These days, the writer John McPhee is synonymous with the captivating and obsessively observed profiles that have made classics of such books as Encounters With the Archdruid and Coming Into the Country. In his latest book, Draft No. 4: On the Writing Process, he turns that famous eye for detail to his own very particular experiences as a writer.

McPhee began his career at TIME in 1957, when individual writers at the magazine were largely subsumed by what was dubbed “group journalism,” a process by which teams of researchers, reporters and stringers all over the world funnelled information to New York to be turned into articles by the writers and editors in the office. The finished product would not identify the writer by name. Everything was simply a product of TIME.

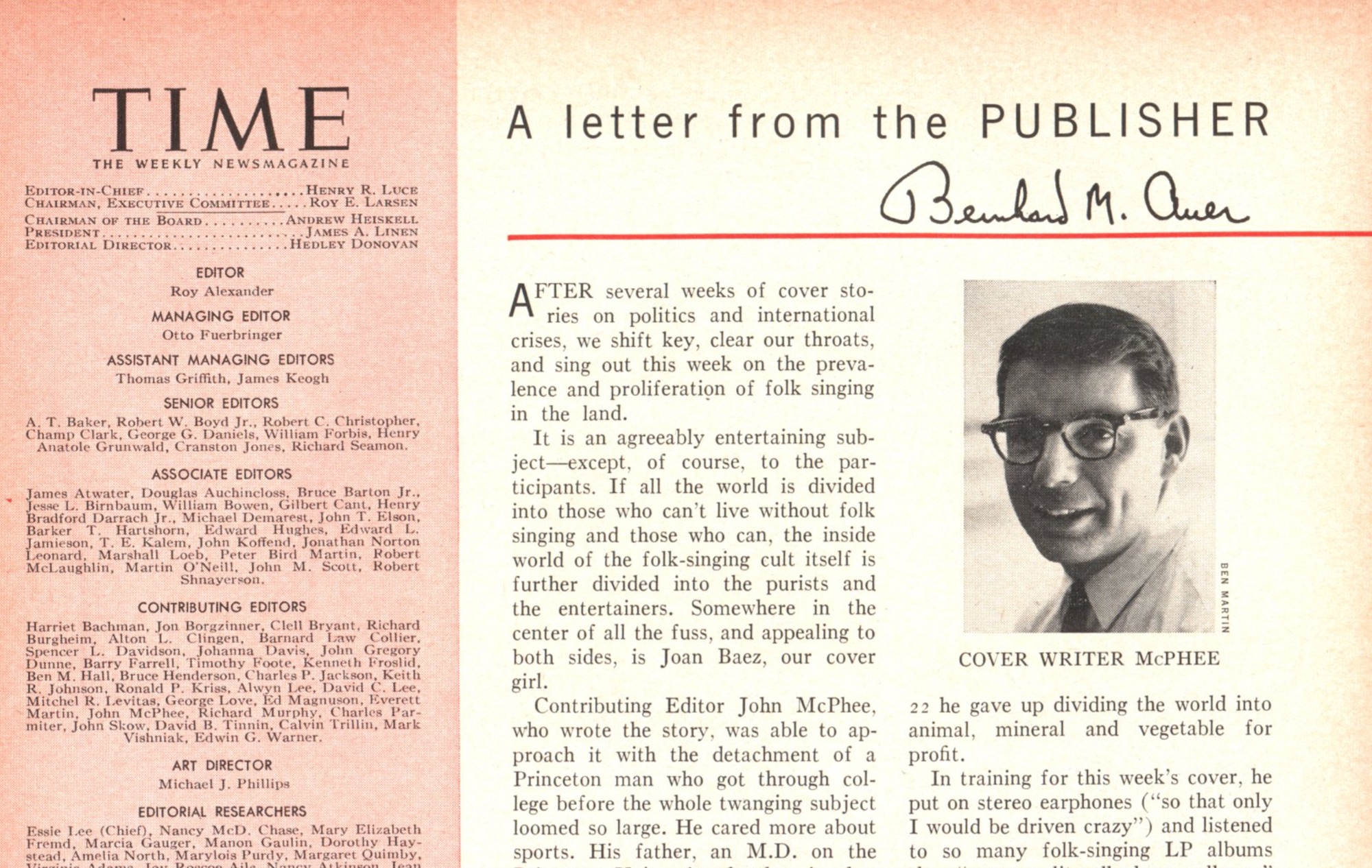

And yet there were exceptions — one of which merited a mention in the weekly letter from the publisher to readers.

In 1963, when the actor Richard Burton was the subject of a cover profile, he only consented to be interviewed on the condition that McPhee, whom he’d met in the process of the research for an earlier story, do the whole thing from start to finish. Burton’s request worked so well that the writer Dwight Macdonald, then of The New Yorker, the magazine to which McPhee would soon move, wrote to congratulate the magazine and writer after the profile ran. “Without either apologizing or moralizing, Mr. McPhee conveyed the pathos (tragedy would be too big a word) and the self-destructiveness (selling-out would be too small a word) of Richard Burton‘s career,” Macdonald wrote. “I note that Mr. Burton agreed to the story ‘on the condition that McPhee do all the interviewing of him as well as the writing.’ Perhaps the peculiar excellence of this article may be due to nothing more complicated than its being the product of one writer as against that of a committee of editors.”

