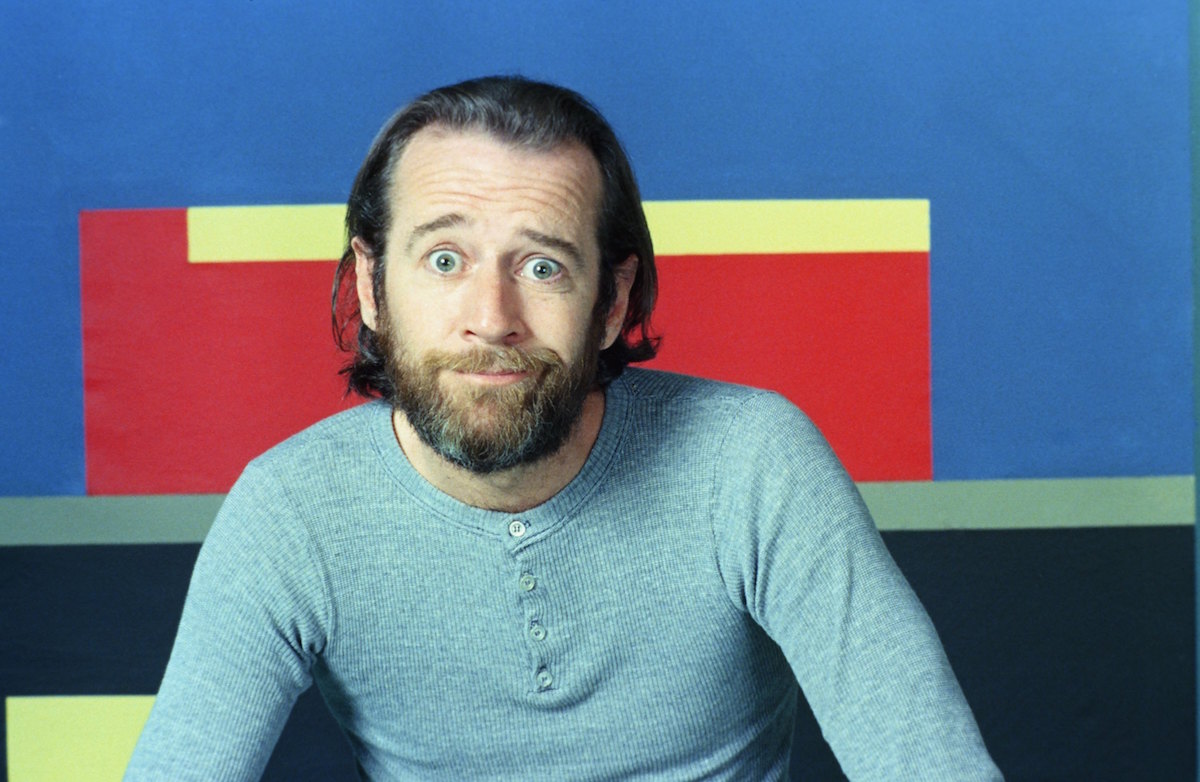

Now that they are part of comedy history, it can be hard to imagine George Carlin’s most famous routines as anything but finished products. Whether the infamous “Seven Words” from his album Class Clown (released exactly 45 years ago Friday) or the monologues from his hosting of the first-ever episode of Saturday Night Live (which returns for its 43rd season this Saturday), these routines can seem to have sprung fully formed from his mind.

But there’s plenty of physical evidence to the contrary.

