No one thinks it will happen to them. We hear things on the news like: the United States is home to the largest incarcerated population in the world. We read and see the stories of formerly incarcerated people, like Piper Kerman’s experience at the Federal Correctional Institution in Danbury, Connecticut. But we never imagine that it will happen to us.

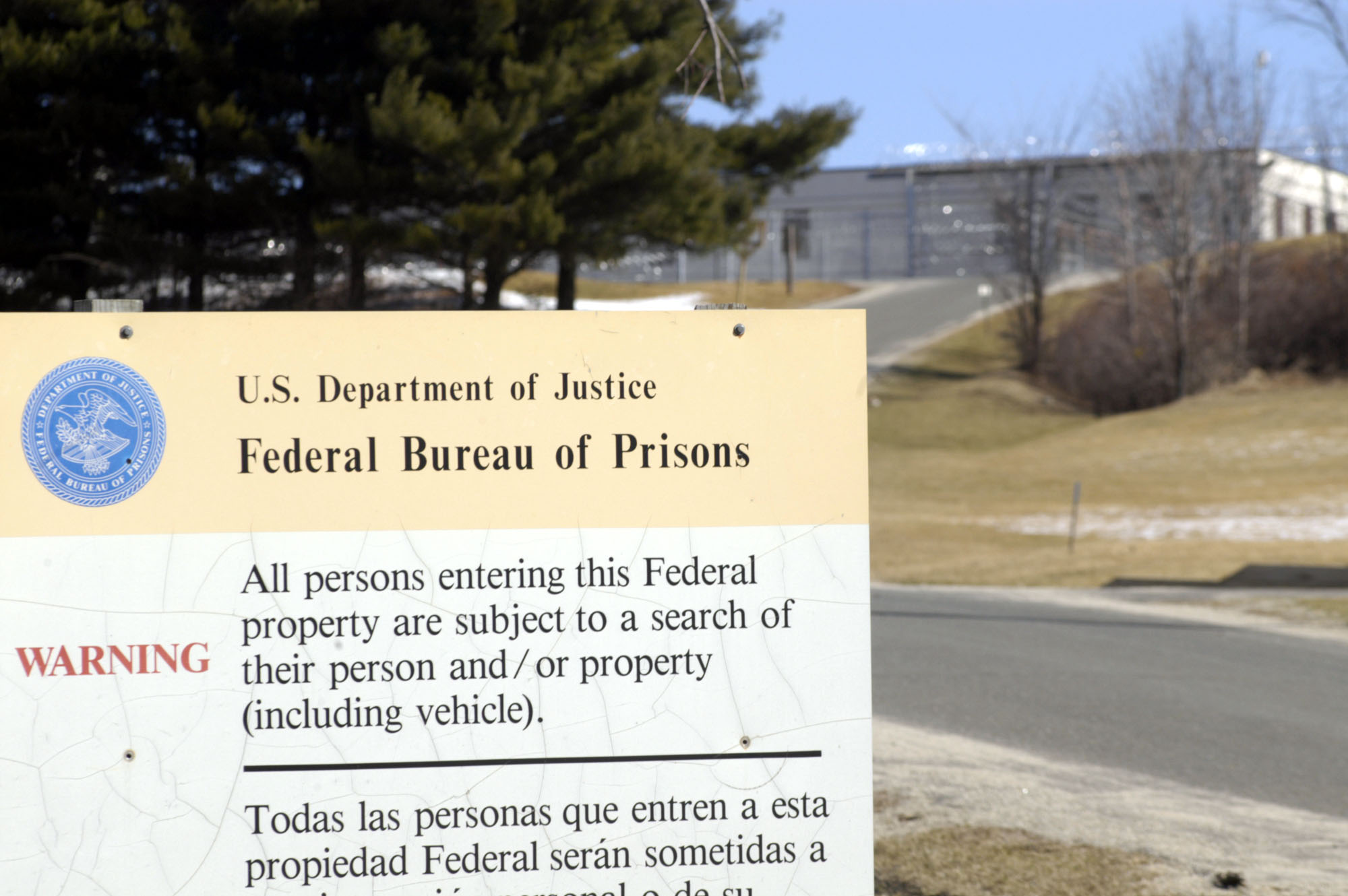

I didn’t either — until I ended up in the same Connecticut prison because of one mistake in judgment. I was a criminal defense and real estate conveyance attorney in Roxbury, Massachusetts. In 2010, I was sentenced to serve a two-year federal prison sentence for wire fraud.

