The declining value of the truth may seem to define a particularly modern phenomenon. This week saw U.S. President Donald Trump continue his Twitter accusations against so-called “fake news”—after a year in which Oxford Dictionaries made post-truth the word of the year for 2016. This trend reflects an apparent shift into an age where politicians and campaigners jettisoned their traditional desire to avoid being caught telling blatant, demonstrable lies.

Yet of course, as the ancients knew, there is no new thing under the sun.

If there were ever such a thing as a post-truth era, it began precisely 710 years ago, at dawn on Friday, Oct. 13, 1307, in the kingdom of France. On that day, government agents swooped in on every property belonging to the world-famous Knights Templar, arrested their members on false charges and began a process of interrogation, public examination and reputational demolition that ended four and a half years later with the order being dissolved. Though the events of that day are not the source of superstition about Friday the 13th—contrary to rumor—they do hold lessons for today.

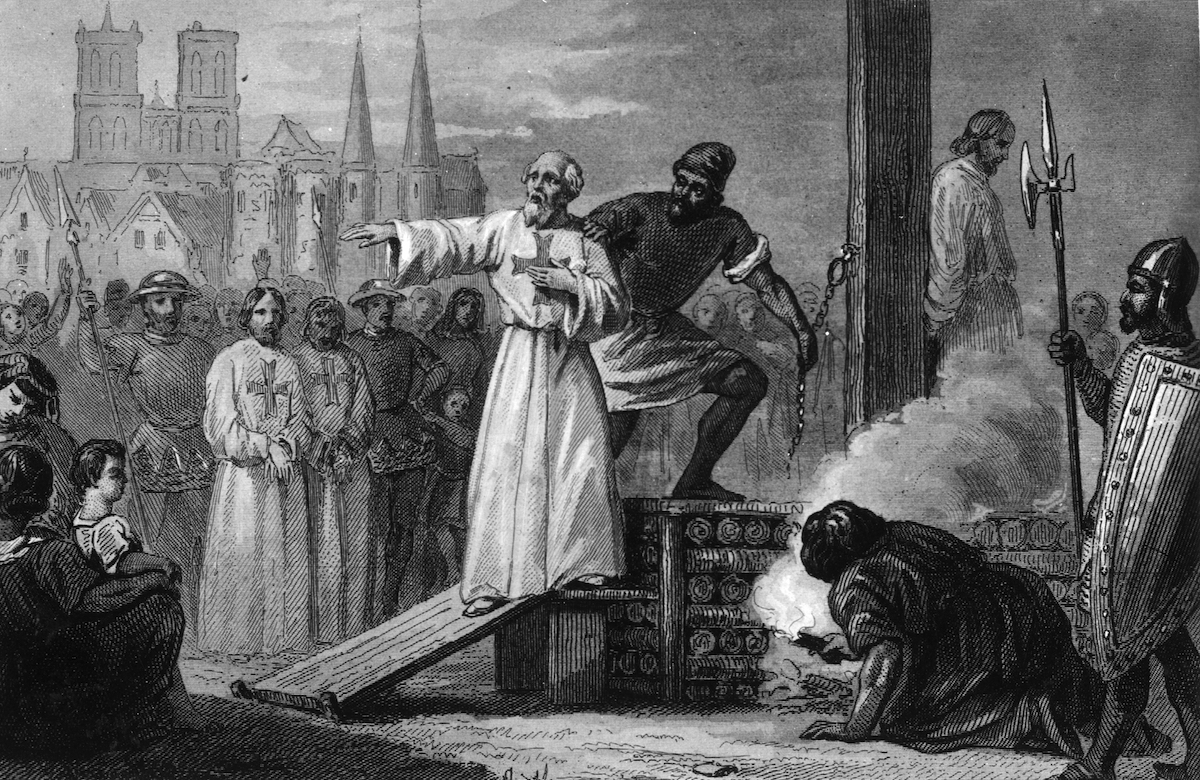

The Templars were a medieval military order, set up during the crusading period, named for their initial headquarters on the Temple Mount (Haram al-Sharif) in Jerusalem. They recruited western, Christian warriors who took an oath to live quasi-monastic lives devoted to the principles of chastity, poverty and obedience, and wore iconic uniforms of black or white robes emblazoned with a red cross.

