With more than 200 NFL players choosing to sit or kneel while the national anthem played before football games over this past weekend — largely in response to President Trump’s continued criticism of athletes participating in such demonstrations — it’s worth remembering that this movement didn’t just begin last year with former 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick’s decision to kneel in order to make a statement about how the country is not practicing what it preaches.

In fact, this week’s protests are simply the latest in a long history of athletes making public statements in the name of civil rights and American patriotism. Here are the answers to some key questions about the moments that led up to the NFL players’ latest act of resistance:

Why is “The Star-Spangled Banner” part of sporting events?

The patriotic song became a fixture at sporting events during the last century. During the seventh-inning stretch of Game 1 between the Red Sox and the Cubs on Sept. 5, 1918, a Red Sox third baseman and furloughed U.S. Navy sailor sang “The Star-Spangled Banner” — then just a military anthem, not the official national anthem — as a band played in the outfield. His rendition was particularly moving because it took place as American soldiers were fighting abroad in World War I. The crowd’s positive response was a major reason why the song was incorporated into sporting events throughout the nation. It became a permanent fixture of football games in the wake of World War II.

Is the anthem itself controversial?

Some supporters believe that the history behind the anthem itself makes its performance a fitting time for African-American athletes to protest, given the politics of its writer, Francis Scott Key. “He supported sending free blacks (not slaves) back to Africa and, with a few exceptions, was about as pro-slavery, anti-black and anti-abolitionist as you could get at the time,” Jason Johnson, a political scientist at Morgan State University, writes for The Root. In addition, a third stanza that is almost never sung is specifically disparaging toward the runaway slaves who joined the British Army during the War of 1812 in exchange for their freedom.

Are the players the first to use kneeling as a protest?

Kneeling has long been an act of prayer and political activism. Take, for example, a photo from 1965 that’s gone viral in the last 24 hours, featuring the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. and other civil rights activists kneeling in prayer Selma, Ala., after more than 250 protesters were arrested on a march to the Dallas County Alabama courthouse to help get fellow African-Americans registered to vote.

Have football players protested before?

Yes. For example, a week before the American Football League’s all-star game was set to kick-off in New Orleans, 21 African-American professional players refused to play in the Big Easy because of discrimination that made it impossible for them to enjoy themselves in the week leading up to the game. One of the leaders of the walkout, former Oakland Raiders running back Clem Daniels, recently recalled to TIME the prejudice he and fellow faced trying to do everything from hail a cab to hanging up a coat.

What’s the history behind Seahawks player Michael Bennett raising a fist on the field?

