An unusual medical case gives new meaning to the phrase blood, sweat and tears.

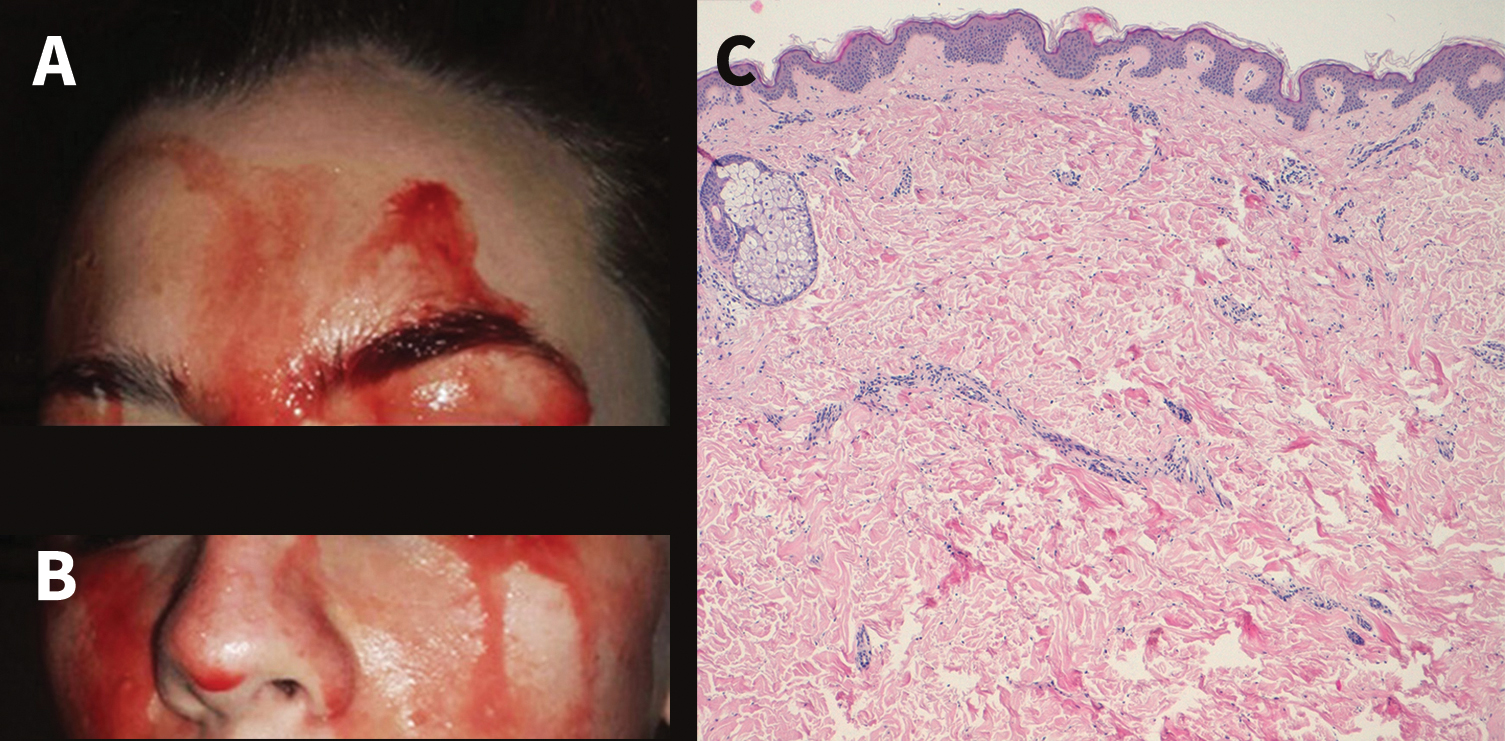

According to a case study published Monday in the Canadian Medical Association Journal, a 21-year-old Italian woman checked into a medical ward complaining of a strange—and horrifying—symptom: She had been bleeding intermittently from her face and palms for three years, seemingly without cause. She had no visible broken skin, and bleeding episodes sometimes began without warning, though they often intensified during times of stress. The woman had become socially isolated as a result of the condition.

Though doctors treated her for symptoms of major depressive disorder and panic disorder, the woman’s physical exams came back normal. Still, the bleeding persisted. Eventually, her doctors reached a rare—and somewhat controversial—diagnosis: hematohidrosis, or “blood sweating.” She was treated with propranolol, a beta-blocker that’s commonly used to regulate blood pressure and heart rate, and while her bleeding didn’t stop entirely, the treatment did lead to a “marked reduction” in symptoms, according to the article.

In cases of hematohidrosis, blood seeps out of unbroken skin, just as sweat normally does. It’s most common on the face, ears, nose and eyes, according to the National Institutes of Health Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center, and it’s often associated with fear and emotional stress. Some people with the condition even cry bloody tears.

Hematohidrosis is extremely rare, but it’s nothing new. The Bible mentions Jesus sweating blood, and observed cases date way back to the third century B.C., according to medical historian and hematologist Jacalyn Duffin, who wrote a commentary that accompanied the new article. Nonetheless, there’s still a lot doctors don’t know about hematohidrosis—including why it happens. There’s so much uncertainty, in fact, that some doctors don’t believe it’s a valid diagnosis. Even the article notes that “there is no single explanation of the source of bleeding,” and that the current hypothesis—that blood passes through sweat glands due to “abnormal constrictions and expansions” of nearby blood vessels—has not been definitively proven.

Duffin believes that the condition is real, if misunderstood. “Ironically, for an increasingly secular world, the long-standing association of hematohidrosis with religious mystery may make its existence harder to accept,” she writes. “It seems that humans do sweat blood, albeit far less often literally than metaphorically.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- 22 Essential Works of Indigenous Cinema

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Jamie Ducharme at jamie.ducharme@time.com