Larry Burrows was a seasoned veteran of the Vietnam War when, in early 1968, he met 12-year-old Nguyễn Thị Tròn.

Operating out of Saigon, the southern Republic of Vietnam’s capital, the photographer had been covering the conflict for LIFE magazine since 1962. He shadowed American troops, documenting ferocious firefights, surviving hours in the air with helicopter-gunship crews, and freeze-framing harrowing moments of bravery and despair, exhaustion, and appalling violence in combat zones.

Though much of his best work had been shot in the thick of the action, he had come to be haunted by the trauma visited upon the Vietnamese people he described as non-political, “simple and hardworking.” Most, he believed, were steamrollered by both the South and the communist North to “bear pain in silence.” Burrows noted their stoicism with awe.

“I was walking the streets of Saigon, as I’ve been doing for six years, thinking I’d never really told of the misery and suffering,” the photographer later recalled of meeting Tròn. “Round a corner, in a Red Cross compound, two Vietnamese children were rocking back and forth in a swing […] Walking along the fencing I could see their small bodies rocking to and fro. Now I had a clearer view. They were not the same as any other two youngsters, for they only had one leg between them, and it was Tron who propelled the swing.”

Tròn had lost her right leg just months earlier, in October 1967. The inquisitive youngster had been collecting firewood and foraging for plants in a Viet Cong-infiltrated no-go area – a free-fire zone in which American troops had clearance to shoot to kill anything that moved. The rustling of branches, perhaps the pale flash of Tròn’s conical nón lá straw hat, led to her being spotted from above, and the metallic chak-a-chak-a-chak-a of a U.S. helicopter’s machine guns rattled out.

Tròn’s injuries resulted in amputation of her leg below the knee.

A self-confessed “adventurer by nature,” Burrows regarded US-supported South Vietnam’s fight against the North as virtuous (he was “rather a hawk,” he would write, who “generally accepted the aims of the US and Saigon”). His meticulous, unflinching approach to getting the picture resulted in arguably the most searing visual record to emerge from the Southeast Asian war.

But Burrows also knew the full story of the conflict was not to be found in a monsoon-flooded foxhole, and that thousands of modest battles were being fought across Vietnam every day. He wanted to tell that story, and to photograph a personal but no-less-crucial fight in the war that had raged for more than a decade.

Burrows and his interpreter approached the children in the swing, asking Tròn where she lived. “I felt then that if I could only show the sufferings of her people through her eyes,” the photographer said, “this could speak of the huge losses the Vietnamese have suffered over the last 25 years.”

A few weeks, perhaps a month later, 41-year-old Burrows rocked up to the tumbledown hamlet of An Điền in the rural district of Bến Cát in Bình Dương Province, less than 30 miles north of Saigon.

And so began an unlikely friendship between one of Vietnam’s most battle-hardened photojournalists and a war-damaged child.

‘Tears ran down my cheeks’

