In recent weeks, as Americans across the country have engaged in debates about how the Civil War period is publicly commemorated, a quieter battle over a related question was finally put to rest.

On Aug. 30, 2017, Senior United States District Judge Thomas F. Hogan answered an old question for Cherokee Freedmen — the descendants of people who were enslaved by members of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma — who have been fighting for their tribal citizenship since the early 1980s.

In the case of The Cherokee Nation V. Nash, et.al. Judge Hogan looked at whether an 1866 Treaty — which stated that people who had been emancipated by the Cherokee would, along with their descendants, “have all the rights of native Cherokees” — ensured continuing citizenship rights for the people whose ancestors were freedmen included on the Dawes Roll (the U.S. government’s official list of tribal citizens) between 1898 and 1914. In the case, the Cherokee Nation had held that their revised constitution, which had expelled the Freedmen from the tribe in 1983 on the premise that they were not “blood” Cherokee (though many of them are of Black-Cherokee ancestry), held more legal weight than the 1866 treaty. However, the judge ruled that the constitution does not negate the Freedmen’s treaty rights granted to their forebears at the end of the Civil War. In other words, Cherokee Freedmen are Cherokee.

While the case of the Cherokee Freedmen has continually made headlines during the past decade, the story of American Indians as enslaved people and slave owners remains a relatively unknown aspect of American history.

Slavery was a reality of indigenous life in the Americas prior to the arrival of Africans and Europeans. As Christina Snyder explains in her book Slavery in Indian Country: The Changing Face of Captivity in Early America, “captivity” was “widespread, and it took many forms.” But, as Snyder explains in tracing the history of Southern Indian captivity to the pre-Columbian era, the advent of European colonialism meant that Indians found themselves thrust into a global economy underscored by a racialized system of human trafficking for profit. “Slavery was not peculiar to indigenous societies,” where captives were prisoners of war obtained from enemy tribes, Snyder notes, but “the [commodified] form that slavery took in the antebellum South and elsewhere in the colonial Americas,” was new.

With the introduction of a rigid slave system to North America, which exploited both Indian and African bodies as human commodity, indigenous people became part of that economy, on both sides of the transaction. For example, in his book The Westo Indians: Slave Traders of the Early Colonial South, Erin E. Browne describes how the Westo Indians from the Northeast captured enemy tribes to trade to the English Virginians for guns, ammunition, metal tools and other goods. And in the west, as highlighted by the scholar Andrés Reséndez in his book The Other Slavery, the buying and selling of Indians—even though it was illegal and California entered the Union as a free state—was “common practice” in the years after the Mexican-American War.

While the myth that African slavery replaced Indian slavery continues to persist in our society, “Indian slavery never went away,” contends Reséndez, “but rather coexisted with African slavery from the sixteenth all the way through to the late nineteenth century.”

