It’s challenging enough to make a comfortable life for yourself. How much are you supposed to care about the welfare of others, particularly people who have fallen through society’s cracks?

There’s no measurable answer to that question. Which is perhaps why, in wrestling with it, Swedish director Ruben Ostlund’s caustically elegant satire The Square has no real ending. It does, however, have a beginning and quite a few terrific middles. The picture, winner of this year’s Palme d’Or at Cannes, is ambitious and frustrating, teasing us into wanting to know exactly where it’s going, only to slip away with a final shot that’s barely a whisper. Yet its seductiveness is sublime. Instead of making you think–a tack that never works anyway–its way of thinking trails you, devilishly, out of the theater. It’s a trickster in movie form.

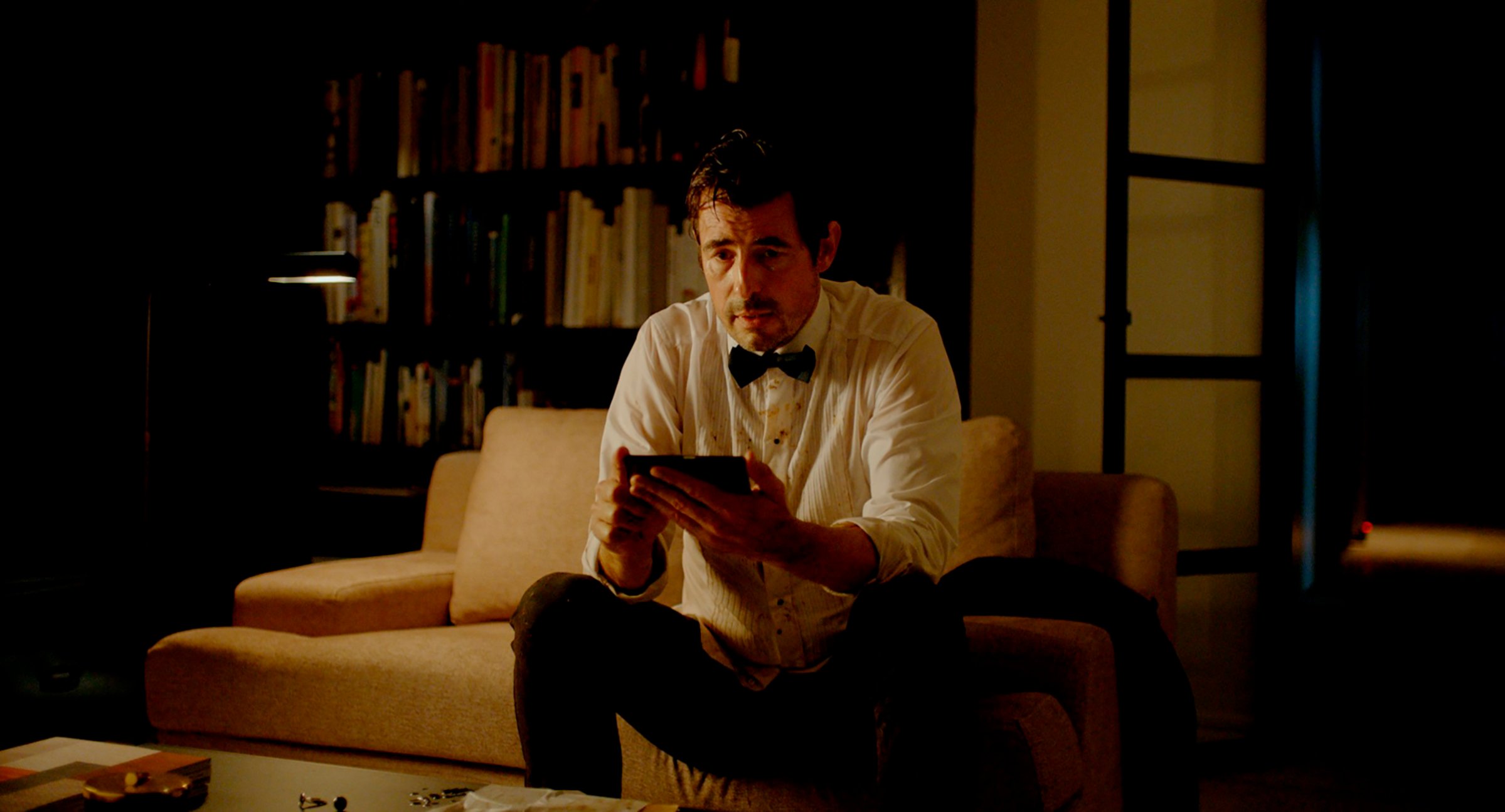

Danish actor Claes Bang plays Christian, the suave, 50-ish chief curator of a Stockholm museum dedicated to out-there art. This tony institution is gearing up for a new exhibit, “The Square,” whose chief feature is a strict arrangement of cobblestones accompanied by a plaque that reads, in part, The Square is a sanctuary of trust and caring. The exhibit is an invitation to ponder the nature of the social contract, and how on earth does an institution sell that?

Meanwhile, Christian faces a jumble of complicated work and personal affairs. After he helps a stranger on the street, he learns that his wallet, phone and cuff links have been expertly lifted. His quest to get his stuff back leads him to a low-income building in a part of town that’s not nearly as nice as the one he lives in, and, eventually, to an angry young boy who sees everything that’s hypocritical about him long before he does. Christian also navigates a chancy and sometimes hilarious liaison with an American journalist (a dazzling, rapturously offbeat Elisabeth Moss), whose demands throw him off his game.

The Square wouldn’t work without an actor as dashing and appealing as Bang is: with his great, mildly snaggletoothed smile, he makes Christian’s numbness both funny and pathetic. This movie is more sprawling than Ostlund’s last feature, the superb 2014 Force Majeure, but he’s still an engaging mischief-maker. The title may in fact be a winking work of nonrepresentational art itself. A square has a defined border. The movie Ostlund has made is adamantly open-ended. There are no right angles and no right answers.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com