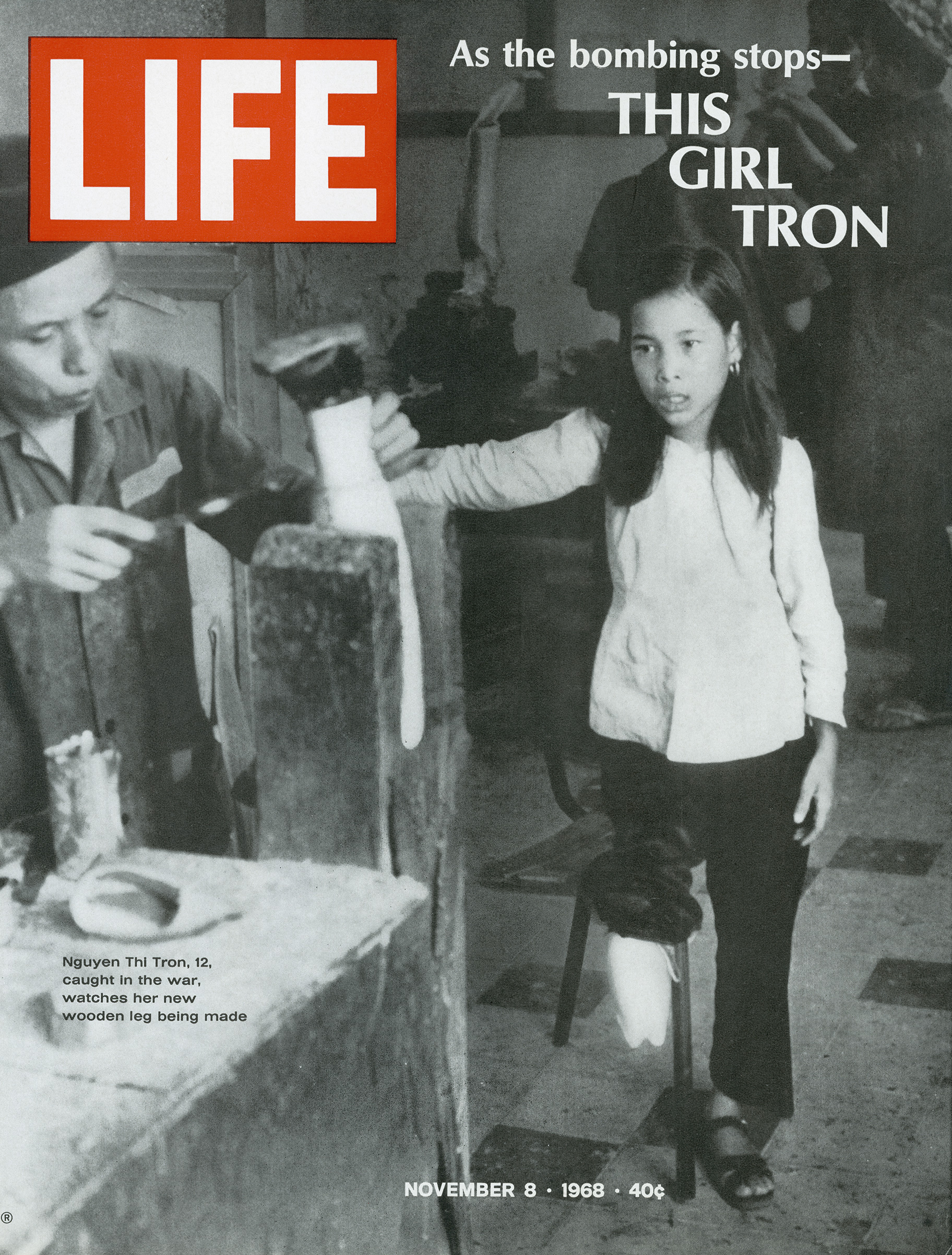

Burrows’ cover of LIFE magazine on November 8, 1968, during a relative lull in hostilities, featured the maimed youngster and the headline: “As the Bombing Stops – This Girl Tron.” In the cover picture, she balances on her surviving leg, watching nervously as a Saigon workman fashions a crude wooden limb at his bench.