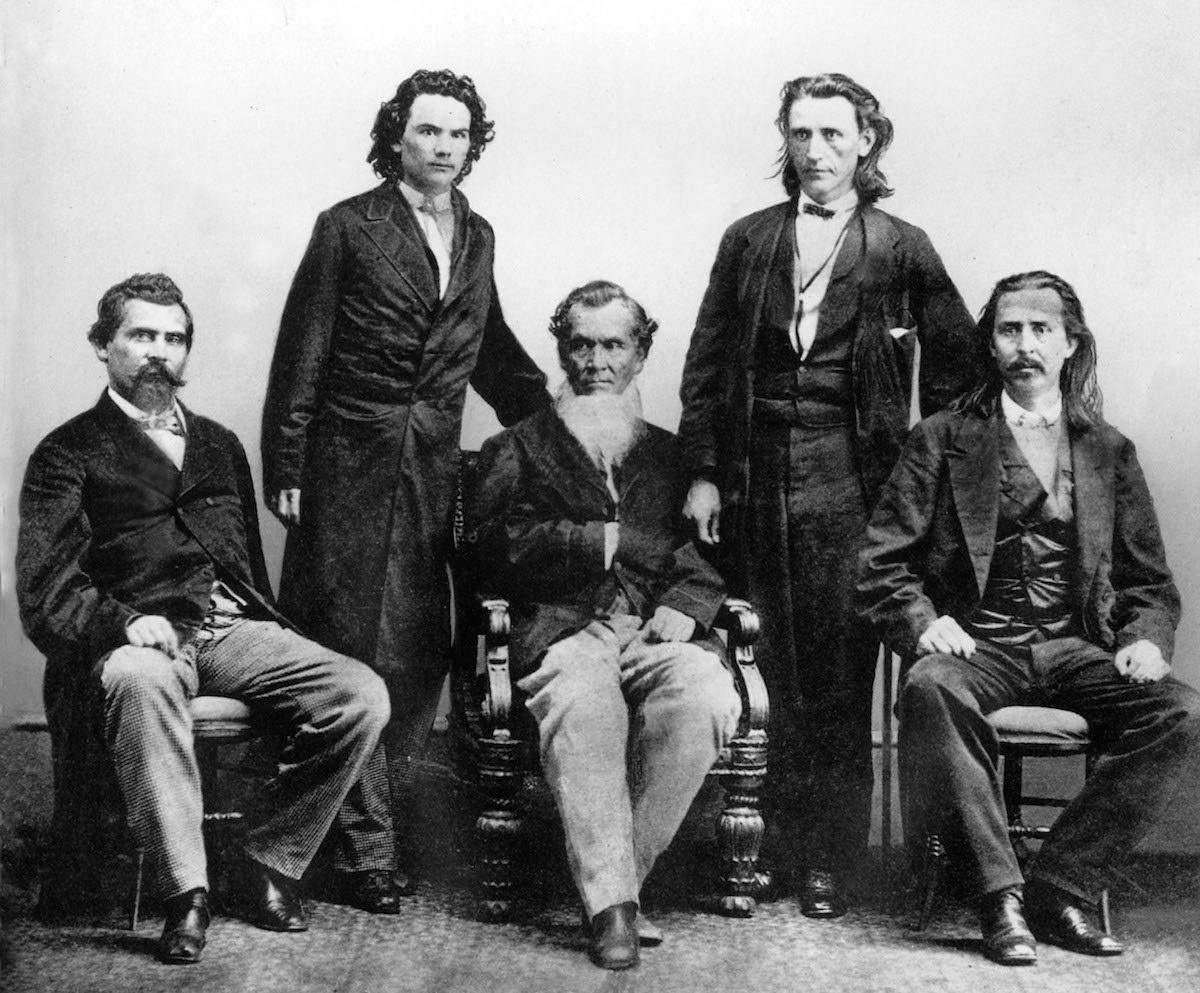

The Five Tribes — whose original homeland was located in the southern interior, in an area bounded by the Cumberland River to the north and the Mississippi valley to the west, and who included the Cherokee — adopted racialized chattel slavery in the late 18th century. Southern whites urged them to participate in the enslaving of black people as a part of the Federal Government’s Indian “civilization” effort. Hence, the name “The Five Civilized Tribes.” The Cherokee Nation exceeded their counterparts in embracing white southern slave culture and profited the most from slave ownership. By 1809, there were 600 enslaved blacks living in the Cherokee nation; by 1835, the number increased to 1,600.

In her book The House on Diamond Hill: A Cherokee Plantation Story, Tiya Miles tells the intriguing story of The Chief Vann House, located on a vast plantation in northeast Georgia. It was named Diamond Hill in 1801 by its owner James Vann, the wealthiest and “reportedly cruelest of Cherokee slave owners,” who owned at least 100 slaves. Diamond Hill later fell into disarray as a consequence of Andrew Jackson’s forced Indian removal, but the Vann family continued to prosper as slavery in the Indian Territory (now the state of Oklahoma) proved far more profitable to the tribes than it had been in the Southeast. By 1860 there were 4,000 enslaved blacks living in the Cherokee Nation alone.

Although the Cherokee Nation had resolved to remain neutral at the outset of the Civil War in April 1861, by October they entered into a treaty to join the Confederate cause. The reason, they argued in that document, was that the “Cherokee people had its origin in the South; its institutions are similar to those of the Southern States, and their interests identical with theirs.” In addition, they painted the war as one of “Northern cupidity and fanaticism against the institution of African servitude; against the commercial freedom of the South, and against the political freedom of the States.”

But by the following fall, with the Nation sorely divided as thousands of Cherokee fled to Union lines, the Cherokee Council abrogated its treaty alliance with the Confederacy. On Feb. 19, 1863 — shortly after Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation went into effect — the Cherokee Nation issued An Act Providing for the Abolition of Slavery in the Cherokee Nation, which called for “the immediate emancipation of all Slaves in the Cherokee Nation.” In a treaty ratified on July 27, 1866, the Cherokee Nation declared that those Freedmen “and their descendants, shall have all the rights of native Cherokees.”

It is these words the Freedmen held onto during their long legal battle. Marilyn Vann, a descendant of the James Vann family and one of the plaintiffs in the lawsuit, expressed that idea to NPR after the decision was issued. “All we ever wanted,” she said, “was the rights promised us.”

Historians explain how the past informs the present

Arica L. Coleman is the author of That the Blood Stay Pure: African Americans, Native Americans and the Predicament of Race and Identity in Virginia and chair of the Committee on the Status of African American, Latino/a, Asian American, and Native American (ALANA) Historians and ALANA Histories at the Organization of American Historians.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com