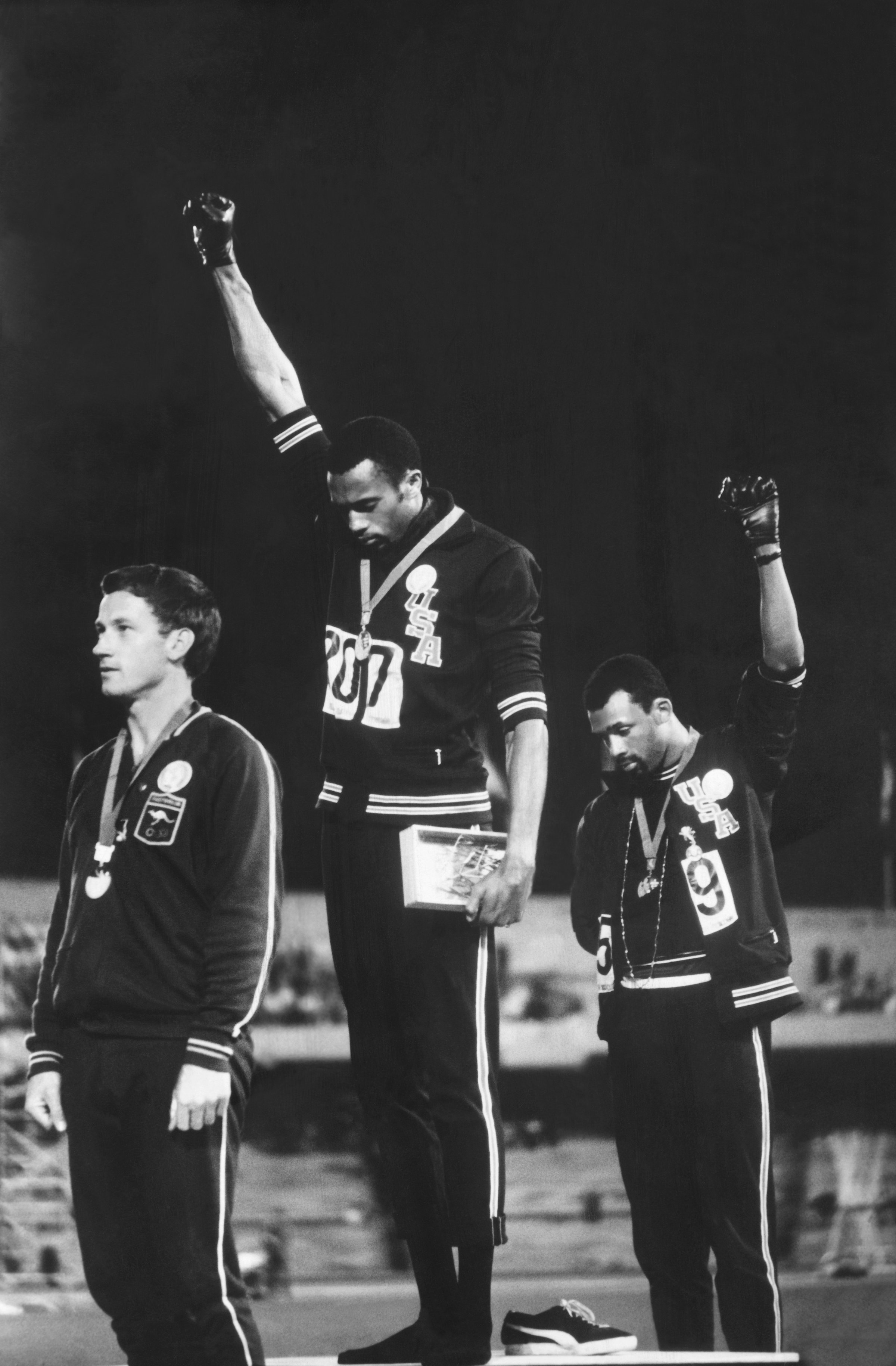

The raised fist of the “Black Power” salute is perhaps most famously associated, at least within athletics, with its use during the 1968 Olympics. LIFE.com has shared the story of the iconic photo of the moment during the medal ceremony for the men’s 200-meter event at the Summer Games in Mexico City, when gold medalist Tommie Smith and bronze medalist John Carlos raised glove-covered fists. Silver medalist Peter Norman supported them by wearing a badge representing the Olympic Project for Human Rights. “We were just human beings who saw a need to bring attention to the inequality in our country,” Smith said years later, in a 1999 documentary on the moment Fists of Freedom.

What about other sports?

There are many athletes outside of football who helped pave the way for the national anthem protests of 2017, and at least one famous story shows how standing up a cause can have ramifications long after the game ends. The late boxer Muhammad Ali, a devout Muslim, is not only known for being the first three-time heavyweight world champion, but also for refusing to enlisting in the Vietnam draft three times, arguing that “war is against the teachings of the Koran.” TIME’s Oct. 3, 2016, cover story on today’s football protests characterized Ali as a cautionary tale, whose draft evasion conviction in 1967 showed that there can be “consequences for sticking one’s neck out.” For Ali, that consequence was being stripped of his boxing license and titles, including the heavyweight crown he won by beating Sonny Liston in 1964. (A TIME obituary Ali elaborates on his fight to be recognized as a conscientious objector, while this LIFE.com photo gallery documents his life in exile.) Ali’s conviction was eventually reversed by the Supreme Court but the episode remained an example of the high stakes of protest — and today, three weeks into the NFL season, Kaepernick remains unsigned.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com