A.A. Milne’s charming tales of honey-loving Winnie-the-Pooh, timid Piglet, grumpy Eeyore and their human friend Christopher Robin have delighted readers for generations. But many are likely unaware of the darkness underneath the book’s surface.

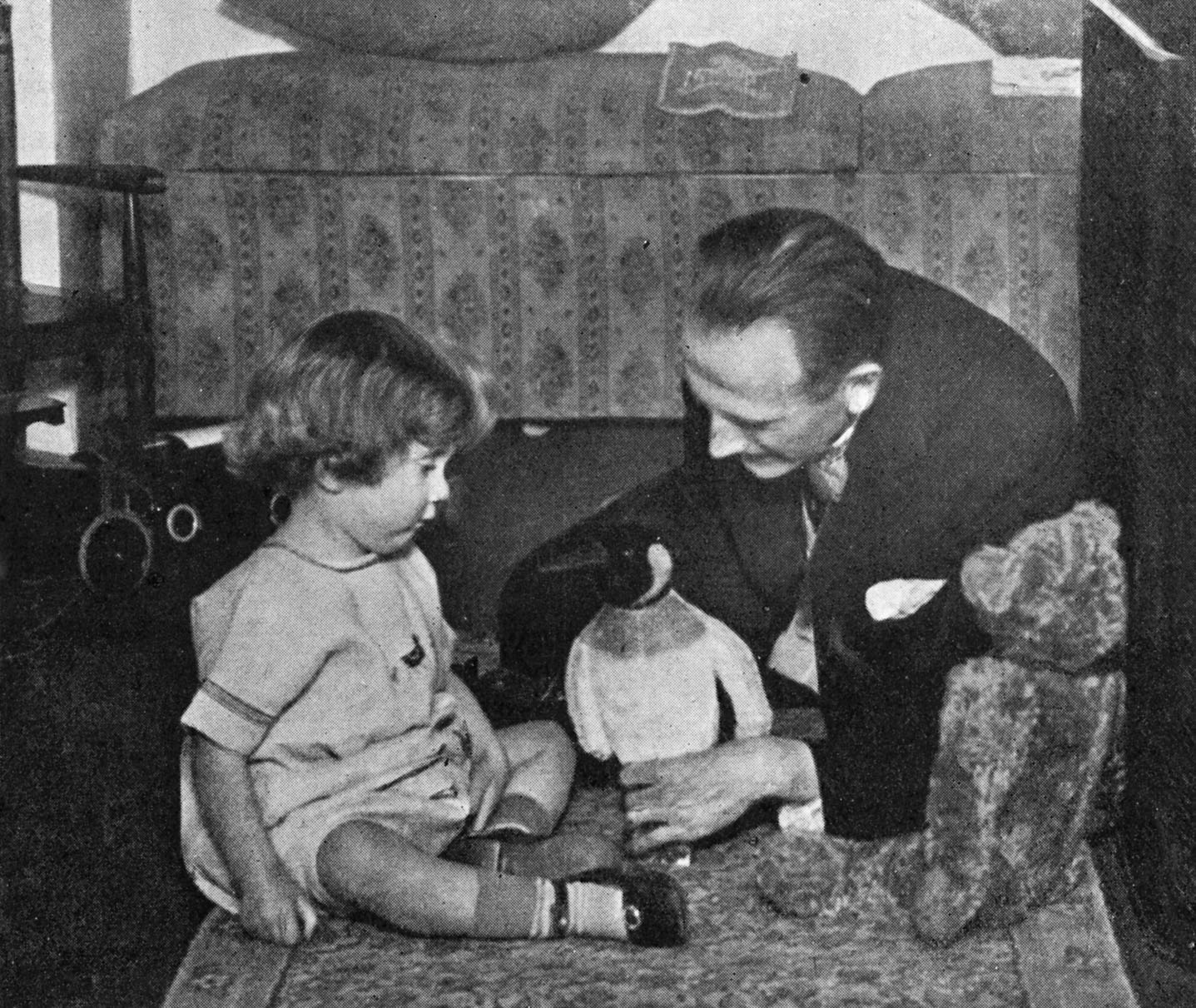

The real story behind the Winnie-the-Pooh series is the subject at the heart of a new movie called Goodbye Christopher Robin, starring Domhnall Gleeson (Brooklyn) as Milne and Margot Robbie (Wolf of Wall Street) as his wife Daphne. The film suggests that, among other things, Milne’s relationship with his son, the real-life Christopher, was difficult. But how true is the movie, which hits theaters Oct. 13, to reality?

A.A. Milne suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder

In Robin we see how Milne’s post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), the result of his fighting for the British Army in World War One, led him to move his family away from London to the peaceful English countryside.

Although there is no direct evidence that Milne suffered from what we commonly know now as PTSD, his experiences during the war weighed heavily on him. In his autobiography It’s Too Late Now, Milne wrote that it made him “almost physically sick” to think of “that nightmare of mental and moral degradation, the war.”

