The alert blares from the computer like a ray gun from an old cartoon: WAH-wahwahwahwah. Jonathan, a ShotSpotter analyst, focuses on one of the six monitors in front of him and zooms in on a street-level map of Milwaukee. Next to the map are what look like Christmas trees on their sides–a cluster of green sound waves.

Jonathan, who has spent nearly five years staring down these monitors, says he can tell just by looking that the pattern means gunshots. The audio seems to confirm it with a series of loud pops. The map appears to show that the sound originated from the top of a building, but Jonathan is hesitant to relay that to police on the ground. “I’m a little apprehensive to tell people to go to a roof,” he says. Instead, he simply notes gunshots were confirmed and pushes an alert to the Milwaukee police department. The entire sequence–from the supposed trigger pull in Milwaukee to the analysis at Jonathan’s desk 2,200 miles away in Newark, Calif., to the squad cars of cops back in Wisconsin–happened in under a minute.

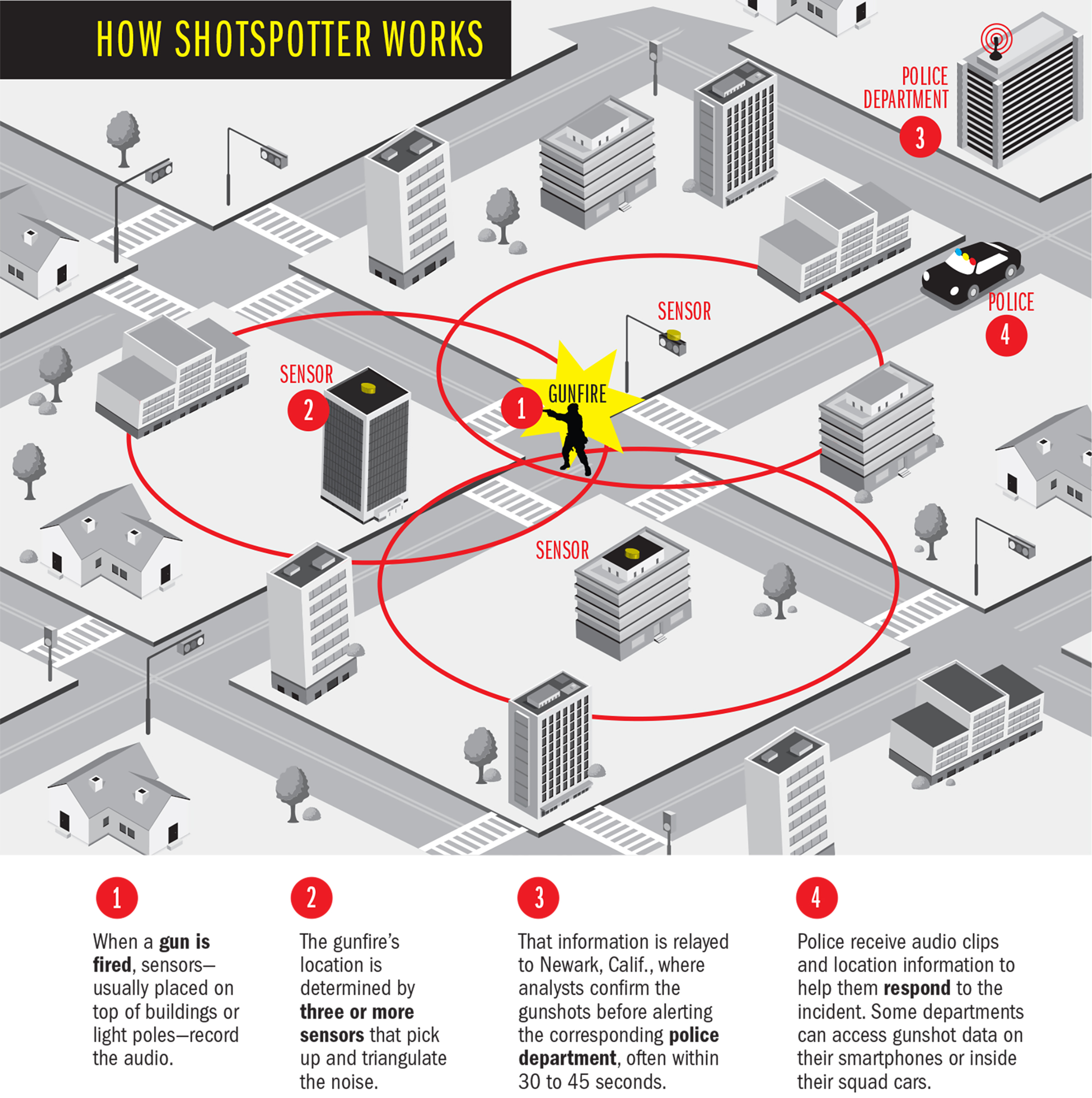

That rapid chain of events is the selling point of ShotSpotter, a small public company whose proprietary gunshot-detection technology is being used by a growing number of police departments across the nation. ShotSpotter works by installing specially calibrated outdoor microphones that pick up what CEO Ralph Clark likes to call a “boom or bang.” Those microphones are now in more than 90 U.S. cities, including New York and Chicago, and as far afield as South Africa.