I left behind my husband, adult children, parents, 12-year-old daughter and 5-month-old son, who I was still breastfeeding at the time. My new home was the prison facility, where I was warehoused with over 200 other women, crammed side-by-side in bunks piled on top of each other. There was no privacy. Male officers walked freely around our “living” areas, including our bathroom and showers. Most of the staff treated us with scorn and rebuke.

We ate 5,000 calorie meals — that were often expired — three times a day. Our living spaces smelled of fecal matter, and we had to live with inadequate feminine hygiene products. The entire experience was subhuman in an emotionally and psychologically unhealthy environment I never adjusted to.

But that all paled in comparison to leaving my children behind, which was indescribably painful. Thankfully, I was one of the lucky ones: my husband was able to drive six hours round-trip from Boston to the facility each weekend with my children so I wasn’t totally absent from their lives. That wouldn’t be possible if I was incarcerated today because Danbury now only houses men. I probably would have been placed in a facility far away from my family, possibly even as far-flung as Alabama.

Most of the women who surrounded me at Danbury didn’t have that luxury, either. I only had a 24-month sentence, yet many of my fellow prisoners had already been there for 24 years. So many of them were mothers who hadn’t seen their children at all since their arrest. (Indeed, more than 60% of women in jail or prison are mothers, and many of them are single mothers). Many attempted to parent from a prison payphone (if and when they had the money to purchase phone minutes). We were only paid, on average, 12 cents an hour for our prison jobs so we were often forced to choose between calling home to speak with your children or purchasing feminine or other necessary hygiene products or to speak to your children.

The women were forced to live year after year in this prison while their children struggled to survive without them. Some mothers lost children to gun violence but weren’t permitted a temporary release to attend the funeral. I will never forget the sound of a woman on the prison bunk next to me, sobbing at 3:00 a.m. over the loss of her child.

As an outlet for the pain of being separated from my family, I used the outdoor track to run five miles a day. Without that daily run, I could have easily ended up in the long pill line. More than half of the women incarcerated take some form of psychotropic medication during their time behind bars (that’s compared to only 20% of male prisoners.) During my mental saving jogs, I would listen to my commissary-purchased radio and would hear that many media outlets were finally discussing mass incarceration.

But they were missing the point. They were only talking the drug war and how the United States is the largest incarcerating country in the world. What I wasn’t hearing was about the real issues that incarcerated women — the fastest-growing segment of the prison population — face every single day.

So, my sisters inside and I decided that we wanted to do something about the latter. In the prison yard, we created and held the first meeting of Families for Justice as Healing (FJAH), with the goal to raise public awareness of women as the fastest growing incarceration population and to use our voices to create a more accurate portrait of who we are, what we had learned and what we could contribute to this dialogue.

FJAH’s work continues in Boston and has led to our national movement and organization, the National Council For Incarcerated and Formerly Incarcerated Women and Girls. We work to end incarceration of women and girls and to shift from a criminal legal system focused on punishment, to a system based on human justice.

My experience taught me that incarceration is not the solution for what leads a woman to a prison bunk. For real, meaningful reform to be accomplished, formerly incarcerated women must be in the lead to create the dramatic change that needs to happen. It’s great that some lawmakers and leaders are now taking up that task.

Late last month, the Bureau of Prisons announced that prisons would be required to provide feminine hygiene products free of charge. In July, Democratic Sens. Cory Booker, Elizabeth Warren, Kamala Harris and Richard Durbin introduced the Dignity for Incarcerated Women Act, which would require the Bureau of Prisons to consider the location of kids when placing women in prison facilities, ban the shackling of pregnant women and make phone calls free for prisoners, among other provisions.

But we still have a long way to go. I urge lawmakers to swiftly pass the Dignity For Incarcerated Women Act, which hasn’t seen any public progress since it was referred to the Committee on the Judiciary in July. Policy makers need to focus on expanding alternatives to incarceration, such as Primary Caretaker model legislation, to stop the flow of sending more people unnecessarily to prison.

We must turn the discussion upside down and instead of focusing on “re-entry” seriously think about what we need to do for “no-entry.” We must acknowledge the centrality of violence and sexual abuse of women and girls, racism, poverty and homophobia as drivers of the criminalization and incarceration of women and girls. If we do not, we will just be tinkering around the edges. Only when we step back and look at the complex big picture, will we be able to begin to undo some of the immeasurable harm that has been done and invest in resources to help communities begin to heal and thrive.

Andrea James is the founder of Families for Justice and Healing and the founder and Executive Director of the National Council for Incarcerated and Formerly Incarcerated Women and Girls.

Motto hosts provocative voices and influencers from various spheres. We welcome outside contributions. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of our editors.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com