McPhee spoke to TIME about Draft No. 4 and how things have changed since his days at TIME.

TIME: You write that you’d rather be watching people than interviewing them, but unfortunately we’re talking on the phone. Is there anything I would see if I were there in person that I should know about?

JOHN MCPHEE: No, I’m sitting in the place where my computer is, at home, with a bunch of photographs around me and a ton of unanswered emails.

You’ve been teaching writing at Princeton for more than four decades. Do you think you can see your work as a teacher coming through on the page in your work as a writer?

Not so much on the page but I think it has had a very large effect that I can’t really measure. I think that the teaching has increased my productivity, or whatever you want to call it, rather than diminished it. For most years I’ve taught two spring semesters in a row and then not the third. That’s hardly a huge dent in your time, but I’ve never written anything during the semester when I’m teaching. And then I go back to it and I think I’m refreshed and more eager to do it.

This book is all about your particular personal experience as a writer, but you spent years at TIME in the era of “group journalism.” What did you think of that process?

I looked upon it as, you know, ‘What do I know?’ In some ways it had to exist. You’re collecting material from all over the world, somebody in New York does the writing and these other people are filing things, and it’s a group effort, that made sense to me. There were no bylines at all. Those publisher’s letters were something like a super byline — in other words, no byline, however there’s a whole page up in the front. That was kind of an irony. However, that was just the custom then, as it was the custom that males were writers and women were researchers. That began to disappear in my time there but when I first got there that was the set-up. In retrospect, I see it a lot differently from when I first got there and I was naïve and starting out.

Did you think of the pieces you produced during that time as “your” stories?

Absolutely. Most of the writers in the back of the book were, I think, like me in this respect. Show Business [the section for which McPhee worked] would be different from what was then called Foreign News and National Affairs, and by necessity those were more group efforts. So I was sort of lucky. I got to do more of reporting and writing back there, and I think also fewer people were fussing over it than were fussing over political news.

Can you take me through the process of writing a story in those days?

You went to story conference at the beginning of the five-day week. On the first day we had a story conference and bureaus around the world had sent in ideas, the writer had ideas to suggest, the senior editor had ideas to suggest. You sat around this room and then the stories were chosen. There were times when there were a couple of writers in Show Business but mostly it was just a one-person section for me. The story conference would settle what the stories were. I was pretty passive about that, I didn’t come with a whole bunch of ideas. I had something usually but I was on the receiving end of ideas coming from wherever. That was day number one.

I think it was the fourth night, when we were finally writing. Week after week after week I was there until it was light outside the window, just because of my own nature as a writer. I couldn’t even get started. Gradually, the pressure of the week would cause you to, but I was up all night one night a week, and that wasn’t anybody’s fault but my own. I had the material there. And also, I wasn’t alone in this habit.

So anyway, then production would give you items to “green” [cutting words to fit print space]. You’d been at it all week — I describe this in the book, about greening — but that happened every week. You’d come in after you’d been up all night with one thing or another and your piece had been initialed by not only your senior editor but the managing editor, and then there’s somebody telling you to take seven lines out of it. That turned into a writing exercise in my writing class at Princeton; I give it to them every year.

Do you have any favorite memories about the culture of the place in those days?

First of all, you had to be there. Because of the greening, you had to stay to the real end of the week, even after your pieces had been processed in all kinds of ways with a senior editor and all that, you still had to be there. So everybody was there.

Caterers came in, in white coats and a chef’s hat sticking up like a mushroom, and they served stupendous food. But you took it on your tray back to your desk and you ate it there. And of course there was a flowing bar with it all, and it was a very collegial time. Jerry Goodman and I would sit at my desk, routinely; Jerry Goodman was George J.W. Goodman, who later wrote books under the name of Adam Smith. I don’t know how I got to know him but he would come with his filet mignon on a tray.

In the course of the years, in a general way, the digital age has separated people. Of course it brings you all together in different social media but, for example, for some years now I haven’t needed to be in New York when a piece was published. A lot of the collegiality, the friendship, doesn’t happen anymore because electronics are so brilliant.

So much of your more recent work is far from the show-biz coverage you worked on at TIME, and a lot of it is very close to the Earth in one way or another. Do you consider yourself an environmentalist? Do you consider your work political?

I’m looking for people to write about and I’m drawn to people in places that are, I don’t know, in my own background. I spent my youth and my summers on canoe trips and all that kind of thing. But with a primary agenda in order to defend the environment? If it happens incidentally, it happens incidentally, but it’s not a primary thing with me at all. I don’t set out to be an environmentalist writer at all. But environmentalists interest me, because of the environment they are defending. I hope you can see what I mean.

That the people come first.

Yes. What my work has in common is that all of it is about real people in real places. I am always looking for stories to tell, for people to interview. And so it’s very miscellaneous, this work, in terms of themes and backgrounds and subjects, but all of it is about real people and real places, and that’s what my work is about and that’s what it has in common.

What do you read for pleasure?

Right now I’m reading The Honourable Schoolboy. I listen to a lot of books on tape in my car. Even driving from my house to the university, which is four miles, I have [John] le Carré or someone reading when I turn on the ignition, just picking it up from wherever it was. John le Carré — David Cornwell — is a stupendous reader. You’d think he was trained in a rep company. His books are recorded by all kinds of people, including him, but go for the ones where he reads.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com