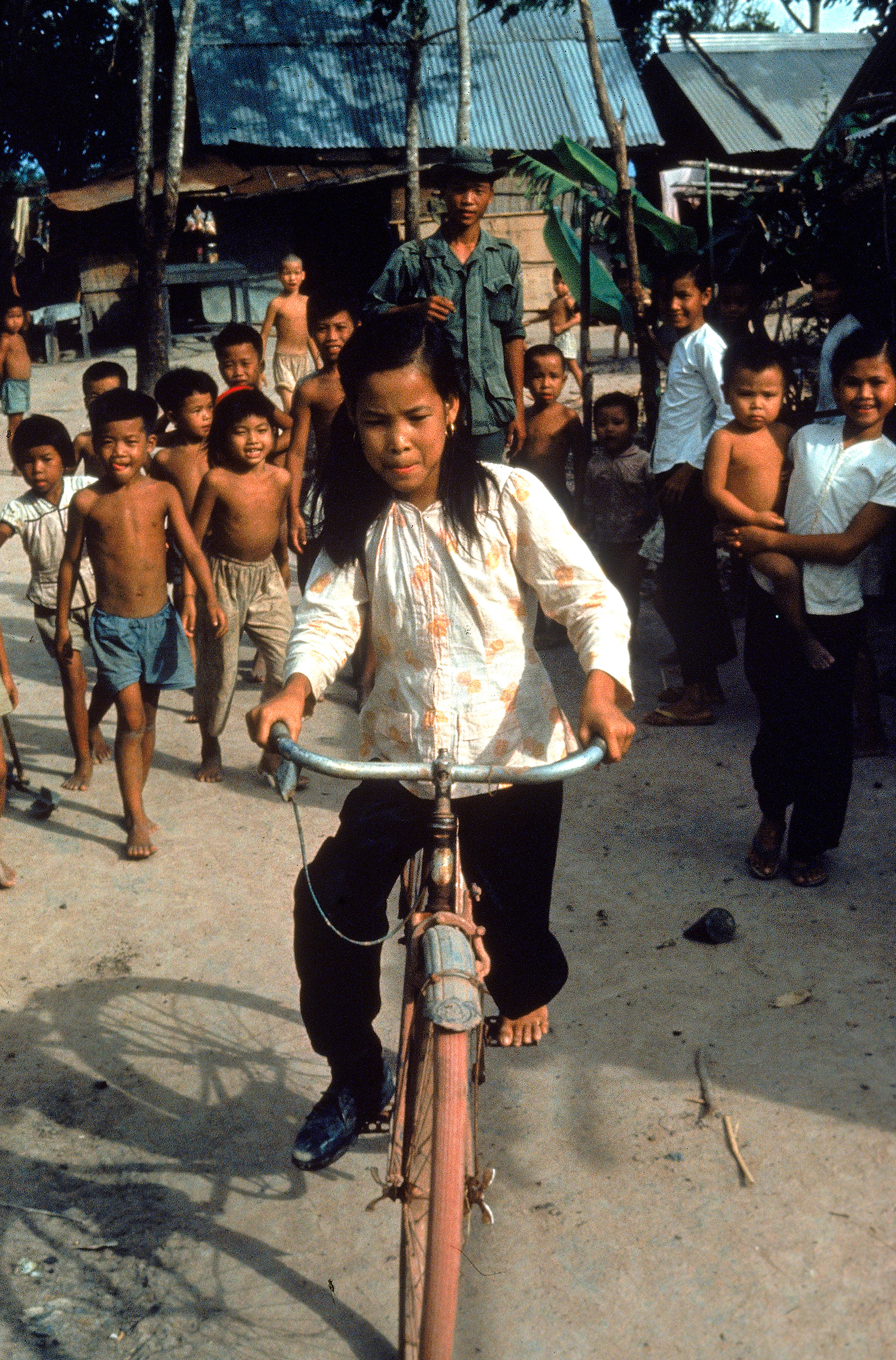

Burrows had visited Tròn and her family a number of times in ’68, documenting her rehabilitation: the fitting of her primitive prosthesis, learning to walk and ride a bicycle again, returning to school and sorting vegetables beside the family’s dilapidated shack, just one of the village homes that LIFE’s Saigon bureau chief, Don Moser, described as “flimsy constructions of corrugated iron, cardboard and the universal pop art of the country, sheet metal stamped with beer can labels.”

Burrows’ pictures were published over 12 pages and captioned in his own words. One description recounts Tròn trying her new leg for the first time: “Then it was her turn to be fitted and she was frightened. She buried her head against a post as a workman shaped a leg from wood blocks, and then sat while a plaster mold was squeezed against her stump. Finally she could stand. She balanced with the help of crutches, bit her lower lip and let the crutches be taken away. I won’t forget that moment. Tears ran down my cheeks, but I blinked so I would not miss seeing any of her joy and excitement.”

Many affecting images came out of the Vietnam War. One of the most enduring is Nick Ut’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 1972 image of naked and burned nine-year-old Phan Thị Kim Phúc fleeing a napalm attack in Trảng Bàng (less than 10 miles from where Tròn was shot).

Ut’s picture is one of the most globally recognized of the 20th century, and Phúc became feted as “the girl in the picture.” Her story since then is well known: in the 1992, she and her husband secured political asylum in Canada, and she has since become a mother, a United Nations goodwill ambassador and an activist highlighting the plight of children affected by war.

But what of Tròn? What has been the fate of the girl in Larry Burrows’ pictures?

‘I was hit’

Saigon was renamed Ho Chi Minh City, in honor of the North’s revolutionary leader, in 1976, a year after the war’s end. Heading northeast from that city today, a three-hour drive passes through Củ Chi, home of the underground network of hidden tunnels that were the Viet Cong’s base of guerrilla operations for the Tết Offensive in early 1968, as well as the US military hospital to which Tròn was taken after being gunned down.

My destination is Suối Đá commune in the Dương Minh Châu district of Tây Ninh province, which borders southern Cambodia. The land here is sun-scorched, road-kill flat and agricultural, with star apple, rubber, sugarcane, peanut and maize being popular crops. Perhaps a kilometer down a side road of compacted red earth hides a small shack of weathered wood, bare brick and concrete. The shack is a community convenience store sparsely stocked with candy and potato chips, basic medicines, stationery and everyday essentials.

The store also provides seamstress services, and a sewing machine takes pride of place at the road-facing service hatch. Tròn sits at a concrete table out front, shaded by leafy banyans. Cicadas thrum in the branches and roosters scrabble among roots that have raised the land, causing flooding to the shop with each rainy season.

