Politicians and pundits often cite the Founding Fathers to prove that their views on the role of government are in line with the original vision for American democracy. But misquoting them has also become something of a tradition in itself.

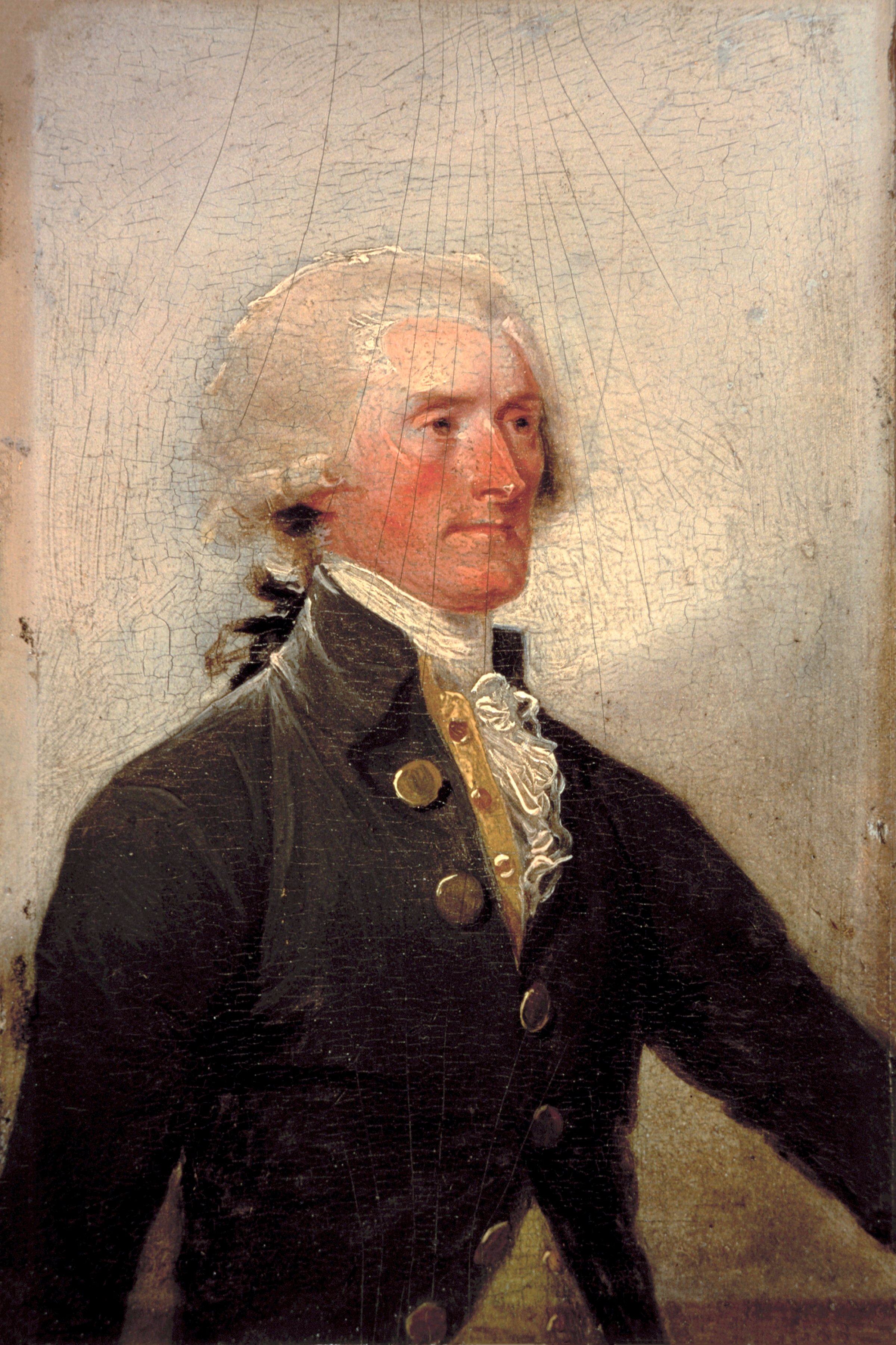

The latest such gaffe happened on Fox & Friends on Thursday. In the course of a discussion about Sens. Lindsey Graham and Bill Cassidy’s bill to revamp the Obama-era Affordable Care Act, Vice President Mike Pence backed up his argument with these words: “Thomas Jefferson said, ‘Government that governs least governs best.’”

Except Thomas Jefferson didn’t actually say that.

