When new mother Lindsey Hubley returned to the hospital with severe stomach pains a few days after giving birth, she was told it was just constipation and sent home, her lawyer told the Toronto Star this week. Hours later, though, the 33-year-old Canadian was rushed into emergency surgery and eventually diagnosed with necrotizing fasciitis—also known as flesh-eating bacteria.

Hubley was suffering from septic shock, and her organs were shutting down, the Washington Post reports. To save her life, doctors had to amputate below both elbows and both knees, and perform a hysterectomy. Seven months later, she’s still confined to a hospital bed and wheelchair, and last week she filed a negligence lawsuit against the health center where she gave birth.

Necrotizing fasciitis isn’t common. But it does occasionally make the news, usually when a person contracts the illness after exposure to contaminated water—like during Hurricane Harvey—or contaminated seafood. The infection can also strike after childbirth or surgery.

According to Dr. Daniel Caplivski, associate professor in the division of infectious diseases at Ichan School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (who was not involved in Hubley’s care), here’s what you need to know about the rare but deadly infection.

What causes necrotizing fasciitis?

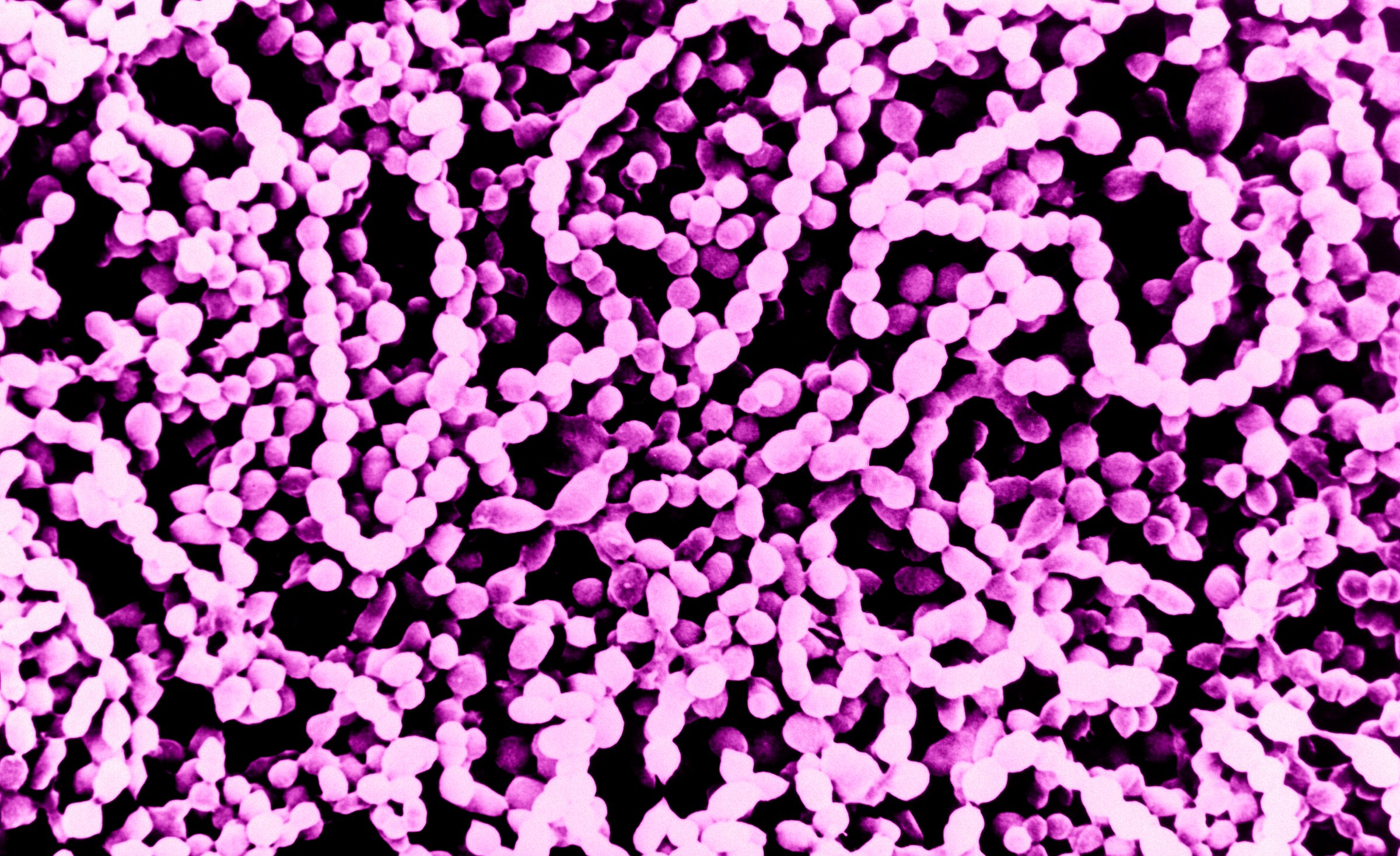

Doctors determined that Hubley was infected with group A streptococcal bacteria, according to the Washington Post, which likely triggered her case of necrotizing fasciitis. Streptococcal bacteria is extremely common; it’s the same bacteria that causes strep throat, but it can also live in people’s throats and on their skin without causing any symptoms at all.

