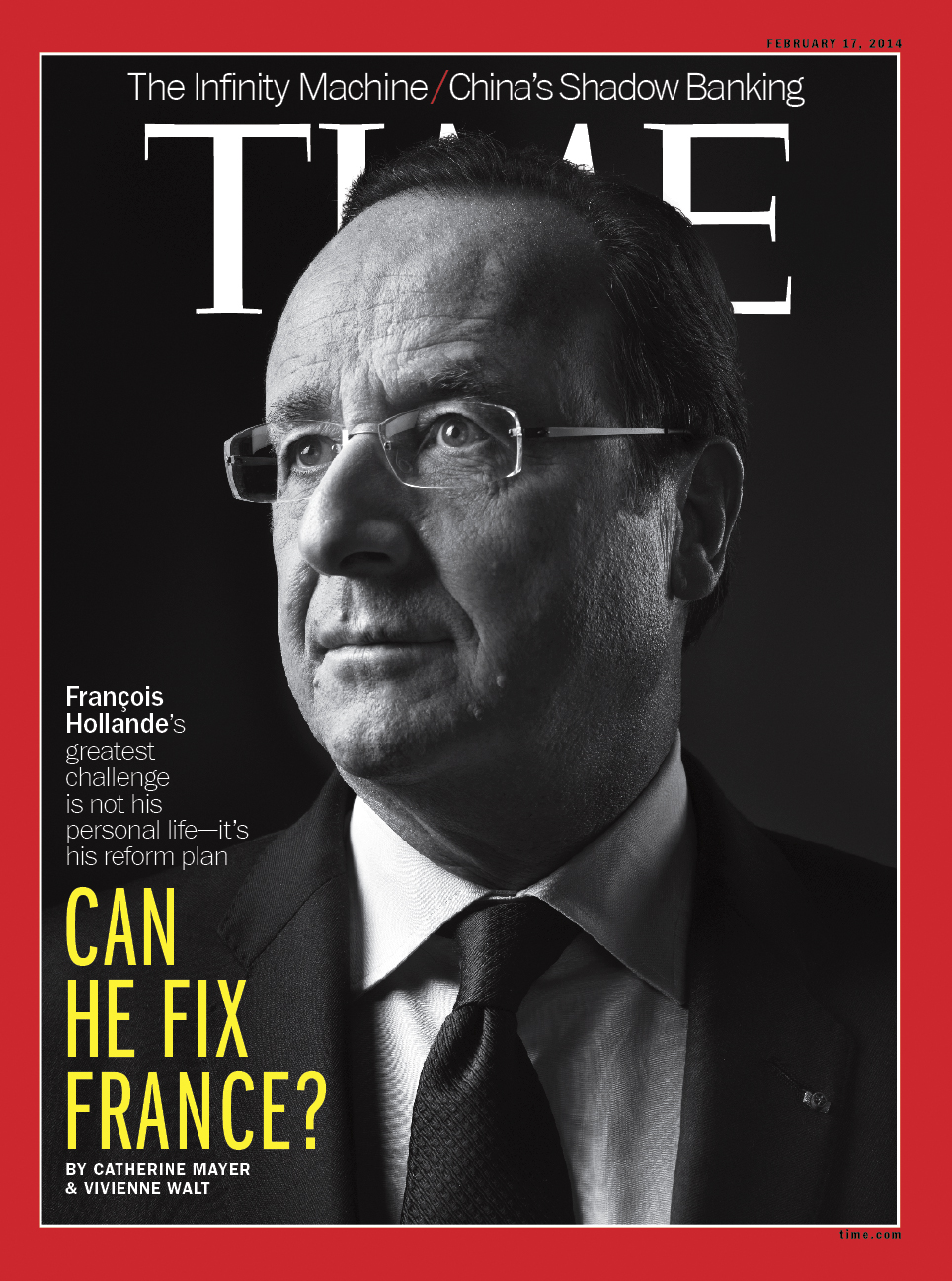

François Hollande has been known to spend nights elsewhere, but his official residence is the Élysée Palace. Here, in its 18th century splendor, he sat down with TIME on Jan. 25 in a discussion that ranged widely, from the malaise of the French economy to more personal travails. His approval ratings had dipped to record lows. Later the same day, Hollande would confirm his split from his official First Lady Valérie Trierweiler.