Petite and slender in build, her wavy black hair only flecked with gray and pulled into a ponytail, Tròn, now 62, wears loose-fitting black pants and a short-sleeved floral blouse – the practical, no-nonsense uniform of rural women across Indochina. She lives with Chi, her bubbly 30-year-old niece whose smile sparks readily beneath her nón lá, and who welcomes us with chilled coconut water.

Tròn recalls the day her life changed.

She lived with her farming mother and father, two sisters (one older, one younger) and little brother within the 120-square-mile communist stronghold known during the war as the Iron Triangle. Located between the Saigon River to the west and the Tinh River to the east, and about 25 miles north of Saigon, the area’s strategic position made it the scene of much fighting, and destruction of their village saw the family evacuated to An Điền, close to a republican army base at Lai Khê, also headquarters of the U.S. Army 1st Infantry Division.

“My family was very poor and my father went to the forest every day to collect firewood to sell in the village,” remembers Tròn, who speaks in a lilting whisper and whose movements are slow and measured. “My mother worked for whoever would hire her. We lived day to day, my parents doing whatever they could.”

Though villages in the area were under republican control by day, the situation was less cut and dried after dark, with Viet Cong moving around freely. There was often confusion as to who was in charge.

“In that area, there were two zones: the Liberated Zone, which belonged to the communists, and the Republican Zone, controlled by the South, so people had been split up in the region,” Tròn says. “One day, Republican soldiers said we could go into the liberated area, maybe to see relatives, and I went with two friends, children like me, to collect wood. One of my friends had a bicycle. My other friend and I ran behind her.”

The children were exploring when came a shrill warning to flee. “An old lady shouted that a helicopter was coming from the Saigon River, and that we should leave quickly, so my friends and I started running back,” Tròn remembers. “I’d only run a short distance when shooting from the helicopter started. I tried to hide among the trees, but I was hit.”

One of Tròn’s young companions was also shot, in the abdomen, and later made a full recovery. LIFE reported that a man cutting wood and loading an oxcart in the area was killed by fire from the helicopter.

“I felt no pain at first; my leg felt numb,” says Tròn, whose 87-year-old mother, Nguyễn Thi Xuân, lives close by and sways in a hammock outside the store. “I had grown up in the liberated area, and older people had told me that if I was shot by the Americans I might die, so I got up and tried to run. I was so scared, but when I tried to run, I couldn’t. My leg would not work and I cried out for my mother.”

The helicopter landed and the soldiers realized their mistake, gathering up the wounded girls to evacuate them to hospital. “That was when I felt very great pain. I did not know how to stop it and kicked at the American man treating me.”

Hearing of the shooting, Tròn’s mother hurried to the restricted area, finding dried blood and learning that children had been gunned down, perhaps killed. She headed for the US army base. “I spoke to the interpreter there. I asked if she could help me find my daughter,” the older woman recalls, her sun-weathered face suddenly animated. Tears well in Tròn’s eyes as she listens to her parent’s account, and she turns away to hide her sadness. “They called all the hospitals in the area, they could not find her,” her mother says, “but they said there was a hospital where they had not checked, at Củ Chi, the army hospital of the Americans.”

There, Tròn was alone. “Many people came and asked me who I was, what I did, what I’d been doing there, who I was visiting,” she remembers, the desperation of that moment, 50 years ago, entering her voice. “I tried to answer but I was in so much pain. I just wanted the pain to stop, but they kept questioning me.”

And Tròn remembers discovering the loss of her limb while in a hospital bed. “My leg started to itch, so I tried to scratch it with the other one,” she says. “That’s when I realized they had cut off my leg, and I cried.”

Reaching the army hospital was difficult for Tròn’s mother. Movement in the area was restricted, and she waited days for the only bus. “When I found her, she just cried and cried,” she says, adding that her daughter was tormented by the thought that, coming from a peasant family, she would never be able to work. “She said, ‘I can no longer have a life, I am useless, I will die.’ I tried to reassure her, telling her I would do my best to earn a living so that she could grow up. I told her, ‘I will never leave you. I will always take care of you.’”

A group of pictures in Burrows’ LIFE essay show Tròn fooling around with young friends, and taking on “the role of a comic to hide the sadness.” His caption reads, “Like her country, Tròn can never be the same again after the war is over. She makes the best of it even when she falls while playing hopscotch, turning it into a clownish joke. But sometimes the sadness appears. ‘I will stay with my mother until her dying day,’ she told me. ‘I have only one leg. I can do nothing.’”

Tròn’s disability, and how that impacted upon a woman of her generation and background, means she never found a husband or had children of her own.

‘The signature photographer of the war’

Though young Tròn came to refer to Burrows as her American father (to the unworldly Vietnamese child, all Caucasians were Americans), Burrows was British.