When streptococcal bacteria gets into an open wound, however, it can cause a serious infection. “These bacteria produce toxins, called exotoxins, that cause an overstimulation of the immune system,” says Caplivski. “That can lead to septic shock, which can cause blood pressure to drop very low.” Blood can have trouble reaching hands and feet, and tissue in those areas can die.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), between 700 and 1,100 cases of necrotizing fasciitis occur each year in the United States, and that number does not appear to be rising. Although group A strep bacteria are considered the most common cause, the disease can also be caused by other germs including Clostridium and E. coli.

Cuts, scrapes and surgery can all introduce harmful flesh-eating bacteria

Bacterial infections can happen through a tiny blister, a larger open wound or during a more extensive medical procedure. In Hubley’s case, her lawyers say her placenta was not removed after birth and that there was a tear in her vagina that wasn’t treated with sutures, which they say could have contributed to the infection.

“Childbirth certainly is a time when there is more exposure of a patient’s subcutaneous tissue to the outside world, whether it’s a regular vaginal delivery or a C-section or because women get IVs placed,” says Caplivski. “Those are all potential moments when bacteria could have more access to deeper tissues.”

People with healthy immune systems can usually fight off streptococcus or other invasive bacteria, which is why serious infections are so rare. Most people who get necrotizing fasciitis also have another chronic health problem, like diabetes, kidney disease or cancer. Pregnancy and childbirth may also raise a woman’s risk for infection, says Caplivski, since both can compromise her immunity.

MORE: I Survived Flesh-Eating Bacteria—and It Changed My Life Forever

The initial damage happens below the surface

Despite its nickname, the first sign of necrotizing fasciitis is not usually flesh being eaten away. The infection can cause blisters, ulcers or black spots on the skin, but the tissue just below the skin’s surface is often attacked first.

Because of that, people might experience extreme pain, swelling, fever, chills or other signs of infection before they notice any outward signs. People should pay close attention to symptoms like these if they appear after an injury that breaks the skin, says Caplivski, or after a surgical procedure.

People should also see their doctor if a wound or a surgical site becomes inflamed or feels more painful than they think it should. “In the vast majority of cases, this does not lead to necrotizing fasciitis and can be dealt with with topical or oral antibiotics,” he says. “But when things are not improving and someone is feeling sick despite getting these types of treatment, there could be a more serious infection involved.”

It’s important to get treated ASAP

Symptoms of necrotizing fasciitis can begin as quickly as a few hours after infection. From that point, the infection can spread rapidly and can lead to amputation or death if it’s not diagnosed and treated quickly. “Thankfully, this remains a rare version of group A streptococcus infection,” says Caplivski, “but sometimes the rarity of illness makes it harder to recognize when it does occur.”

Intravenous antibiotics are the first line of treatment against bacteria like group A streptococcus. (Oral drugs aren’t strong enough.) But doctors may also have to remove damaged skin, entire limbs or organs if the bacteria—or a lack of blood flow—has already destroyed surrounding tissues and blood vessels.

Recovery from necrotizing fasciitis can take months

It’s not unusual for someone with necrotizing fasciitis to be in the hospital for months, even after all traces of the infection are gone. “Necrotizing fasciitis often requires multiple surgeries to remove infected tissue,” says Caplivski, “and each surgery entails its own recovery period.”

Patients also have to learn new ways of life—like learning to walk again, adjusting to daily life with amputations and facing an increased risk of complications in the future. “In patients who are unfortunate enough to go through this, the recovery is very prolonged,” he says.

Three months after Hubley was diagnosed, an update on the family’s GoFundMe page noted that the new mom had undergone 14 surgeries along with dialysis and hyperbaric oxygen treatment. “We’re finally confident in saying the recovery phase has started,” they wrote. “We continue to remain positive and thankful for this opportunity to fight for our family.”

Good hygiene and handwashing offer some protection

Though most of it won’t harm you, bacteria is everywhere, and there may be no way to prevent these types of infections entirely. But washing your hands before tending to any open wounds is a good start, says Caplivski. So is making sure your doctors are practicing good hygiene, as well.

“I think hospitals are paying a lot of attention to preventing infections, but it can still be helpful to remind your healthcare workers to wash their hands or use an alcohol-based hand sanitizer before they interact with you or touch your IV,” he says. “And anytime you are worried something isn’t healing the way it should, you want to call attention to it sooner rather than later.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com