The following is an excerpt from the new updated and expanded edition of TIME: The Illustrated History of the World’s Most Influential Magazine:

In 1937, five years before the United States fully joined World War II, an editor who would be key in developing the TIME cover school joined the magazine. His name was Dana Tasker, a professional who had studied literature and English at Amherst College with poet Robert Frost. He came from teaching art history at Deerfield Academy and working as visual and text editor at Reader’s Digest and Newsweek.

Tasker’s first job at TIME was as editor of the “Business & Finance” section, but he then devoted himself specifically to reorganizing the art department in general, and covers, illustrations and graphics in particular.

The first challenge Tasker faced during his tenure was finding cover illustrations that were less predictable. (At the time, the images on the magazine’s main page — photos or charcoal drawings — were usually black and white, which diminished their impact. In 1940, for instance, only nine of the 53 covers published were four-color images). He also lost sleep over the question of whether the selected newsmakers should be portrayed as they were physically, or interpreted by the magazine’s illustrators and editors?

To solve all these issues, during his tenure, Tasker hired a group of illustrators who were fundamental in the development of TIME‘s cover school. With them, Tasker was able to move forward with what is considered to be one of his big contributions to magazine covers: the creation of the “news illustration” or “news portrait.” Those were the designations given to the art that included the newsmaker’s face, with a background that complemented, clarified and contributed to the facts that had led to featuring the personality on the magazine’s cover. The basis of the formula was to portray a “meticulously realistic painted likeness [to the newsmaker] complemented by background[s] and symbols alluding to the reason for the subject[’s] newsworthiness,” according to Frederick S. Voss, in his book Faces of Time: 75 Years of Time Magazine Cover Portraits.

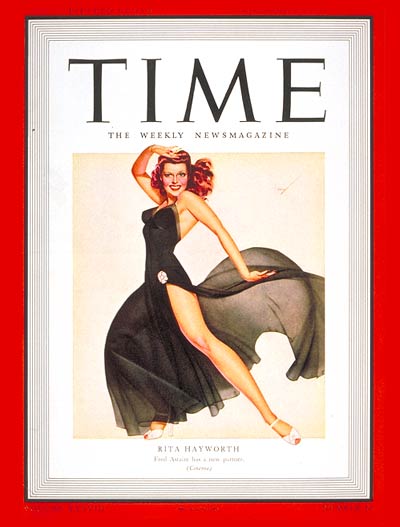

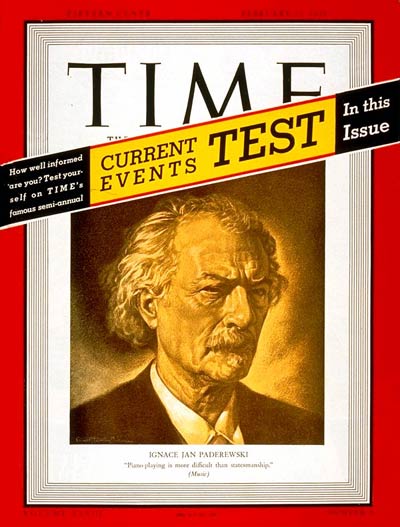

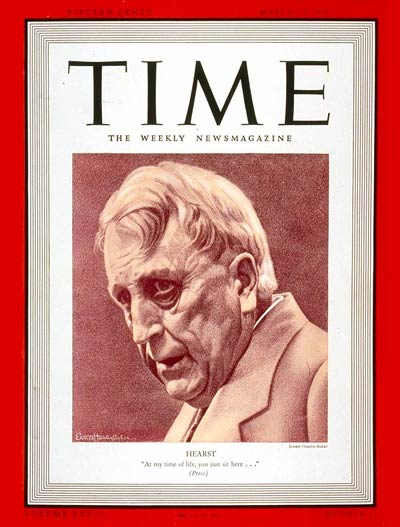

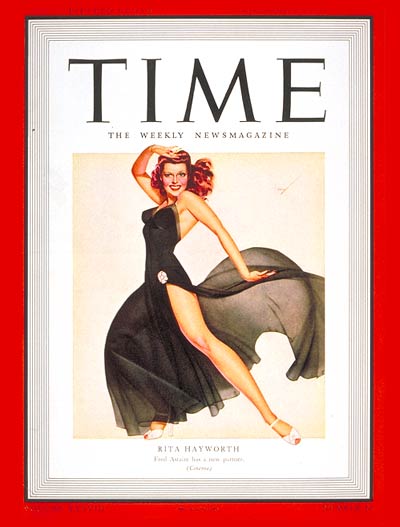

Among the images that started to characterize this new cover style in 1939 and 1940 were those Ernest Hamlin Baker made of Polish pianist Ignace Paderewski, American journalism magnate William Hearst and German pastor Martin Neimoller. However, Tasker’s style first made a splash with the Nov. 10, 1941, issue, when the magazine cover featured Rita Hayworth’s full body. At the time, she was Hollywood’s best-known sex symbol. Illustrator George Petty’s depiction of Hayworth, wrapped in a black diaphanous dress with a slit revealing her beautiful and curvaceous leg, graced the cover, provoking both positive and negative comments. But more than anything, it made clear that new changes were taking place on the magazine’s covers. They would become even more prominent in the following years when a trio of illustrators would give TIME’s covers center stage.