Every one of those booms and bangs are routed to this cool, dimly lit room inside a Northern California business park. Here, behind a wall of tinted glass, employees like Jonathan man six computer bays, with six monitors apiece, around-the-clock. (Citing threats to employees, ShotSpotter asked that their full names be withheld.) The acoustics analysts are trained to differentiate gunfire from similar sounds like construction noise or firecrackers. When gunshots are confirmed, they send an alert that could reach the cell phone of a cop near the scene in less than a minute. “It’s a weird feeling,” Jonathan says of identifying gunfire. “It’s like you want to see one, but you don’t.”

A large monitor on the wall tracks how many incidents are flowing into the center in real time. In 2016, ShotSpotter’s analysts confirmed more than 80,000 gunshots and they expect to exceed that figure this year as they expand. In the past year, the company’s domestic network has grown more than one-third, to 480 sq. mi. New York City has announced it will increase its ShotSpotter coverage from 24 sq. mi. to 60, while seven new locations, including Cincinnati, Louisville, Ky., and Jacksonville, Fla., have recently signed on.

In June the company went public, raising $31 million in an IPO. ShotSpotter’s move to the stock market comes as crime rates have ticked up around the U.S. after a period of sustained decline. In 2016, homicides increased by about 10% across 60 of the largest U.S. cities, after a similar increase the year before. Meanwhile, many big city police departments are struggling with the effects of years of tight budgets and manpower shortages. All that makes technological innovations increasingly appealing, from automated license-plate readers that mail tickets directly to speeders to predictive software tools that aim to identify potential criminal behavior from social-media feeds.

“Police deserve credit for their willingness to adopt and experiment with new technology,” says Eric Piza, a professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and a former Newark, N.J., police officer. “It’s not surprising to me that ShotSpotter is starting to take off.”

The company’s expansion, however, raises important questions about privacy and security. The prospect of a national network of microphones, owned and operated by a for-profit company, concerns civil-liberties advocates. Others debate the system’s value. At least five law-enforcement agencies have decided against renewing their ShotSpotter contracts over questions about its cost and effectiveness.

The company says its aim is at once more modest than critics contend and grander than they may realize. Says Clark: “Police, along with communities and residents, should have an expectation that it is completely unacceptable for guns to be fired.”

ShotSpotter was founded in 1996 by Bob Showen, a physicist with a Ph.D. from Rice University and a quirky personal style (all-black wardrobe, two pairs of eyeglasses at once). At the time, Showen was working near East Palo Alto, Calif., which had one of the highest murder rates in the U.S. Showen believed he could help. He had a hunch that the same technologies used to detect earthquakes could be applied to gunshots, so he rigged a series of microphones from antennae at a radar site in Los Banos, Calif. It worked.

ShotSpotter started slow. The system was expensive for clients–$250,000–and it called for police departments to analyze the sounds themselves. The company was in just 30 cities when they hired Clark as CEO in 2010. An Oakland, Calif., native who remembers the Black Panthers patrolling the streets as a kid, Clark went on to Harvard Business School and Goldman Sachs, and later became CEO of a cybersecurity firm. It wasn’t until his second year in charge of the gunshot-detection company that he says he even held his first gun. “I don’t like being around guns,” he says.

But Clark knew balance sheets, and he realized ShotSpotter’s business model was holding the company back. Now, law-enforcement agencies pay subscriptions–$65,000 to $80,000 per sq. mi. per year–for sensors that typically sit on rooftops 30 to 40 ft. above the ground and are sophisticated enough to help analysts determine the direction a shooter is moving. Clark’s approach has more than tripled the number of cities using ShotSpotter, even as the company has continued to lose money. In 2016, ShotSpotter brought in $15 million in revenue but lost almost $7 million.

ShotSpotter’s key pitch is that gunfire is vastly underreported. Research from Jennifer Doleac, a professor of public policy at the University of Virginia, found that 88% of gunfire incidents picked up by sensors in Oakland and Washington, D.C., weren’t reported to 911. The main reason: residents don’t trust the police.