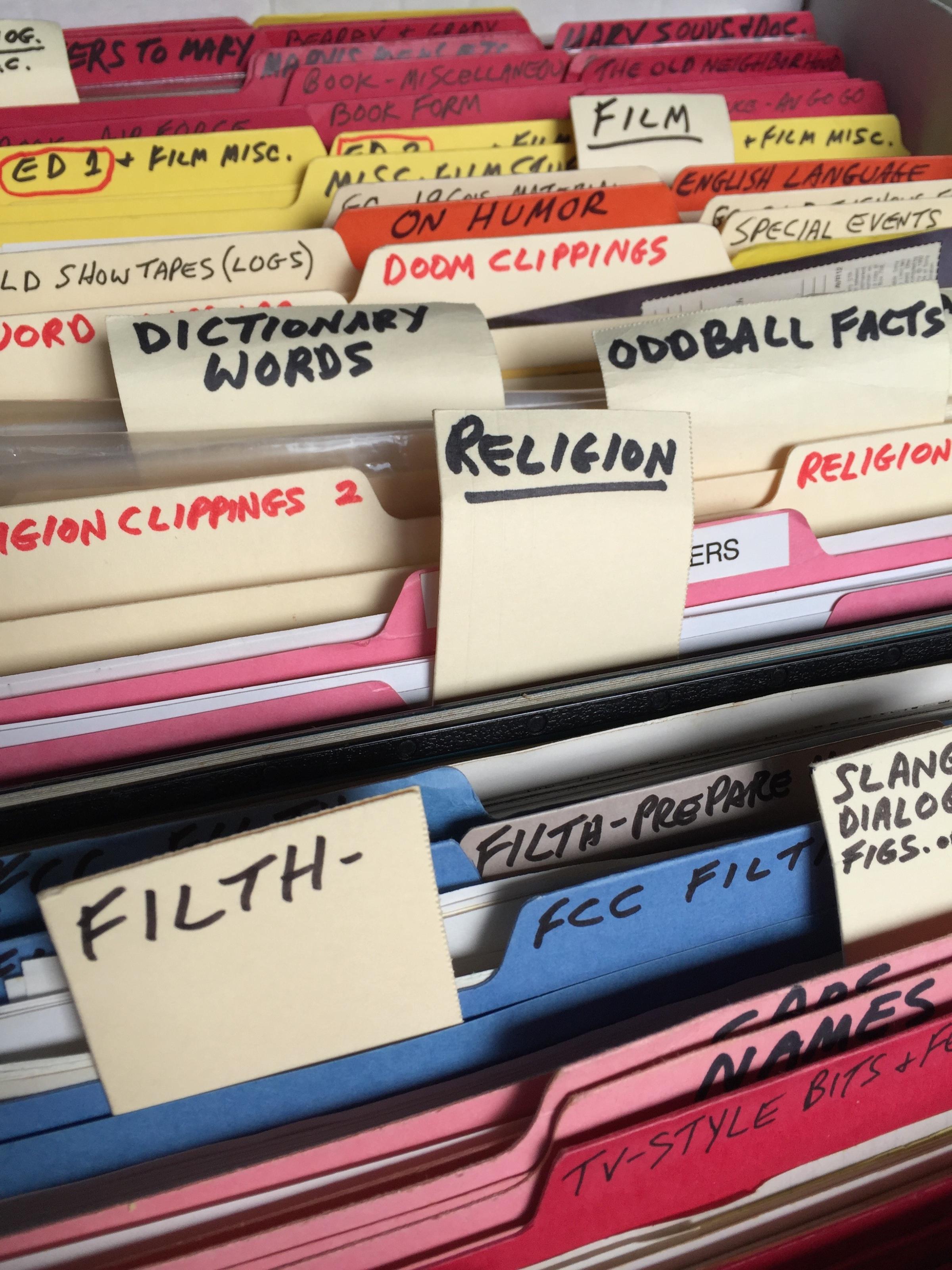

When the legendary comedian died in 2008, his daughter Kelly was left with three storage units. Among the papers and artifacts he saved were file folders that provide a glimpse into how his mind works. Those documents were acquired in 2016 by the National Comedy Center — which is scheduled to officially open in the summer of 2018 — and will thus be available for the public.