Born in London in 1926 to a truck driver father and housewife mother, Henry (“Harry”) Frank Leslie Burrows left school at 16. Keen on photography, and after stints working in the darkrooms of the Daily Express newspaper and the Keystone photo agency, he joined LIFE’s London bureau as an errand boy-cum-apprentice. Burrows was called Larry to avoid confusion with another Harry in the office.

Increasingly adept with a camera, Burrows progressed to shooting everything from the Suez crisis and a French starlet (“Brigitte Bardot on a London shopping sally”) to Ernest Hemingway touring Spain with its greatest bullfighters and the 1962 Indo-China War. But though Life sent the photographer on varied assignments from his Hong Kong base, including to the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, Burrows lost his heart to Vietnam.

Tall, rake-thin and with unruly dark hair and thick-framed glasses (he was rejected from the British military because of poor eyesight), Burrows looked part Hollywood matinee idol and part gear nerd (he was often ribbed for forever tinkering with his top-of-the-range cameras). Though a loner, his age, reputation for fearlessness and gentlemanly manner made him a father figure to younger photographers of the war, to whom he would quote from Shakespeare’s Henry V (“We happy few; we band of brothers”).

One of Burrows’ best known photo essays, published in LIFE on April 16, 1965, was entitled ‘One Ride with Yankee Papa 13’ and documented a fatal US mission out of Da Nang. Multiple helicopters were taking part in what was expected to be the routine assignment to airlift republican troops, and Burrows tagged along. When the choppers hit the landing zone, dug-in Viet Cong attacked and “played merry hell,” in Burrows’ words, with “raking crossfire”.

Discovering that another helicopter, Yankee Papa 3, had been downed, Yankee Papa 13 rescued two of its injured American crew. One died while the bullet-riddled aircraft limped home.

Burrows’ pictures, taken before, during and after the firefight, not only convey the panic of the ambush but also tell a human story. The visual narrative begins with fresh-faced, 21-year-old helicopter crew chief Lance Corporal James C. Farley on liberty the day before the mission, goofing around in a Da Nang market. It concludes with Yankee Papa 13 back at base, when exhausted Farley surrenders to his grief, collapsing in tears.

Burrows also pioneered the use of color film in combat photography, giving his work a greater sense of reality than black and white. His most famous color image from Vietnam was taken in 1966, and has come to be called ‘Reaching Out.’ The tableau-like scene reveals wounded Marine Gunnery Sergeant Jeremiah Purdie wading through thick mud and extending his arms towards a fallen comrade on a defoliated, battle-scarred hill just south of the Demilitarized Zone.

In his introduction to the book Larry Burrows: Vietnam, published in 2002, Pulitzer-winning journalist David Halberstam, who reported from the war-torn country for the New York Times in the early ’60s, writes: “Because of … his talent, his courage, and his particular feel for the Vietnamese people, [Burrows] became the signature photographer of that war, a man whose journalism, in the opinion of his colleagues and editors, reached the level of art.”

But while journalists will always hark back on Burrows’ daring and technical brilliance, Tròn remembers his kindness – and his taste for a dashing safari suit.

‘He would make me feel better’

Meeting Burrows, Tròn says, was a “pivotal moment” in her life, and he visited her every month or two. “Even now, I can still see Larry, very clearly,” she says, and her melancholy dissolves. “He would shout ‘Tròn’ and shake my hand. I’m still impressed that he wore this special kind of jacket that reporters wore, with four pockets. He had several of them, I remember.”

Burrows’ daughter, Deborah, was the same age as Tròn, and he reached out to the injured girl and her family, even buying the corrugated-iron sheeting needed to fix the roof of their leaking shack. “He was funny. He always tried to make jokes and cheer me up,” Tròn says. “I was very sad sometimes, and he would make me feel better. He would take me shopping in the city, and when he came to my home he would always bring gifts, like toys or food. Seeing that my family was so poor, he bought materials to rebuild our hut.”