Next week Hollande arrives in Washington solo, kicking off an official state visit without the baggage many expected him to bring. French leaders have frequently tussled with their U.S. counterparts, and Hollande arrives in the wake of Edward Snowden’s game-changing revelations about America’s habit of snooping on her friends, including France. Hollande calls this “a difficult moment, not just between France and the United States but also between Europe and the United States.” And, he adds, it has been uncomfortable for Americans forced to confront “practices that should never have existed.” But, he says, there is no residue of bitterness between him and President Obama. Indeed he sees an opportunity “to build a new cooperation in the field of intelligence … We need intelligence services to fight against terrorism, but they have to respect the principles of good relationships between allies and protect personal, confidential data.”

He even goes so far as to hold up the U.S. as an example to his own compatriots as he attempts to persuade the French people to accept his new-minted economic-reform program that will mean some pain before the gains. “The first time that I went to the United States was in 1974,” he says. “I was 20 years old. America was in crisis. The dollar was at a low. The Watergate scandal had already erupted. And I still remember this vision I had of New York, which was a huge, fascinating city, dirty and violent. And I’ve been to the U.S. regularly, but what impresses me most in this large nation is its capacity to overcome hardship and return to the heights.” He hopes to emulate that example but recognizes he’ll need to achieve results fast. “It’s the timescale that we have to shrink,” he says, using a familiar English slogan to make his point: “Plus que ‘yes we can,’ ce devrait être ‘yes we can faster.'”

The new issue of TIME carries an in-depth profile of Hollande and his plans for France and its worldwide role, based on that exclusive interview. The President’s priority at home is to revitalize the country’s torpid economy by reducing the cost of employment to businesses and trimming the bloated French state, a sharp change of direction for a politician elected on a Socialist ticket and one broadly welcomed by anyone with an interest in French prosperity — and that’s a large part of the interconnected world. Yet Hollande has no desire to trim the global role he sees for France. Syrian strikes may be on the back burner, but French troops have been active in Mali and the Central African Republic. The U.S. and U.K., scarred by their experiences in Iraq and Afghanistan, are battle-weary. France, or at least its President, seems less so. “Even during this very difficult period, I wanted to demonstrate that France could assume its full responsibility on a global scale, no matter the area: human, financial, political,” says Hollande.

Of his aspirations on Syria, he says: “Our only goal is to strengthen the opposition and to avoid the dilemma whereby we only have the choice between Bashar Assad and al-Qaeda.” He says the failures of the West led to this dilemma. “In August 2012, the international community should have been far more determined in dealing with the Bashar Assad regime,” he says. “He was weakened in political, military and personal terms. He had been abandoned by part of his general staff. The massacres had not reached the horrific level that we are now seeing.” The delay undermined the opposition and allowed al-Qaeda to gain purchase. Hollande had been poised to unleash air strikes on Syria aimed at weakening the Assad regime in September, when a last-minute swerve by President Obama led instead to a fresh bout of diplomacy. In a deal brokered in part by Russia, Syria began dismantling its chemical-weapons capacity and Hollande stood down his strike force. “Everything was ready for the day that we’d chosen,” he tells TIME. “President Obama decided to go to Congress. But our threat to strike convinced the Russians and the Syrian regime to agree to surrender their chemical weapons. So it was a success for us. It was not as has been reported a victory for the Syrian regime.”

History is often made by accident. Hollande’s own route to the presidency was full of surprising twists. His first two years in office has yielded quite a few shocks, not least his emergence as a figure of interest to the tabloid press. He is loath to answer questions about his private life, saying simply that it is “always at some moments a challenge, and that must be respected. In my own personal situation I can’t show anything.” And he tries not to show anything, apparently impassive as he answers the question, but flushing visibly. He wants to wrest the conversation back to important things like fixing France and shoring up the country’s global influence. His U.S. visit will be a good place to start.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com