As her husband lay moaning in pain from the cancer riddling his body, Patricia Martin searched frantically through his medical bag, looking for a syringe.

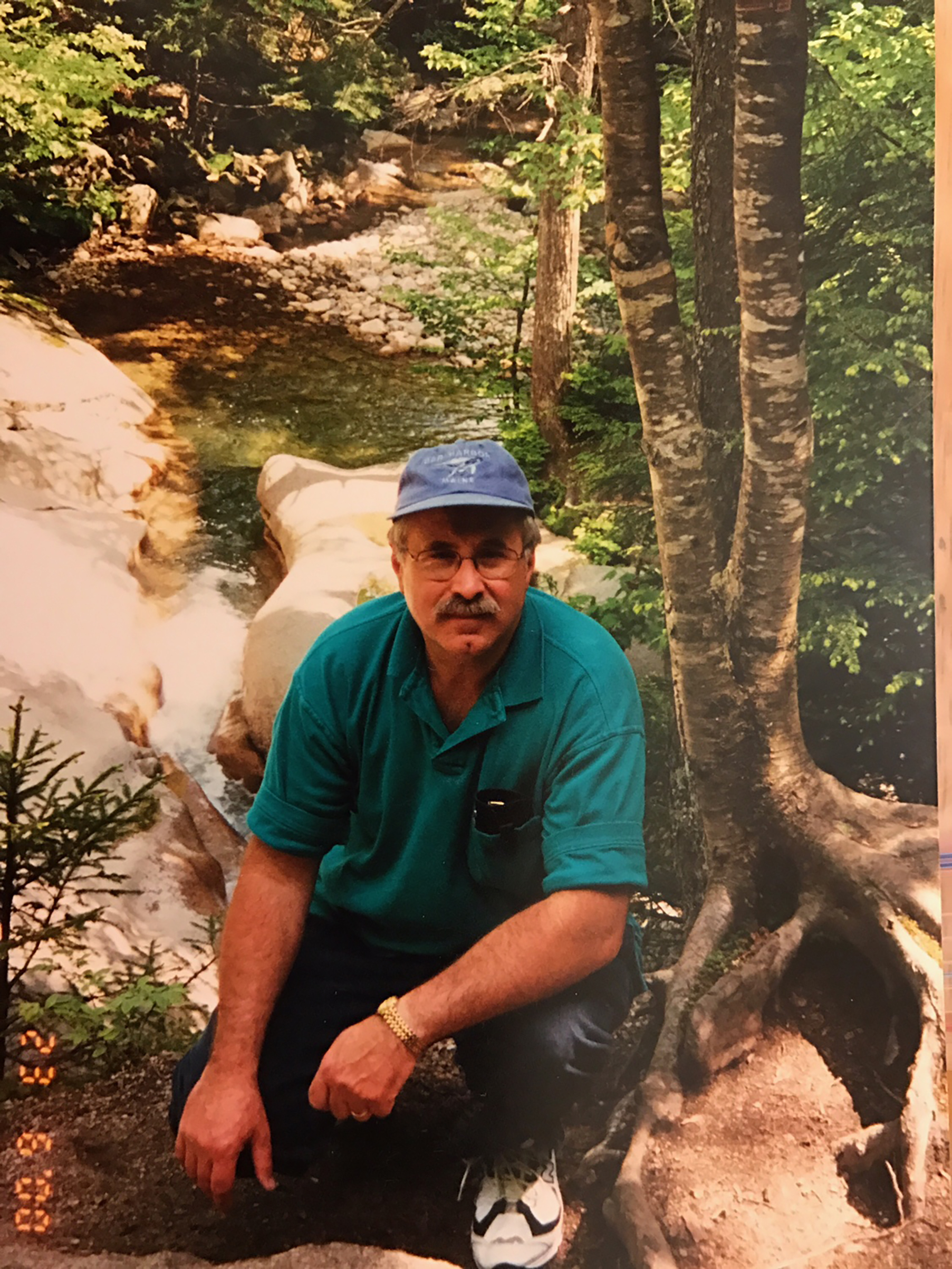

She had already called the hospice twice, demanding liquid methadone to ease the agony of Dr. Robert E. Martin, 66. A family practice physician known to everyone as “Dr. Bob,” he had served the small, remote community in Wasilla, Alaska, for more than 30 years.

But the doctor in charge at Mat-Su Regional Home Health and Hospice wasn’t responding. Staff said he was on vacation, then that he was asleep. Martin had waited four days to get pain pills delivered, but her husband could no longer swallow them. Now, they said, she should just crush the drugs herself, mix them with water and squirt the mixture into his mouth. That’s why she needed the syringe.

“I thought if I had hospice, I would get the support I needed. They basically said they would provide 24/7 support,” she said, still shaking her head in disbelief, three years later. “It was a nightmare.”