“This system is not about capturing criminals with guns in their hand,” Clark says. “What you buy the system on is denormalizing gun violence, recovering physical forensic evidence and being able to investigate gun crime down the line.”

There’s no shortage of happy customers. Agencies in Oakland, Youngstown, Ohio, and Wilmington, N.C., have all credited the system with making arrests. Police in Omaha say ShotSpotter has helped reduce gunfire by 45% since 2013.

In New York, the police department–the company’s largest client–committed to a $3 million ShotSpotter expansion. The NYPD pushes ShotSpotter alerts directly to officers’ smartphones, which they say has helped lead to a 12% reduction in response times. “It is for sure one of our most successful programs,” says Jessica Tisch, the NYPD’s deputy commissioner for information technology.

Police in Milwaukee, which has one of the highest murder rates in the country, say they recovered more than 2,600 shell casings and 45 guns related to more than 4,300 ShotSpotter alerts in the first half of 2015 alone, leading to 68 arrests. And in Denver, police commander Michael Calo says his department attributes at least 30 arrests to the alerts. “I don’t understand why any urban center wouldn’t want ShotSpotter,” he says.

One answer is in Troy, N.Y., a former industrial hub outside of Albany. Police chief John Tedesco says the system, which the city adopted in 2008, gave false alerts or failed to report actual gunfire up to one-third of the time. “We weren’t finding physical evidence,” Tedesco says. “It would sometimes take officers to the wrong location.” He says ShotSpotter tried to rectify the problems but that “officers lost confidence in it.” The department ended its contract 2012.

Even departments that use ShotSpotter acknowledge concerns about its effectiveness. In San Francisco, police say they couldn’t find evidence of gunshots for two-thirds of ShotSpotter calls between January 2013 and June 2015. Still, they say it helps identify potential problems. “We may not be making arrests, but we’re pinpointing the areas,” says SFPD spokesperson Carlos Manfredi.

Similar frustrations have plagued police in New York’s Suffolk County, where the department said less than 7% of ShotSpotter alerts between August 2012 and March 2013 were confirmed as gunshots. The county considered eliminating funding for it this year.

Clark says most of the problems are the result of misuse and misunderstanding. In Troy, he says the low accuracy rate for alerts was from an earlier era when departments were doing their own analysis. He points to a study from the National Institute of Justice that found the company’s sensors accurately identified gunfire 80% of the time.

What’s more challenging is determining ShotSpotter’s effect on crime. “The jury is out on whether it reduces gun violence or improves relationships” between police and communities, says Doleac of the University of Virginia. “There’s a lot of potential that it could do that, but there hasn’t been any rigorous evaluation of it.”

Any potential study is complicated by ShotSpotter’s refusal to release its data. Every shot registered by its sensors is owned by the company. Anyone wanting to fully analyze gunfire patterns must pay ShotSpotter for the information–a decision Clark defends on the grounds that the data is too valuable to give away.

One of the few studies of gunfire-locator systems looked at incidents in two high-crime St. Louis, Mo., neighborhoods from 2008 to 2009. It found no “appreciable effect” on deterring gun crimes. “The vast majority of departments use ShotSpotter for arriving at a scene more quickly,” says John Jay’s Piza, who used the system when he was an officer. “The problem with that is you have 30 years of research showing that police response times don’t have effects on crime occurrence or whether a crime is solved.”

ShotSpotter does publish year-end summaries, which offer a partial glimpse. Among the claims: gunfire incidents decrease 34.7% within the first two years of departments’ using the system. Other information backs up what’s clear to anyone reading the police blotter: 60% of shots occurred between 8 p.m. and 2 a.m., and the busiest hour was Saturdays between 2 a.m. and 3 a.m.

There are also the Big Brother concerns that stem from installing a vast recording apparatus across the nation’s public spaces. Clark says the sensors “only trigger when they hear a boom or bang” and that what isn’t gunfire is effectively erased after 36 hours. To privacy advocates, however, that still leaves the question of how police departments will use the data some of them buy from ShotSpotter. “What stops them from saying, ‘There was a Black Lives Matter activist having an argument, we want to get the audio from them’?” asks Jay Stanley, a senior policy analyst at the ACLU.

Back at ShotSpotter’s office-park HQ, the analysts are monitoring potential gunfire from across the country. The alerts come in almost every minute: a power-line crackle in North Palm Springs, Calif., a strange cracking noise in Newark, N.J., a pop-pop-pop in San Francisco. All apparently harmless. Then came one they were trained for: another shooting in Milwaukee, this time 19 rounds. Jonathan played the audio. A series of loud pops, one after the other, in the early evening hours thousands of miles away. He alerted the Milwaukee Police Department, and the incident was investigated. Police later said no one was injured, but no evidence was recovered.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com