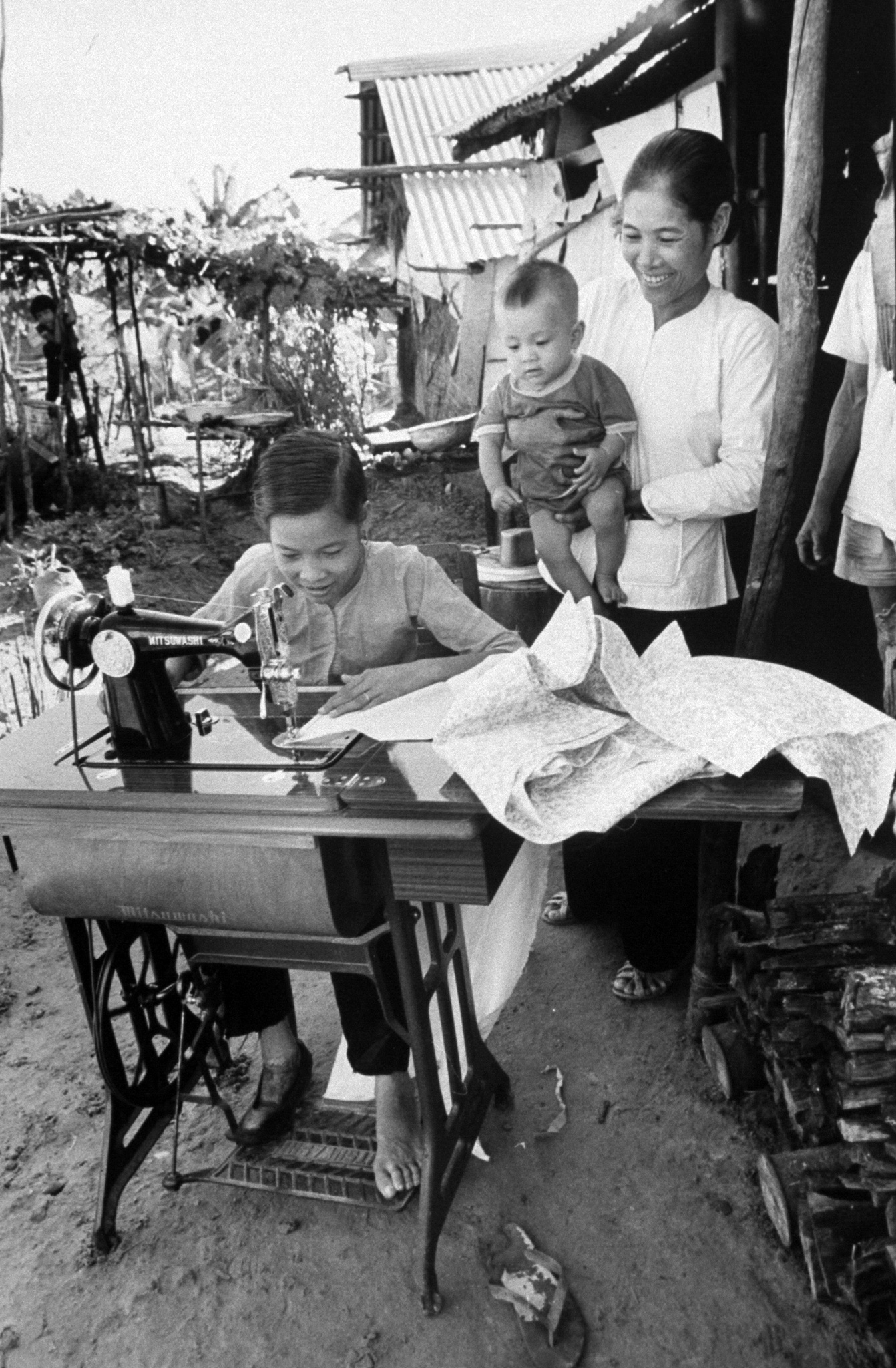

Burrows also recalled moments of fun. “In between picture-taking we played children’s games, some that I knew, some that Tròn had to teach me,” he told his editor. “She wants to be a seamstress so I bought her some cloth. By the time the story was finished we were very close.”

The story of Burrows and Tròn, however, was far from over.

Burrows continued to drop by An Điền in 1969, a year in which “a degree of disillusion,” he wrote in LIFE, had settled over the war-weary South Vietnamese. A nagging unease was also crystallizing in his own work.

The power of Burrows’ photographs of Tròn had pulled at heartstrings in the US, and a two-page follow-up spread appeared in LIFE on December 12, 1969, two years after the loss of her leg. The sequel told of how readers, moved by the girl’s plight, had sent gifts (which Burrows distributed in Tròn’s village); how she had a new baby brother and “had outgrown her original artificial leg and found it difficult to walk without an embarrassing limp.”

Burrows had taken Tròn to be fitted with a more comfortable limb, as well as on shopping trip, which he photographed. “On her recent trip to Saigon, the prospect of buying new shoes excited Tron almost as much as her new leg,” the LIFE text read, continuing, “[…] But in choosing shoes, she might have been any 13-year-old girl. She bought five pairs of practical sandals – and couldn’t resist a pair of pretty white pumps.”

‘Why did you have to die?’