Patricia had enrolled her husband in hospice when the metastatic prostate cancer reached his brain, expecting the same kind of compassionate, timely attention he had given his own patients. But Bob Martin had the misfortune to require care during a long holiday weekend, when hospices are often too short-staffed to fulfill written commitments to families. The consequences, as documented through a review of official records and interviews, were dire.

It took six days and three more calls before he received the liquid methadone he needed. Hospice denied Patricia Martin’s requests for a catheter, and she and her son had to cut away his urine-soaked clothing and bedding, trying not to cause him additional pain. The supervising hospice doctor never responded. A nurse who was supposed to visit didn’t show up for hours, saying she was called for jury duty.

Bob Martin died just after midnight on Jan. 4, 2014. “It was just sheer chaos,” Patricia Martin said. “It makes me wonder about other people in this situation. What happens to them?”

The Martins had entrusted the ailing doctor’s final days to one of the nation’s 4,000-plus hospice agencies, which pledge to be on call around the clock to tend to a dying person’s physical, emotional and spiritual needs. It’s a thriving business that served about 1.4 million Medicare patients in the U.S. in 2015, including over a third of Americans who died that year, according to industry and government figures.

Yet as the industry has grown, the hospice care people expect — and sign up for — sometimes disappears when they need it most. Families across the country, from Appalachia to Alaska, have called for help in times of crisis and been met with delays, no-shows and unanswered calls, a Kaiser Health News investigation published in cooperation with TIME shows.

The investigation analyzed 20,000 government inspection records, revealing that missed visits and neglect are common for patients dying at home. Families or caregivers have filed over 3,200 complaints with state officials in the past five years. Those complaints led government inspectors to find problems in 759 hospices, with more than half cited for missing visits or other services they had promised to provide at the end of life.

The reports, which do not include victim names, describe a 31-year-old California woman whose boyfriend tried for 10 hours to reach hospice as she gurgled and turned blue, and a panicked caregiver in New York calling repeatedly for middle-of-the-night assistance from confused hospice workers unaware of who was on duty. In Michigan, a dementia patient moaned and thrashed at home in a broken hospital bed, enduring long waits for pain relief in the last 11 days of life, and prompting the patient’s caregiver to call nurses and ask, “What am I gonna do? No one is coming to help me. I was promised help at the end.”

Only in rare cases were hospices punished for providing poor care, the investigation showed.

Six weeks after Martin died, his wife filed a complaint against Mat Su Regional with the Alaska Department of Health and Social Services. The agency’s investigation concluded that the hospice failed to properly coordinate services, jeopardizing his end-of-life care. Hospice officials declined interview requests for this story.

Hospice is available through Medicare to critically ill patients expected to die within six months who agree to forego curative treatment. The care is focused on comfort instead of aggressive medical interventions that can lead to unpleasant, drawn-out hospital deaths. The mission of hospice is to offer peaceful, holistic care and to leave patients and their loved ones in control at the end of life. Agencies receive nearly $16 billion a year in federal Medicare dollars to send nurses, social workers and aides to care for patients wherever they live. While the vast majority of hospice is covered by Medicare, some is paid for by private insurance, Medicaid and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

To get paid a daily fee by Medicare, hospice agencies face many requirements. They must lay out a plan of care for each patient, ensuring they’ll treat all symptoms of the person’s terminal illness. And they’re required to be on call 24/7 to keep patients comfortable, but because each patient is different, there’s no mandate spelling out how often staff must show up at the home, except for a bimonthly supervisory visit. Hospices must stipulate in each patient’s care plan what services will be provided, when, and by whom, and update that plan every 15 days. Hospices are licensed by state health agencies, and subject to oversight by federal Medicare officials and private accreditation groups.

Although many people think of hospice as a site where people go to die, nearly half of hospice patients receive care at home, according to industry figures.. At its best, hospice provides a well-coordinated interdisciplinary team that eases patients’ pain and worry, tending to the whole family’s concerns. For the 86% of Americans who say they want to die at home, hospice makes that increasingly possible.

But when it fails, federal records and interviews show it leaves patients and families horrified to find themselves facing death alone, abandoned even as agencies continue to collect taxpayer money for their care.

On duty, but unreachable

In St. Stephen, Minn., Leo D. Fuerstenberg, 63, a retired U.S. Veterans Affairs counselor, died panicked and gasping for air on Feb. 22, 2016, with no pain medication, according to his wife. Laure Fuerstenberg, 58, said a shipment sent from Heartland Home Health Care and Hospice included an oxygen tank, a box of eye drops and nose drops, but no painkillers.

“They were prescription drugs, but it didn’t say what they were or how to give them,” she recalled. “I just panicked. I called the hospice, and I said, ‘We’re in trouble. I need help right away.’ I waited and waited. They never called back.”