Pence is not the first to make the mistake. The late columnist William F. Buckley, Jr. and Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker have done so too, and, in fact, people have been misattributing those words to Jefferson for at least a century and a half, since Edward Peterson’s History of Rhode Island did so in 1853. The quote is commonly associated with the small federal government ideology espoused by Jefferson’s political party, the Democratic-Republicans. But, while the phrase has been found in Henry David Thoreau’s 1849 essay “Civil Disobedience,” law professor Eugene Volokh says that Thoreau was not quoting Jefferson. Instead, he was quoting a man named John O’Sullivan — also the coiner of the term “Manifest Destiny” — who used it in the first 1837 issue of United States Magazine and Democratic Review.

Indeed, The Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia has a whole feature devoted to debunking the history of that specific quote — and other “spurious” Jefferson quotations. And it’s not just Jefferson: Mount Vernon’s site boasts a similar website for George Washington. You can keep these elements in mind — from experts on Thomas Jefferson, Ben Franklin, and George Washington — when you come across a quotation that seems too good to be true:

Grammar and Spelling

Quotes attributed to Jefferson that use contractions and “you” as an indefinite pronoun are usually fishy to Anna Berkes, research librarian at the Jefferson Library at Monticello. One of Berkes’ favorites in this category is, “When you reach the end of your rope, tie a knot in it and hang on.”

Spelling can also be a give-away, as some of the Founding Fathers had unique ways of spelling words. For instance, Jefferson usually spelled “knowledge” as “knolege,” and “yield” as “yeild.” Even so, when Berkes sees Jefferson associated with the quote “I have nothing but contempt for anyone who can spell a word only one way,” she can tell it’s fake because he is “pretty consistent in his spelling, so for him to say this would be very strange.”

However, these clues can be hard to spot. Over the centuries, well-intentioned transcribers have corrected the spelling or sentence structure for modern-day readers, eliminating the hints. For instance, “Jefferson never capitalized the first letter of a sentence, but people have corrected that,” Berkes says.

Anachronisms

If you want to spot a false quotation, it helps to know a little bit about the times in which these men lived. One quote often attributed to Jefferson about private banks uses words that hadn’t entered the lexicon during his lifetime, like “inflation” and “deflation,” Berkes says.

And it’s not just a matter of word choice. Knowing about the times in which these men lived helps find attributions that don’t make sense. For example, Jefferson was a Virginia planter from a privileged background, so modern audiences should beware of any quotes associated with him in which he appears to suggest that he’s pulled himself up by his bootstraps.

Profanities

When it comes to the first President, watch out for quotations that are a little too colloquial. “An army of jackasses led by a lion is stronger than an army of lions led by a jackass” is a quote that often gets misattributed to George Washington.

“If you see something profane or flippant, it’s highly unlikely he said it,” says William Ferraro, Managing Editor and acting Editor-in-Chief of The Papers of George Washington at the University of Virginia. “He was very conscious about the fact that he wasn’t college-educated or formally or classically trained, so he took great pains through his reading and own writing to be careful with diction and sentence structure and use very sophisticated language.”

Gossip

“If you see a quote where Washington is blowing his own horn, it’s probably a fake quote,” Ferraro adds, “If you see some kind of quote that seems to be catty or going after a specific individual, be very careful. If anything, he was willing to give credit to people over and above what they deserved, and this is what made him such a superior leader.”

Pithiness

Jefferson was a skilled writer — he was the author of the Declaration of Independence, after all — but the ability to sum up his worldview in one sentence was not one of his “many talents,” as Berkes puts it. A sentence that seems to encapsulate his whole philosophy is likely the work of someone else.

On the other hand, Ben Franklin was, which can make his fake quotations particularly difficult to dope out. “He tended to be quite pithy [and] he tended to be quite concise, which is not something that was typical of the other people in that Founding generation, so that’s not helpful,” says Kate Ohno, associate editor of the Franklin Papers. For him, it’s the subject matter (or anachronistic word choice) that can be a giveaway. “He was an intellectually curious guy who was interested in everything, but he tended to focus more on the practical than the theoretical. He tends to address specific problems that he sees in society.”

But there are always exceptions, Ohno adds; for example, in a volume she’s editing at the moment is the Franklin quote, “I am of opinion that there never was a bad peace, nor a good war,” which defies the specificity rule.

And that’s all the more reason to think twice about a great quotation.

So how can you find what the Founding Fathers really said? Searching the Founders Online (the National Archives’ online database of their papers) is a good place to start.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com