According to an old French saying, translations are like women: when they are beautiful, they are not faithful; when they are faithful, they are not beautiful. This witticism, which works better in French because it rhymes — belles… fidèles — may not seem very funny, but it points to a pair of questions that were particularly pressing in 18th century France. First, what was the value of ancient Greek and Roman literature, if any, in the wake of contemporary scientific and philosophical advances? Secondly, what was the value of women in a society where, though a few had proved their ability to keep up with intellectual and scholarly conversations, women were still often seen as the second sex?

Anne Dacier (née Lefèbvre), who translated The Odyssey into French prose in 1716, among other major classical translation projects (including an Iliad in 1712), was a staunch defender of the value of antiquity, and she argued that her versions of classical literature were more accurate than the “faithless beauties” (les belles infidèles) of her male predecessors. By insisting on her own “fidelity,” she was perhaps trying to dispel malicious gossip about her personal life; posthumous and unfounded accounts of her life (by men) claimed that she defended Homer’s adulterous Helen because of her own eagerness to abandon her first husband. Her insistence on her own philological “fidelity” also bolstered her authority — an important project for the lone classical “translator-ess” (as she was called: traductrice) in a world of male writers and intellectuals.

Some 300 years later, as the translator behind the first published English version of The Odyssey by a woman, I look back to my French predecessor with respect and admiration. Like her, I believe that in important ways, my version of the poem is more faithful than the dozens of earlier English translations by men. But I am also deeply suspicious of the imagery by which translations are praised for being “faithful,” and their attractiveness is assumed to be in inverse proportion to their accuracy. We tend not to think hard enough about what it means for a translator to keep faith. Early translators of the Christian Bible saw their work as an expression of their faith in God, but Jerome famously insisted (in his Letter 57) that his translation “by sense for sense, not word for word” was not a sign of infidelity – as his detractors claimed – but instead marks his willingness to communicate the meaning of the original.