For more than two hours, she tried desperately to comfort her husband, who had an aggressive form of amyloidosis, a rare disease that can lead to organ failure. But he died in her arms in bed, trapping her under the weight of his body until she managed to call neighbors for help.

“That last part of it was really horrible,” she said. “The one thing I promised him is that he wouldn’t be in pain, he wouldn’t suffer.”

Later, state investigators determined that Heartland’s on-duty hospice nurse had muted her phone, missing 16 calls for help. Hospice officials did not respond to repeated interview requests.

“They never followed their protocol, and I’ve never had anybody from there say, ‘We failed, We were wrong,’” said Fuerstenberg, a school counselor who said she relives her husband’s death daily. “If that had been me on my job, I’d be fired.”

Her account was among more than 1,000 citizen complaints that led state investigators across the country to uncover wrongdoing from January 2012 to February 2017, federal records show.

But the complaints offer only a glimpse of a larger problem, said Dr. Joan Teno, a researcher at University of Washington who has studied hospice quality for 20 years. “These are people who got upset enough to complain.”

Officials with the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO), an industry trade group, said that such accounts are inexcusable — but rare.

“I would venture to say whatever measure you want to use, there are an exponential number of positive stories about hospice that would overwhelm the negative,” said Jonathan Keyserling, NHPCO’s senior vice president of health policy. “When you serve 1.6 million people and families a year, you’re going to have instances where care could be improved,” he added.

But even one case is too many and hospices should be held accountable for such lapses, said Amy Tucci, president and chief executive of the Hospice Foundation of America, a nonprofit focused on education about death, dying and grief. “It’s like medical malpractice. It’s relatively rare, but when it happens, it tarnishes the entire field,” she said.

How often hospices fail to respond to families or patients is an understudied question, experts say, in part because it’s hard to monitor. But a recent national survey of families of hospice patients suggests the problem is widespread: 1 in 5 respondents said their hospice agency did not always show up when they needed help, according to the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) Hospice Survey, designed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

“That’s a failing grade,” Teno said. “We need to do better.”

‘It’s like they just didn’t do anything’

Hospice care in the U.S. got its start in the 1970s, driven by religious and non-profit groups aimed at providing humane care at the end of life. Today, however, many providers are part of for-profit companies and large, publicly traded firms. It’s a lucrative business: For-profit hospices saw nearly 15% profit margins on Medicare payments in 2014, according to the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission.

Most families are happy with their experience, according to the CAHPS survey. In data collected from 2015 to 2016 from 2,128 hospices, 80% of respondents rated hospice a 9 or 10 out of 10. Kaiser Family Foundation polling conducted for this story found that out of 142 people with hospice experience, 9% were “dissatisfied” and 89% “satisfied” with hospice. (Kaiser Health News is an editorially independent project of the foundation.)

Indeed, many people give hospice glowing reviews. Lynn Parés, for instance, gushed about her experience from 2013 to 2014 with Family Hospice of Boulder, Colo. When her 87-year-old mother cut her leg, staff came daily to treat her wound. In her last week of life, a nurse came every day. The hospice also provided family counseling, spiritual guidance, and volunteers who surrounded her mother’s bedside, singing old-time songs.

“They were in constant contact with us,” Parés said of the hospice. “It’s amazing to me how much heart there is involved in hospice care.” After her mother died, Parés and her siblings donated part of their inheritance to the hospice. “I can never say enough good about them.”

In 2015, the small, family-owned Boulder company was acquired by a large regional chain, New Century Hospice, part of a larger wave of consolidation in the field.

As the industry grows — hospice enrollment has more than doubled since 2000 — some companies are not following through on their promises to patients, according to the government reports. For instance, data show many hospices fail to provide extra care in times of crisis. To get Medicare payments, hospices are required to offer four levels of care: routine care, which is by far the most common; respite care to give family caregivers a break for short time periods; and two levels of so-called “crisis care,” continuous care and general inpatient care, when patients suffer acutely. But 21% of hospices, which together served over 84,000 patients, failed to provide either form of crisis care in 2015, according to CMS.

Other research has found troubling variation in how often hospice staff visit when death is imminent. A patient’s final two days of life, when symptoms escalate, can be a scary time for families. Teno and her co-authors found that 281 hospice programs, or 8.1% of hospices, didn’t provide a single skilled visit — from a nurse, doctor, social worker or therapist — to any patients who were receiving routine home care, the most common level of care, in the last two days of life in 2014.

Regardless of how often they visit, hospices collect the same flat daily rate from Medicare for each patient receiving routine care: $191 for the first 60 days, then $150 thereafter, with geographic adjustments as well as extra payments in a patient’s last week of life.

Overall, 12.3% of patients on routine home care received no skilled visits in the last two days of life, the study found. Patients who died on a Sunday had the worst luck: they were more than three times less likely to have a skilled visit than those who died on a Tuesday. Teno said that gives her a strong suspicion that missed visits stem from chronic understaffing, since hospices often have fewer staff on weekends.

