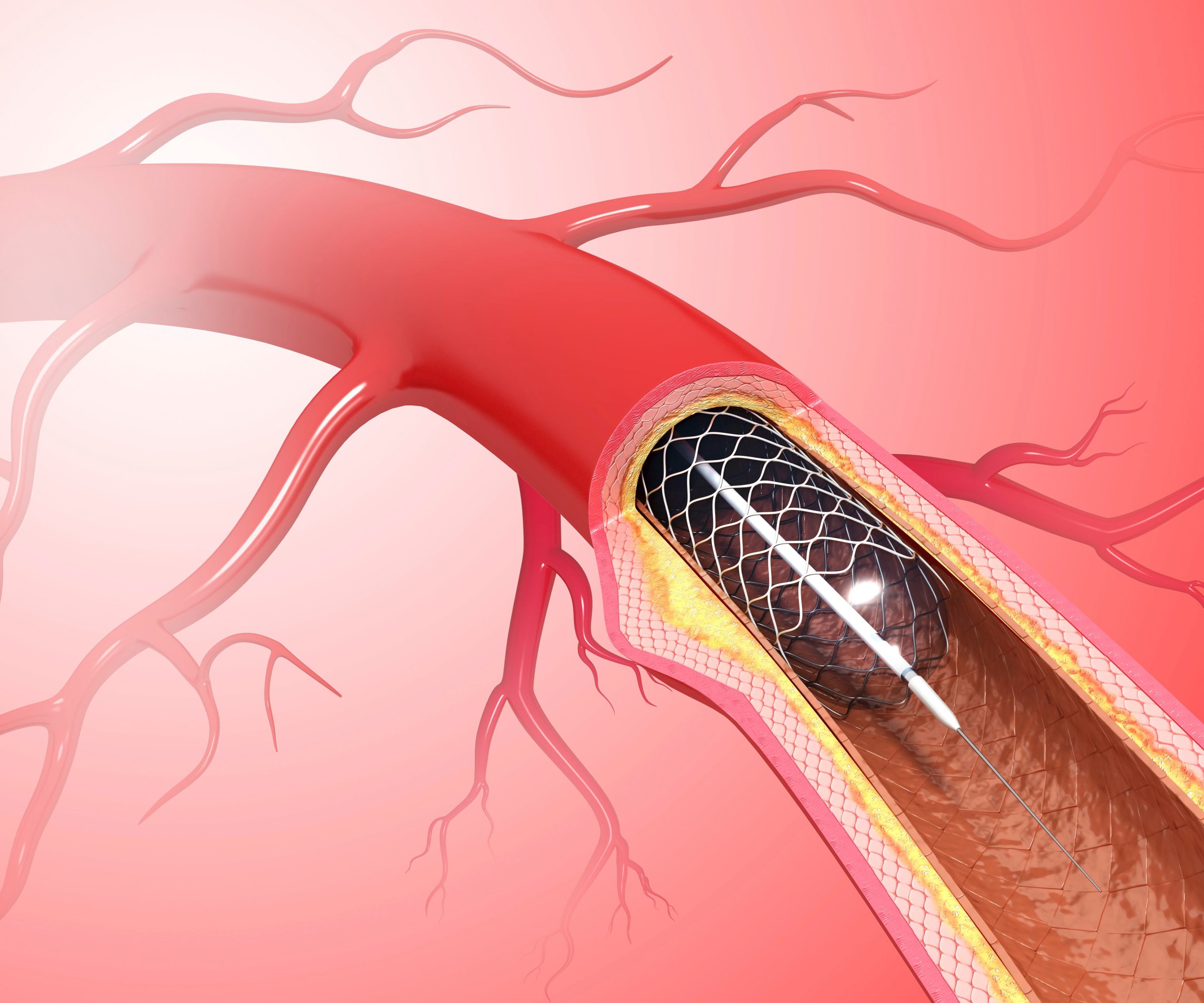

Stents are tiny mesh devices made of wire that doctors insert in narrowed heart arteries to prop them open. Stents can restore strong blood flow to the heart. For stent makers, it’s become a big business. Each year, half a million people get stents inserted to relieve chest pain or angina.

What is angina?

Angina is the medical term for chest pains that can occur when blood flow to the heart is compromised. Chest pains are usually caused by blood vessels in the heart that become narrowed and reduce the flow of blood to the heart.

Are heart stents dangerous?

Stents are relatively safe, especially if doctors carefully select the right people to get them.

The American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology do not recommend stents for all people who report chest pains. The groups advise doctors to evaluate how risky the chest pains are, and in most cases they suggest starting with medications to control cholesterol and blood pressure and blood vessel flexibility.

If the symptoms continue, or people can not tolerate the medications, then they discuss the possibility of having stents put in. In recent years, however, better medication and stricter guidelines on when stents are appropriate have reduced the number of people getting the devices.

“There was an era in medicine when stenting was used far too commonly and without consideration for their value as a medical therapy,” says Dr. Steven Nissen, chairman of the department of cardiovascular medicine at Cleveland Clinic. “But that era is gradually disappearing. Prudent physicians counsel their patients about all of their options and give the best medication therapy possible. When you do that, the number of people who actually need to have a stent is fairly modest.”

While the Lancet study found no significant differences between those with stents and those with them, Nissen points out that the treadmill test the researchers used to analyze the effect of the stents is subjective.

People may stop on the treadmill for a variety of reasons, not all of which have to do with whether they are experiencing chest pain, Nissen says.

While researchers also looked at other quality of life measures, 200 people is a relatively small number for such a study, and it’s hard to determine if the results are generalizable to bigger populations. So if you already have a stent, the results do not mean you should consider taking it out.

How do they put a stent in the heart?

Doctors make a small incision into the blood vessel in the groin and thread a thin flexible catheter from there to the heart. The catheter is equipped with a flat balloon at its tip. Once the tip reaches the vessel that’s narrowed, the balloon is inflated through the catheter, and the wire mesh stent pops open to keep the vessel open. Most people leave the hospital 12 to 24 hours after the procedure, and can return to work a few days later.

How long do stents last?

Theoretically, stents are made to last for as long as the person who has them, but some do get blocked up again. If that happens, doctors can remove the stent and insert another, or do bypass surgery to bypass the artery altogether.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com