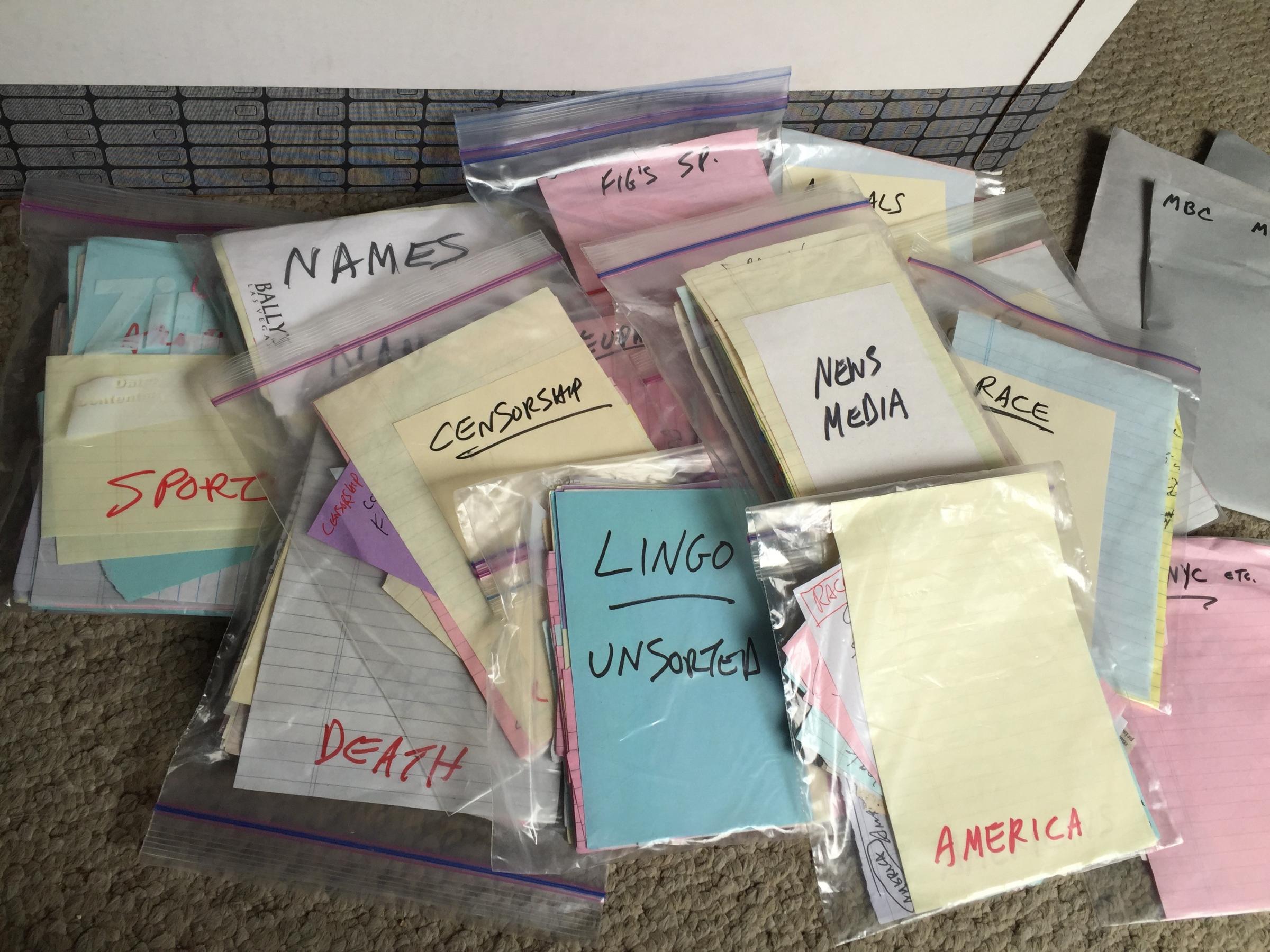

Seeing how his system worked is enough to inspire anyone not to let thoughts go to waste, notes Carlin estate archivist Logan Heftel. “A good idea,” Heftel says Carlin learned early, “is not of any use if you can’t find it.”

That motto came directly from Carlin’s boss at his first radio job, Heftel explains, along with the instruction to write down every idea he had.

Over time, Carlin formalized that system: paper scraps with words or phrases would each receive a category, usually noted in a different color at the top of the paper, and then periodically those scraps would be gathered into plastic bags by category, and then those bags would go into file folders. Though he would later begin using a computer to keep track of those ideas, the basic principle of find-ability remained. “That’s how he built this collection of independent ideas that he was able to cross-reference and start to build larger routines from,” Heftel explains.

In some cases, Heftel has been able to draw a direct line between Carlin’s notes and his finished routines. For example, a note in a bag marked “DEATH” contained the phrase “I saw him just the other day” — which is clearly linked to a joke that was included in his last HBO Special, It’s Bad For Ya. In other cases, it’s impossible for an outsider to guess what inspired the note or where it led. Nevertheless, Heftel says, the notes tend to stick close to the major themes of Carlin’s work: “big ideas, the minutia of everyday life, and then language.”

But the notes can also be seen as more than a way to “reverse engineer,” as Heftel puts it, a Carlin joke. They’re also a reminder from the comedian that time is valuable and finite. The ideas we have can slip away if they’re not pinned down, and record-keeping that can only be deciphered by the record-keeper is useless after we are gone.

“It certainly makes me want to improve my own record-keeping and organization,” he says. “I think there’s a lot people can learn not just about building a comedy routine but about approaching mortality honestly. There’s a real sense of impermanence in all of what he saved.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com