Today, with heat haze rising from the dusty road and only the occasional three-wheel tractor passing by to compete with the cicadas, Tròn’s niece Chi has prepared lunch of rice gruel, chicken cooked with coconut milk, black bean tea, and sliced watermelon and jackfruit. Tròn is pleased that her guest enjoys the simple fare (“I was worried our food would not be acceptable,” she says, smiling shyly), and she searches out the meatiest pieces of chicken with her chopsticks to slip them into my bowl.

Tròn wants me to see her collection of Burrows’ pictures of her, and though confident I’ve seen them all before, her mother, sprightly for her years, leaps onto her bicycle to return in minutes. The pictures – some on photographic paper, others simple laser prints – were given to Tròn by Burrows’ New York-based son, Russell Burrows, who, with his then 16-year-old daughter, Sarah, tracked her down in 2000, when an exhibition called Requiem, of Vietnam War photographs and including his father’s work, opened in Hanoi. (Requiem now has a permanent home at the War Remnants Museum in Ho Chi Minh City.)

Among Tròn’s collection are pictures that never made LIFE’s pages. The most intriguing shows young Tròn outside the family’s hut in An Điền. She sits at a sewing machine, of the old-fashioned type, manually powered by a foot pedal, which she pumps with her prosthetic leg. Her mother, carrying the girl’s new baby brother, stands behind her, smiling proudly.

“Once, Larry asked what I wanted to do when I grew up,” Tròn says. “I said I would like to learn sewing. A month later, he came back with a sewing machine.”

During 1970, Burrows dropped by occasionally when in Vietnam, but persistent malaria meant he spent a proportion of the year working in Europe, away from the tropical heat. He was also concerned about his emotional attachment to the injured Vietnamese child.

“Larry became quite attached to Tròn and she to him, and this worried him constantly,” LIFE’s Saigon Bureau Chief Moser later recalled. “He realized that if she became too dependent on him, her life would be even more difficult when he left her. So he tried to maintain a certain emotional distance from her, acting like a cheerful uncle and trying – not always successfully – to mask the depth of his own feelings.”

Having taken sewing lessons paid for by Burrows, Tròn, now a teenager, used her sewing machine to supplement the family’s income, but by 1972 it was decided that they would move north, to Tây Ninh province, to find work. “Life was so poor where we were,” Tròn says.

Transporting the sewing machine, the family’s only possession of value, would involve a risk. There would be roadblocks along the route, and soldiers might confiscate the expensive machine, suspecting it stolen. Tròn’s mother trekked to Saigon, to LIFE’s office, to find Burrows and obtain a letter confirming ownership.

There she learned that the photographer, at the age of 44, had been killed.

Larry Burrows died alongside fellow photojournalists Henri Huet of the Associated Press (AP), Kent Potter of United Press International and Keisaburo Shimamoto, a freelancer working for Newsweek, when their helicopter was shot down over southern Laos on February 10, 1971. They had been covering Operation Lam Son 719, a massive invasion of the neighboring country by South Vietnamese forces against the Vietnam People’s Army and the Pathet Lao.

Looking back, Tròn says that, as a youngster, she would mischievously play tricks on the Englishman, testing his patience, which she now regrets. Knowing that ice-cold water was not easy to come by, that’s what she would demand whenever Burrows asked if she was thirsty.

“Once he took me in a helicopter from Tân Sơn Nhất airfield, to fly me back from Saigon to my hometown, where there was a big American army base. I said that I only wanted to drink cold water, and he agreed, finding some ice and waiting until it had melted to give to me. Only then did we get the helicopter. He treated me so well and sometimes I was bad.”

The most poignant photograph in Tròn’s collection, which she dwells over more than once, was not actually taken by Burrows. In the picture, Tròn wears an offbeat gift from the newsman: a woolen bobble hat clearly unsuitable for the tropical sun overhead. The photo was shot, possibly by Burrows’ interpreter while holding his camera, when he delivered the sewing machine, the entire village jostling to see.

Two years after Burrows’ death, Tròn’s father fell ill and, with no money for treatment, he also passed away.

Tròn says the photograph, which she has had laminated for its protection, is precious because “it has the two most important men in my life”: her father and Burrows. She runs her fingers over the plastic, brushes a tear from her cheek and whispers to both men, “Why did you have to die?”

‘Talk about grace under pressure’

A U.S. TV news correspondent Edgar H. Needham carried out the last interview with Larry Burrows, at the LIFE man’s office in Hong Kong on Jan. 26, 1971, just 15 days before his death. Writing later in Popular Photography magazine, Needham described him as “an urbane, gracious Londoner with a perpetual twinkle in his eye” and “a phenomenon – one of those people who keep up the average of the human species. He could inspire, but he could not be imitated. His touch with a camera was as sensitive and telling as anyone’s I’d ever seen. And talk about grace under pressure.”