In Minnesota, Fuerstenberg’s pleas for help went unanswered on a Sunday evening; her husband died just after midnight on Monday. She was appalled when she received a bill for care the agency said occurred on that day.

“When they got paid for nothing, it was like a slap in the face,” said Fuerstenberg, who filed a complaint with Minnesota health officials last year. She heard nothing about the case from hospice officials and didn’t learn it had been investigated until she was contacted by reporters for this story.

In St. Paul, Virginia, a small town in the Appalachian mountains, Virginia Varney enlisted Medical Services of America Home Health and Hospice, a national chain, to care for her 42-year-old son, James Ingle, who was dying of metastatic skin cancer. On his final day, Christmas of 2012, he was agitated, vomiting blood, and his pain was out of control. Varney called at least four times to get through to hospice. Hours later, she said, the hospice sent an inexperienced licensed practical nurse who looked “really scared” and called a registered nurse for backup. The RN never came. Ingle died that night.

Varney said she felt numb, angry and “very disappointed” in the hospice care: “It’s like they just didn’t do anything. And I know they were getting money for it.”

“They told me 24 hours a day, seven days a week, holidays and all,” Varney said. “I didn’t find that to be true.”

An investigation by Virginia state inspectors, which corroborated Varney’s story, revealed the hospice nurse changed the records from that night after the fact, altering the time she reported being at the home. The registered nurse was fired that February. The hospice declined to comment for this story.

A problem with few solutions

Just how often are hospice patients left in the lurch? Inspection reports, performed by states and collected by CMS, don’t give a clear answer, in part because hospices are reviewed so infrequently.

Unlike nursing homes, hospices don’t face inspection every year to maintain certification. Based on available funding, CMS has instead set fluctuating annual targets for state hospice inspections. In 2014, CMS tightened the rules, requiring states to increase the frequency to once every three years by 2018.

Often, promising to do better is the only requirement hospices face, even when regulators uncover problems. The Office of the Inspector General at the federal Department of Health and Human Services has called for stricter oversight and monitoring of hospice for a decade, said Nancy Harrison, a New York-based deputy regional inspector general. One problem, she said, is there is no punishment short of termination — barring the hospice from receiving payment from Medicare— which is disruptive for dying patients who lose service.

CMS records show termination is rare. Through routine inspections as well as those prompted by complaints, CMS identified deficiencies in more than half of 4,453 hospices from Jan. 1, 2012 to Feb. 1, 2017. During that same time period, only 17 hospices were terminated, according to CMS.

In Alaska, Patricia Martin filed a complaint against Mat-Su Regional with the Alaska Department of Health and Social Services six weeks after her husband’s death. An investigation concluded that the hospice failed to properly coordinate services, jeopardizing his end-of-life care. Hospice officials declined to comment about his case, citing patient privacy rules. In an email, Mat-Su administrator Bernie F. Jarriel Jr. said the hospice “strengthened our policy and procedures” as a result of the investigation, and “members of our caregiving team have been re-educated on these practices.”

In Minnesota, officials with the local Heartland Home Health and Hospice agency referred questions to its corporate owner, HCR ManorCare of Toledo, Ohio. Officials there did not respond to multiple requests for comment about Leo Fuerstenberg’s care. CMS documents indicate the nurse who missed 16 messages “was re-educated on responsibilities of being on call.”

In a 2016 study, the OIG’s Harrison and colleagues called for state surveyors to better scrutinize the care plans hospices outline for their patients. And they recommended that CMS create a range of different levels of punishment for hospice infractions, such as requiring in-service training, denying payments, civil fines, and imposing temporary management.

CMS has no statutory authority to impose those alternate sanctions, said spokesman Jibril Boykin. But it did work to increase transparency in August by launching a consumer-focused website called Hospice Compare that now includes hospices’ self-reported performance on quality measures, and, next year, will include family ratings of hospices.

Until that happens, there’s little information available for families trying to pick a hospice that will show up when it counts. Tucci, of the Hospice Foundation of America, suggests that families of ill or frail relatives consider hospice options before a crisis occurs. The agency recommends 16 questions families should ask before choosing a hospice.

Back in Alaska, Patricia Martin said she’s still waiting for officials with Mat-Su Regional Home Health and Hospice to answer questions about her husband’s poor care. She urges other families enrolling patients in hospice to be vigilant.

“It is my hope that no other family or patient will ever have to go through the nightmare that we did,” she said. “If they promise you they’re going to do something, they should do it.”

This story was produced in collaboration with Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation. JoNel Aleccia and Melissa Bailey are Kaiser Health News reporters

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly described the drug Patricia Martin requested from hospice. It was liquid methadone, not liquid morphine.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com