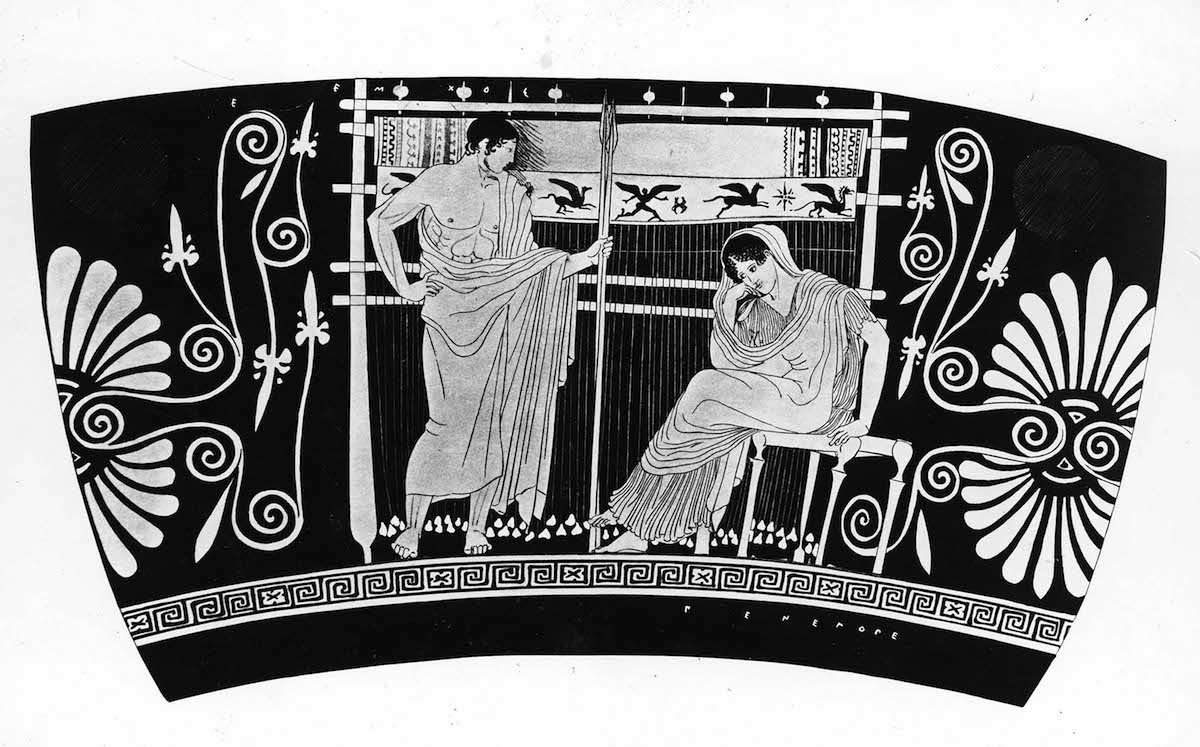

For a translator of The Odyssey, the term “fidelity” takes on a different resonance, since the poem itself is so deeply engaged with questions of loyalty, fidelity and truth – which turn out to mean entirely different things for male and female characters. Odysseus tells elaborate lies to achieve his goals, whereas Penelope deceives her suitors silently, by undoing her own work. In terms of sexual loyalty, Penelope is praiseworthy because she waits and weeps for 20 years, while her husband’s affairs and flirtations are presented as perfectly acceptable. Female characters are obstacles to the male protagonist’s mission (like the man-eating Scylla, the man-swallowing Charybdis, the man-seducing Sirens, the man-transforming Circe and the man-trapping Calypso) or helpers like Athena and Nausicaa, who aid Odysseus with a little help from their fathers. We are invited to celebrate the male hero’s success in evading bewitching females and foreign monsters, reaching his homeland, outwitting and slaughtering his male rivals, and regaining control of his property (including his slaves, at least those who survive his homecoming), and his subordinate wife.

But the poem also provides glimpses of alternative perspectives. Helen, the adulterous wife whose affair with Paris sparked the Trojan War, is a surprisingly well-rounded and likable character, as is Calypso, who complains quite reasonably about the sexual double standards that operate in the world of Mount Olympus. Penelope’s vivid accounts of her dreams allow us to see the gap between her world-view and experiences and those of her husband. And the poem shows us the desperate pain and shock of the murdered slave women who are killed for having slept with the suitors.

Translators interpret a poem’s depiction of gender — or any other concept — in light of their own presuppositions. For example, Robert Fagles’ still top-selling version of The Odyssey, was praised by Garry Wills in the New Yorker when it came out in 1996 for being “politically correct” and for its “sympathetic” treatment of female characters. But when we look closer, Fagles’ translation is most generous in its attitude to the elite female characters, especially Penelope and Nausicaa. By contrast, in the deeply disturbing moment when Odysseus’ son Telemachus hangs the slave women who have been sleeping with the suitors, Fagles has Telemachus call them “sluts” and “the suitors’ whores.” Other translators use similar terms: Richmond Lattimore labels the victims as “creatures,” and Stanley Lombardo calls them “the suitors’ sluts.” But there is nothing in Homer in this passage to correspond to the modern pseudo-moral judgments of words like “sluts,” “whores” or “creatures.” We may be tempted to assume that ancient texts will articulate benighted ideas that “we” have now risen above; but this is a clear case where modern bias has been projected back onto antiquity. My Telemachus says that the women “lay beside the suitors.”

Is the point simply to say that one version is straightforwardly more faithful than another? Not quite, since all translations involve a process of interpretation; the metaphor of “fidelity” itself tends to limit our understanding of what a translation is and can do. Moreover, “fidelity,” especially for women, implies a narrowly singular kind of loyalty. By contrast, terms like “truth” or “responsibility” do not imply a passive submission to a singular authority. As a translator, I aim to be responsible to my own readers and to the English language, as well as to the language of Homer, and to the original poem’s ethical complexity as well as its literary form. I hope to be, like Odysseus himself, a flexible, strategic person “of many turns.” I think of myself not as Homer’s patient, loyal, tear-stained and silent wife, but as his host or his guardian goddess, enabling him to assume a new guise and tell his story again, in a strange foreign land.

Emily Wilson, whose translation of The Odyssey is available this week, is a professor of classical studies and chair of the Program in Comparative Literature and Literary Theory at the University of Pennsylvania.

Correction: The original version of this article misstated the name of the woman who translated The Odyssey into French in 1716. Her married name was Anne Dacier, not Anne Lefèbvre.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com