Those days would also witness a fundamental change in the maps that illustrated a story. American cartographer Robert M. Chapin Jr. revolutionized journalistic cartography with his innovative technique of adding visual information to the maps. Chapin, as well as Tasker, started working at TIME in 1937. Curiously, cartography wasn’t his original career, he had studied to be an architect. But when he graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 1933, during the worst point of the Depression, most architects were jobless. By chance, Chapin found work retouching photos at Newsweek, and he learned to draw maps during the two years he worked there. By 1937, the rival’s newsmagazine maps had caught the eye of TIME’s Managing Editor Manfred Gottfried, and less than a month later Chapin was installed in the old TIME offices in the Chrysler Building.

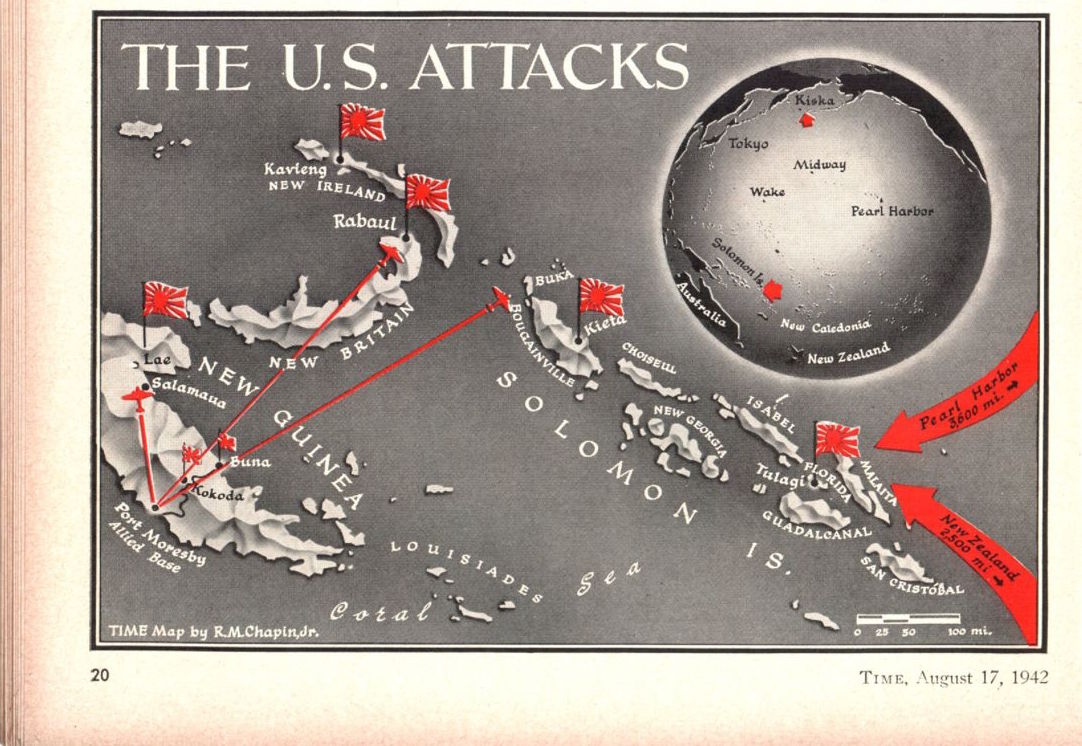

Chapin would remain at TIME for 33 years, during which he turned himself into the first and greatest “infographic” cartographer in the world. His technique revolutionized journalistic cartography with three historical innovations. First, Chapin used an airbrush, a sort of high-power atomizer, with which he sprayed paint over his maps in an infinite number of shadings that gave mountains and valleys, plateaus and riverbeds their three-dimensional height and depth. Second, he suspended two large floating globes — one political, one physical — from the ceiling by pulleys and counterweights in such a way that they could be turned, lowered and photographed from any angle or perspective. Third, he created a library of celluloid symbols, which included bomb explosions, flags, camels, ships, soldiers and moving battalions. “I try to dramatize the news of the week,” [Robert T. Elson’s history of Time Inc.] quotes Chapin as having said, “not just to produce a reference map like those in an atlas.”

Sometimes, he had to be as much a cryptographer as a cartographer. Chapin started drawing between two and three maps a week, but at the beginning of the Second World War, he had to double the amount, compelling him to work overnight to make deadlines, especially with breaking news from the war front. He set up a team to help him. Alone or with their help, Chapin would produce some of the most inventive cartographical “infographies,” such as the Ethiopian invasion by Mussolini’s troops and the Paris liberation. One day in August 1942, a correspondent cabled from Hawaii: “If Chapin is a wise man, he will know what to map in the Pacific.” After some thought, having realized that this was a coded message owing to national security restrictions, Chapin put his finger on a little-known chain of islands named after Solomon in the Bible. The map was drawn and ready to be filled in with last-minute detail, when the navy finally released news of the Guadalcanal invasion four days later.

Chapin’s journalistic cartography became world renowned because of the rigorous geographical details of his maps, and it was (and still is) regularly used as reference material by the American National Library, NASA, the army and the navy, as well as by foreign governments, American and international schools and history book publishers.

Excerpted from the new updated and expanded edition of TIME: The Illustrated History of the World’s Most Influential Magazine (Beaux Arts Editions), available exclusively at Barnes & Noble and BN.com.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com