Initially these men were tasked with defending pilgrims around Christian-occupied Jerusalem, but over time they expanded their role. During the 12th and 13th centuries the Templars developed an elite military wing devoted to ferocious warfare against the Islamic rulers of Syria, North Africa and the Iberian peninsula, supported by a vast, profitable business empire of land and property on which they paid very little or no tax.

By 1307, however, the crusades were going badly. Calls for reform of the Templars were becoming commonplace. The order’s popularity was waning. And they had acquired a calculating political enemy in the form of King Philip IV of France, who wished to roll up the Templars and appropriate their wealth as a means of balancing a troublesome budget deficit.

The methods used to bring down the Templars were chillingly efficient and post-truthy as hell. Prior to the Friday 13th arrests, the king’s ministers had spent more than a year interviewing disgruntled former Templars and compiling a small, questionable, sexed-up dossier of supposed misdeeds, including allegations that Templars had spat on the cross, denied Christ, kissed one another in homoerotic induction rituals and worshiped false idols.

These charges were written up in formal letters of condemnation expressed through hyperbole that would be in no way out of place in the average Twitterstorm today. The Templars were condemned en masse as having disgraced the French flag and the country. Their crimes, wrote the king, were “horrible to contemplate, terrible to hear of.” His accusations were widely circulated, and his campaign to destroy the Templars rested on the relentless, repetitive dissemination of his baseless claims in every public arena he could find.

Over several years, this medieval “fake news” was repeated over and over again, its loudness and frequency making up for the fact that it was a lie, until in 1312 a council of the Church reached the conclusion that the Templars’ name had been so blackened the order’s members ought to be forcibly retired.

The first reason given by the papal order dissolving the Templars was the very fact of “infamy, suspicion, noisy insinuation.” The knights were thus blown away by a gust of hot air—confessions obtained by torture were used to back a relentless campaign of simple, repetitious falsehood.

Truth? What truth?

The story of the Knights Templar is often dusted off for the purposes of popular entertainment and conspiracy-mongering. On the one hand are The Da Vinci Code and the video-game franchise Assassin’s Creed, in which the Templars are time-hopping agents of a deathless global plot to subvert or rule the world. On the other we have frequent, endless speculation about so-called Templar treasure, rumored to be buried on Oak Island, Nova Scotia, or in some remote Scottish location.

All this is good fun, but it misses the point of the Templars’ story, which has many instructive echoes today.

As crusaders, the order’s members were involved in a three-way struggle in Syria, Palestine and North Africa, fought between factions of Sunni and Shia Islam, and western, Christian military occupiers who became enmired in a war from which they could not escape but which they could not “win.” This war was long, expensive and in the end unpopular, and its effects were felt not only on the battlefields of the near and middle east, but in the west, too.

One of the enduring stories of this Middle Eastern misadventure was the phenomenon of religiously jazzed young men making their way to Syria to throw themselves into war. We need not search very hard for examples of exactly that phenomenon right now.

Meanwhile, the Templars as an organization represented a disruptive idea (in this case the monk-knight hybrid) that began as a small start-up, branded itself brilliantly, quickly raised funds and a public profile, gained a foothold in countries all over the world, negotiated highly favorable tax deals with their governments, became dazzlingly wealthy and highly financially inventive and frequently caused those same governments problems, owing to their global reach and relative freedom from oversight.

And of course, as we have seen, the downfall of the Templars shows us that fake news was most definitely not invented by the President of the United States in 2016, but was a tool at the disposal of a king of France more than seven centuries before him.

Plus, there’s a postscript, which comes by way of an irony. Earlier this year Joshua Green’s excellent book Devil’s Bargain: Steve Bannon, Donald Trump and the Storming of the Presidency outlined how the former White House strategist absorbed as a younger man the writings of the French traditionalist René Guénon.

“Guénon, like Bannon,” writes Green, “was drawn to a sweeping, apocalyptic view of history that identified two events as marking the beginning of the spiritual decline of the West.”

One was the Peace of Westphalia of 1648. The other was the destruction of the order of the Temple in 1312.

Dan Jones is the author of The Templars: The Rise and Spectacular Fall of God’s Holy Warriors, available now from Viking.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com