This post is in partnership with the History News Network, the website that puts the news into historical perspective. The article below was originally published at HNN.

Eleanor Roosevelt had more than one professional life. Enmeshed with her accomplishment in politics and diplomacy was a complementary career as journalist, lecturer, broadcaster and public personality. ER wrote incessantly. Her body of writing—and speaking—was prodigious. She reached a mass audience through magazine articles, newspaper columns and radio talks. From the 1920s into the 1960s, ER both generated news and wrote about it. Ambitious and competitive, she dealt continually with deadlines and agents, publishers and editors, radio stations and corporate sponsors. The upshot: much that ER achieved in public affairs had double resonance, in life and in print. Her huge written legacy, so astutely mined by biographers, speaks to the present moment.

ER wrote and spoke about subjects of enduring interest—about women’s role in society and politics; about education, race, labor rights, civil rights, human rights, and world peace; and about human emotions and interpersonal relations. Almost every topic she touched, even if somewhat “dated,” as is often the case, connects in some way with modern readers—from her advice on marriage to her assault on Soviet intransigence at the UN—to say nothing of her many responses to the question “Can a Woman Become President?” (As of 1940, “No.”) Dismissing “the America First people,” she pressed for international understanding. Taking aim at bias and bigots, she endorsed “the four equalities”: voting rights, equal education, equal opportunity and justice before the law.

What motifs pervade ER’s vast outpouring? One is personal narrative. In no small part, ER wrote about herself. Beyond three impressive memoirs, plus a fourth that melds the first three, ER infused her other writings with facets of her life story. Early memories and childhood experiences flood her columns and articles. She often mentioned her notable family, her adored father and her famous uncle, Theodore Roosevelt. She recalled her beloved teacher, Marie Souvestre; her domineering mother-in-law; and the impact of the Roosevelts’ talented political advisor, Louis M. Howe. She reflected on her relationship with FDR and after his death rewove it by speaking for FDR. At once candid and evasive, self-effacing and dramatic, ER found many ways to share her backstory, or legend.

Another motif was educational process. Always a teacher and always a gifted student, ER underscored the imperative of learning from experience. The main axiom of progressive education—to learn by doing—was central to her credo. So was educational philosopher John Dewey’s basic tenet (unacknowledged) that learning meant a continual process of restructuring and reorganizing, or in ER’s rendition, “readjustment.” To ER, as to Dewey, the gist of education involved learning how to learn. Touting the value of curiosity and looking back on her own example, ER stressed the importance of learning from experience and of readjustment; she merged learning theory with popular advice.

Finally, and most extensively, ER expounded on democratic values. Her arguments drew on her commitment to labor rights, civil rights and human rights; on her beliefs about the interdependence of people and nations; and on her enmity to totalitarianism. She spoke at once to her contemporaries and to posterity. To listen to ER defend democratic values right now—at a time when the executive branch is anti-labor, anti-regulatory, anti-internationalist, and overwhelmingly anti-New Deal—induces shock.

“We must learn to work together, all of us, regardless of race or creed or color; we must wipe out, wherever we find it, any feeling that grows up, of intolerance, or belief that one group can go ahead alone,” ER told a conference of educators in 1934. “We go ahead together or we go down together.” To ER, democracy involved interdependence. It rested not just on economic security or on equal opportunity, but on a cooperative community and a sense of responsibility for one another. “We are all so separated from each other, that we forget our interdependence,” ER wrote in 1931. Through the Depression years, as after, ER saw society as an organic whole. Her “theory of a democratic way of life” connoted connectedness and mutuality. “Our own success, to be real, must contribute to the success of others,” she wrote in 1940. “That means an obligation to the coal-miners and sharecroppers, the migratory workers, the tenement house dwellers and farmers who cannot make a living.”

