Some of the 20th century’s most defining pop music emerged from the period during which the Vietnam War was fought — and in the installment of the Ken Burns and Lynn Novick docu-series The Vietnam War that premiered on Tuesday night, that fact was made abundantly clear. The sights and sounds of Woodstock are juxtaposed with those of Vietnam, where half a million Americans were fighting at the time, and the Kent State shootings blend into the strains of “Ohio.”

But, while the role of music in stateside protest of that era is well-known — with anti-war songs like “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die Rag” featured in The Vietnam War — music also played an important role for those who were actually in Vietnam, fighting.

For warriors across time, there have always been tunes to march to, and tunes to defuse the tension. But Vietnam was special.

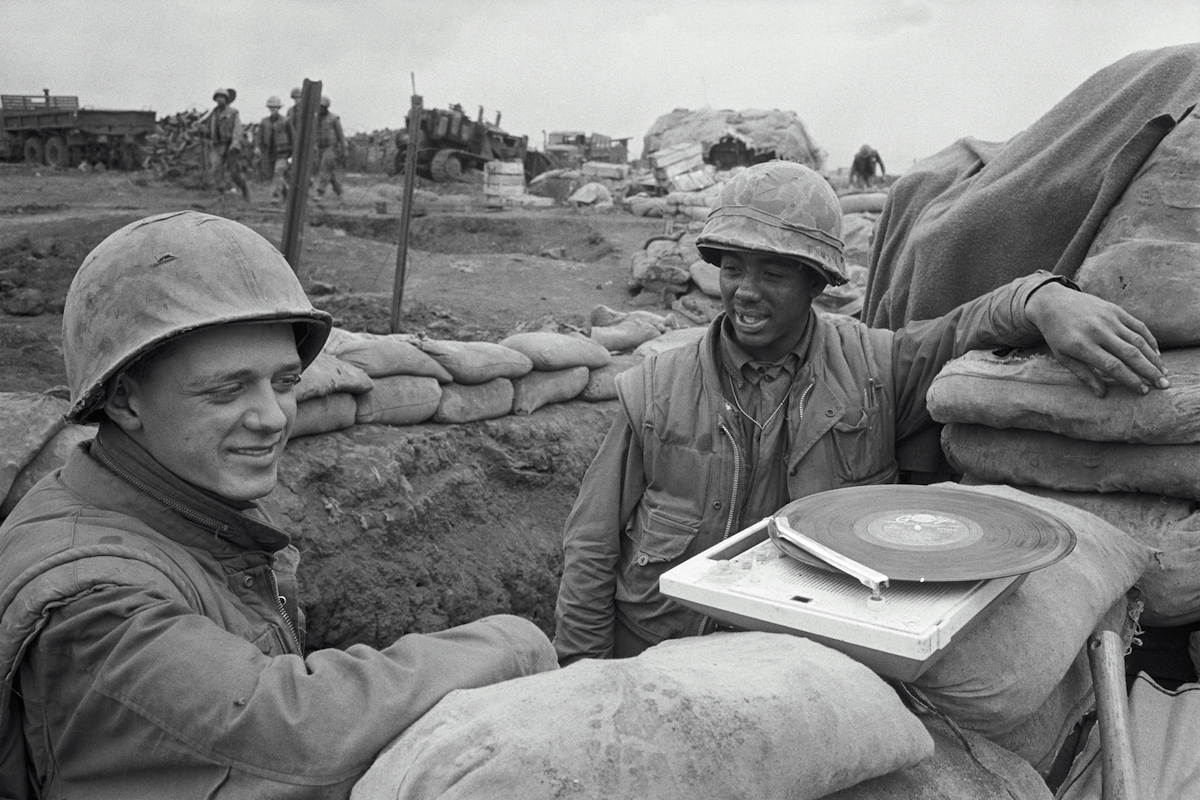

One key reason, say Doug Bradley and Craig Werner, authors of the book We Gotta Get Out of This Place: The Soundtrack of the Vietnam War, is the role technology played in getting the music to the battlefield. Between radio, portable record players, early cassette players and live bands coming to Vietnam, soldiers in that war had far more access to music than their forebears.

“The thing about Vietnam is we had modes of playing music and the military gave us enormous access because they wanted to keep our morale up,” Bradley, who was drafted into the Army in 1970, says. “There was silence in the field, but in the rear there was music everywhere. It was the same music that your non-soldier peers were listening to in America, so it was a shared soundtrack.”

Conversely, the technology was not so far along that the listening took place in solitude, the way it might today with headphones allowing each person to pick his or her own soundtrack. The diverse group of Americans who were fighting generally had to listen to music together, if they wanted to listen at all. And, Bradley and Werner note, that technological change is partly responsible for the myth that equivalent war and protest music is not being created today. “There’s a lot of very conscious music being made today. What there isn’t is great music addressing the wars that is simultaneously very popular and widely shared,” Werner says, adding that more niche music necessarily “lacks the political power [music] had then.”

Another crucial element was the draft, which meant that the war was part of daily life even for those who were not serving in the military. Awareness of war permeated the lyrics and sound of the music being produced. “Nobody was separate from it, or very few. It’s not like today where the war is being fought by a small number of people,” says Werner, who adds that in the year during which he expected to be drafted (he wasn’t, in the end) love songs like “Nowhere to Run” and “It Ain’t Me, Babe” took on new meaning for him as draft-resistance songs.

Plus, the soldiers in Vietnam and those waiting to be drafted needed that music, Bradley and Werner argue. “Music gave soldiers a way to start making sense of experiences that didn’t make a lot of sense to them,” Bradley says. Songs that spoke directly to the war were proof that people were talking about this cataclysmic event, and a way to safely express the ambivalence that many in the field felt. Even songs that weren’t directly about the war — like “Chain of Fools” — could take on new meaning in Vietnam.

There’s a myth, “consciously propagated in the 1980s,” Werner says, that the hippie protesters were an out-of-touch elite opposed to the war, whereas in fact those who were more privileged tended to support the war while the working-class combat soldiers were the ones who “really put the fear in Nixon” with their anti-war sentiments. They were the ones for whom music became a safe way to access their doubts and emotions. And that’s still the case.

Even decades after the war ended, the two found that the sense-making function of music has remained key for many veterans. When asked about the soundtracks to their war, the mention of a song like “Leaving on a Jet Plane” could trigger tears even in the most closed-in fighters. Music, Werner says, “is a truer memory.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com