He referred to a trip to the Insect House at the Zoo with Christopher Robin, where the sight of the “monstrous inmates” triggered intense discomfort. “I could imagine a spider or a millipede so horrible that in its presence I should die of disgust,” he wrote. “It seems impossible to me now that any sensitive man could live through another war. If not required to die on other ways, he would waste away of soul-sickness.”

Daphne sold Milne’s ‘Vespers’ poem without him knowing

Milne wrote ‘Vespers’, possibly his most famous poem, in 1923. The sentimental poem ends with the lines: “Hush! Hush! Whisper who dares! Christopher Robin is saying his prayers.”

In Robin, Daphne has her husband’s poem published in Vanity Fair without his permission or knowledge. In reality, the poem was published in Vanity Fair, however some reports suggest that Milne had told his wife she could keep the money if she managed to sell the poem to a magazine.

‘Vespers’ was “disown[ed]” by Christopher Robin in his autobiography, The Enchanted Place, first published in 1974. “[It is] the one [work] that has brought me over the years more toe-curling, fist-clenching, lip-biting embarrassment than any other,” he wrote.

Daphne was a devoted but absent mother

Robin suggests that Daphne Milne was more concerned with her socialite duties than caring for her son — whom she left almost solely in the company of his nanny, Olive, known affectionately by Christopher Robin as ‘Nou’.

However, that was not necessarily the full story. “When a child is small it is his mother who is mainly responsible for the way he is brought up. So it was with me. I belonged in those days to my mother rather than my father,” Christopher Robin writes in The Enchanted Place.

In real life, Daphne might deserve more credit than she is given in the movie for helping to bring the world of Pooh to life. “It was my mother who used to come and play in the nursery with me and tell him about the things I thought and did. It was she who provided most of the material for my father’s books,” Christopher Robin once said, according to the New York Times.

That said, Christopher Robin’s relationship with his mother was, by all accounts, not a functional one. After his father died in 1956, Christopher saw his mother just once in the remaining 15 years of her life, according to the Oxford Biography Index and Country Living magazine.

The real Christopher Robin told a journalist in the 1970s that he wasn’t angry with his parents and had said goodbye to them “long ago.”

Christopher Robin hated the fame the books brought him

Robin, who died on April 20, 1996, at the age of 75, did not always hate being associated with the Winnie-the-Pooh stories. Initially, as a young boy, he enjoyed the novelty of being famous. “It was exciting and made me feel grand and important,” he told the same journalist in the 1970s.

However, as the movie only very lightly touches upon, things changed when he turned around eight or nine and was sent away to boarding school, where he was relentlessly bullied.

“For it was [then] that began that love-hate relationship with my fictional namesake that has continued to this day,” he wrote in The Enchanted Place. “At home I still liked [Christopher Robin], indeed felt at times quite proud that I shared his name and was able to bask in some of his glory. At school, however, I began to dislike him and I found myself disliking him more and more the older I got. Was my father aware of this? I don’t know.”

Certainly, Milne didn’t seem aware of the negative impact his books had on his son. “The publicity that came to be attached to ‘Christopher Robin’ never seemed to affect us personally, but to concern either a character in a book or a horse that we hoped at one time would win the Derby,” Milne wrote in his 1939 autobiography.

Later in his life, Christopher Robin seemed able to reflect on what had frustrated him about the books. “When I was three my father was three. When I was six he was six… he needed me to escape from being fifty,” he wrote at the end of The Enchanted Place.

Milne was passionately anti-War

The film suggests that Milne was vehemently against war and hoped to write in condemnation of it — until Pooh got in the way. This is true; Milne’s Peace With Honour, a earnest plea for pacifism, was published in 1934. However, much to his frustration, he remained best known for his books about a honey-loving bear.

“[I am writing this book] because I want everybody to think (as I do) that war is poison, and not (as so many think) an over-strong, extremely unpleasant medicine,” he wrote in Peace With Honour. “The last war involved women and children and the accumulated wealth of civilisation in slaughter and ruin. The next war will involve them in a much greater slaughter and ruin. This seems to be a good reason for making the next war impossible.”

However, despite his pacifist credentials, Milne voluntarily enlisted in the British Army during the First World War — although he is famously noted to have said that he never fired a shot at the enemy.

A letter written by Milne which is on display at Imperial War Museum in London encapsulates the moral dilemma he faced as a pacifist in the build-up to the Second World War. “I believe that war is a lesser evil than Hitlerism, I believe that Hitlerism must be killed before war can be killed,” he wrote.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- L.A. Fires Show Reality of 1.5°C of Warming

- How Canada Fell Out of Love With Trudeau

- Trump Is Treating the Globe Like a Monopoly Board

- Bad Bunny On Heartbreak and New Album

- 10 Boundaries Therapists Want You to Set in the New Year

- The Motivational Trick That Makes You Exercise Harder

- Nicole Kidman Is a Pure Pleasure to Watch in Babygirl

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Write to Kate Samuelson at kate.samuelson@time.com