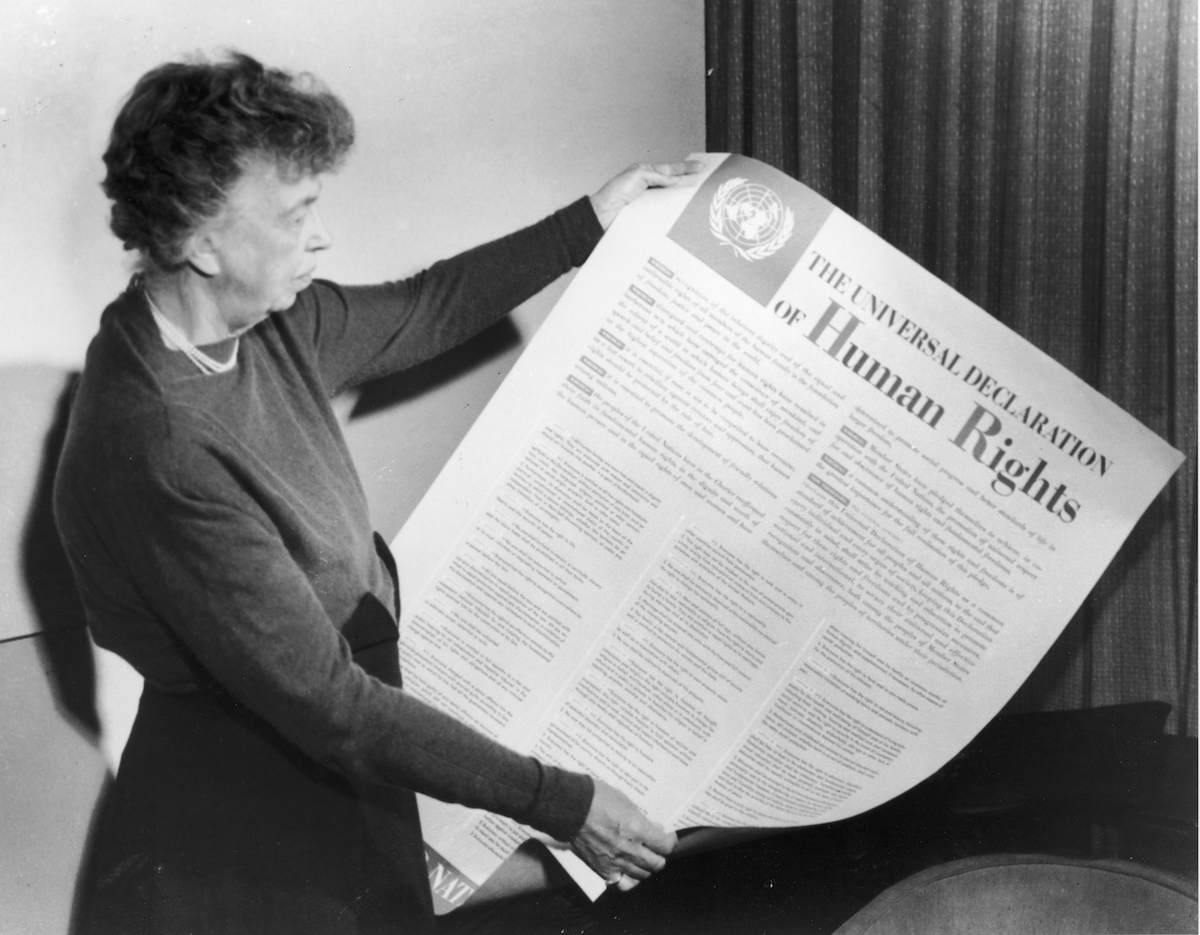

As World War II began in Europe, ER’s promotion of democratic values surged. To fight fascism abroad demanded more democracy at home; inequality and bigotry were wartime liabilities. Any type of prejudice, in race or religion, endangered not just specific targets but everyone, she wrote in 1939; “the real wrong is done to democracy and our nation as a whole.” On visiting an Arizona internment camp in 1943, ER drafted an article that voiced her disquiet. To fear other Americans, ER wrote, challenged every citizen’s “right to our basic freedoms” and undercut US capacity to “furnish a pattern for the rest of the world.” In the postwar years, when she led the U.N. commission that drafted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, her vision of interdependence took global form. Advance of human rights rested on a shared respect for the rights of others, a cooperative community, and a sense of mutual obligation. “We will all have more security if we have a greater sense of interdependence,” ER wrote in 1947, “and count less on our own individual strengths.”

ER never saw democratic values as safe from threat. Economic insecurity, fear of difference, a spirit of greed—all imperiled democracy. Looking at the immediate postwar world (biographer Blanche Wiesen Cook cites this passage in her third volume), ER saw that totalitarianism could arise at home as well as abroad. “There is nothing, given certain kinds of leadership, which could prevent our falling a prey to this same kind of insanity,” ER wrote in May 1945. If “equal opportunity, equal justice, and equal treatment” did not reach all U.S. citizens, she posited, “the very basis on which this country can hope to survive with liberty and justice for all will be wiped away.”

Nancy Woloch is a member of the history department at Barnard College, Columbia University. Her latest book is Eleanor Roosevelt: In Her Words: On Women, Politics, Leadership, and Lessons from Life.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com