Needham asked Burrows how, having witnessed so much suffering, “he retained his humanity.” Burrows answered at length, recalling ‘One Ride with Yankee Papa 13’: “So when Farley was crying by the open doorway … it’s moments like this when you hesitate and say, ‘Is it my right?’ It’s a thing I’ve said many times: does one have the right to capitalize on the grief of others. The only reason I can give myself is that if one can show to others what these people are going through, in this scene in Vietnam or wherever else in the world, then there’s a reason for doing it.”

Needham also pointed out: “Larry was concerned about being labeled a war photographer. ‘That’s actually a lot of twaddle,’ he almost exploded.”

In the February 19, 1971 issue of LIFE, a week after Burrows’ death, managing editor Ralph Graves delivered a tribute. “He had deep passions, and the deepest was to make people confront the reality of the war, not look away from it,” Graves wrote. “He was more concerned with people than with issues, and he had great sympathy for those who suffered.”

Stories like that of Tròn had cemented Burrows’ reputation as a reflective, empathetic photographer whose work, while having immense journalistic merit, transcended documentary and created a new visual vocabulary for covering war and disaster.

In 1972, LIFE published a retrospective of his work. The book was simply titled, Larry Burrows: Compassionate Photographer.

‘Worse than the old one’

After the death of her father, Tròn used Burrows’ sewing machine to help support her mother and siblings. When the war in Vietnam finally ended on April 30, 1975, with the fall of Saigon and victory for the North, Tròn – now a young woman – trained to become a nurse and later a midwife, working out of the local Suối Đá Commune Health Station.

Chi later followed her into the profession, and today is also a nurse, specializing in providing care to the handicapped.

Throughout her adult life, Tròn has supplemented her income with tailoring. She also fell back on the skill when she stopped nursing, though her eyesight is now beginning to fail. “When I started to feel old, I felt I had to reduce working as a seamstress, but I still need to earn a living, so I opened this store.”

Opening before sunrise and not pulling down the shutters until nine or 10pm – to service rubber harvesters, who work at night – Tròn, who also suffers from diabetes, spent six months in hospital this year being treated for tuberculosis. She puts her ill health down to long working hours.

In the years after the war, Vietnam’s communist government decreed that war amputees should receive funds for new prostheses. “The government paid for a new leg, but it was worse than the old one,” Tròn says. She returned to using the leg made in 1969, which Burrows took her to Saigon to have fitted when she was 13. She still wears that leg today, though weight loss from her recent illness means it no longer fits so well, causing debilitating pain when she walks.

Tròn lifts the leg of her pants to reveal that the wooden leg – almost half a century old – is cracked and held together with a strip of bandage tightly wrapped just below the knee.

‘It’s the career Larry gave me’

The remoteness of the jungle crash site in Laos, as well as political restrictions, made recovery of the journalists’ remains impossible for decades. In 1998, veteran AP correspondent Richard Pyle and his photographer colleague Horst Faas, who had been friends of Burrows in Vietnam, mounted a campaign to retrieve their bodies.

Working with Pentagon forensic experts, they discovered fragments of cameras and lenses, rolls of 35mm film, rubber boot soles and other debris. The mangled metal body of a Leica camera and a watchband are believed to have belonged to Burrows. The remains of the four journalists, as well as those of a South Vietnamese military photographer also aboard the helicopter, and its Vietnamese crew, were honored and interred at the Newseum in Washington, D.C. in 2008.

“Burrows was of that breed of photographers who were acutely conscious of the human misery they portrayed,” Pyle and Faas wrote in their resulting book, Lost Over Laos, adding that time spent with Tròn had affected him deeply.

Tròn was also profoundly changed by their relationship, and she remains so. She says she often thinks of Burrows, who gave her not only kindness, but a practical means of survival.

And Tròn continues to sew.

“People say, ‘You are old now, you don’t need to do this any more, you should retire from tailoring,’” she says, “but I still feel passionate about it because it’s the career that Larry gave me. I want to do it until my eyes can see no longer.”

The sewing machine at the entrance to Tròn’s store today is powered by electricity rather than a foot pedal. The machine that Burrows gave her, having been repaired many times, finally gave up the ghost less than 10 years ago. “I used it until it had too many problems,” Tròn says. “The mechanic said it was worn out.”

Rusted and idle now, the sewing machine is stored in a cabinet in Tròn’s home. She keeps it in memory of her childhood friend.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com