Americans will mark Women’s Equality Day on Saturday in commemoration of the day in 1920 when the 19th Amendment guaranteed women the right to vote. But the history of women in American politics predates that anniversary by decades. Long before suffrage was extended to women nationwide with that Constitutional amendment, women were running for office — and winning — in some states with more inclusive qualifications for voting and holding office.

In fact, at least 3,586 women campaigned for elected positions in the half-century before 1920, according to Her Hat Was in the Ring, a database created by scholars Wendy E. Chmielewski, Jill Norgren and Kristen Gwinn-Becker. (The archive is a work in progress, and that number represents the women they’ve counted for sure so far; the trio estimate that they’ll ultimately find that more than 5,500 women ran in about 7,000 campaigns.)

Much has been written about Jeannette Rankin, the first-ever woman elected to a national office in 1916, who represented Montana in the U.S. House of Representatives, and Victoria Woodhull, the first woman to run for president in 1872.

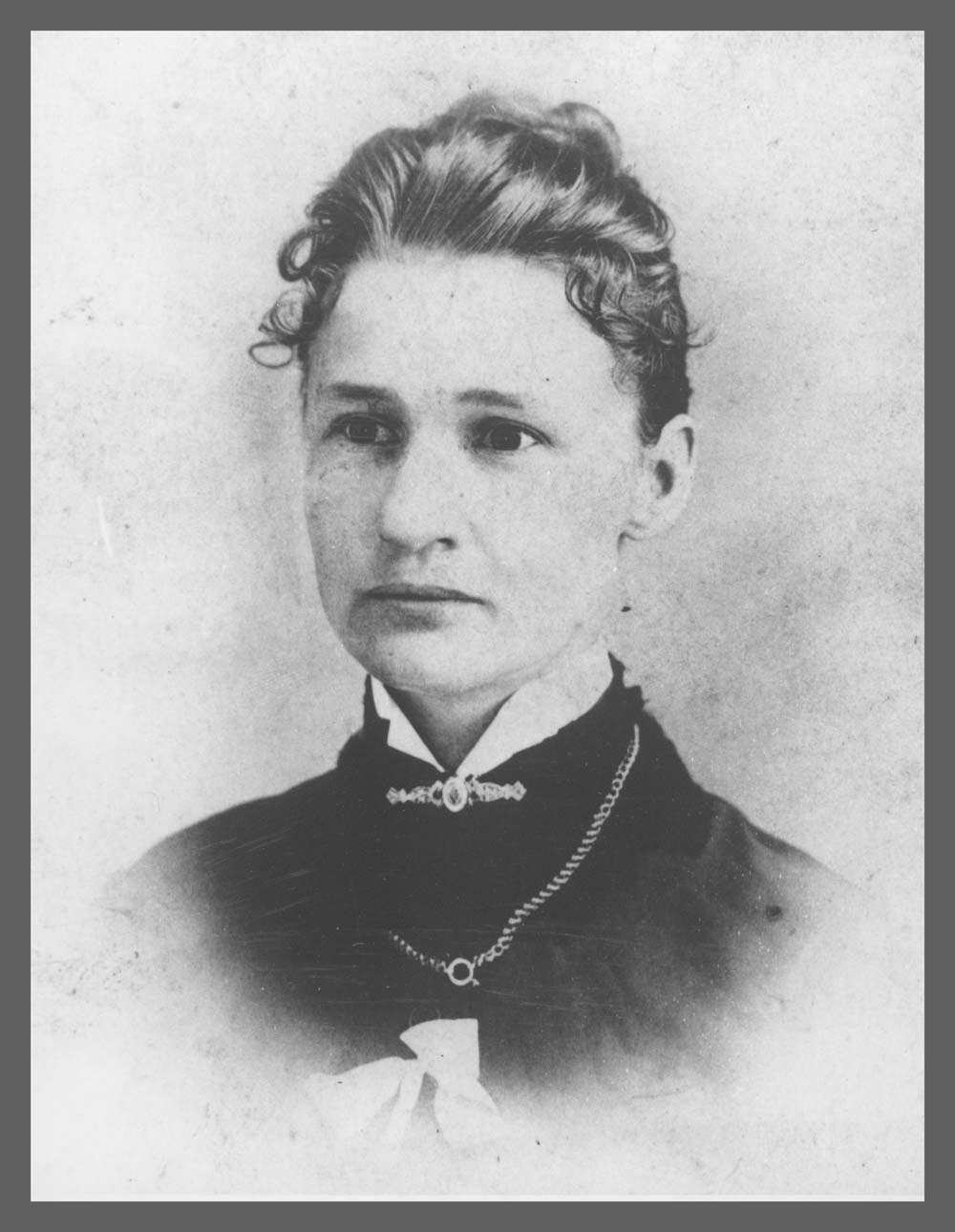

But the database sheds light on some of the lesser-known names who claimed firsts during this period. Susanna Salter became mayor of Argonia, Kans., in 1887, and the country’s first female mayor. In Utah, Dr. Martha Hughes Cannon — in addition to boasting the achievement of finishing medical school at 23 — became the first female state senator to be elected in the U.S. in 1896. And when Olive Rose was elected Register of Deeds by Lincoln County in Maine in 1853, she became not only the first woman elected in the state, but the scholars believe she may have also been the first woman elected in the United States. In one town, Warren, she got 73 votes, while her opponent received only four. Her listing in the database includes a rather prescient announcement of her feat in a local newspaper article:

“Men may laugh and jeer and fume, as much as they please about this matter of ‘woman’s rights;’ they cannot escape the issue. As sure as the indomitable barons of England wrung Magna Carta from King John at Runnymede, so will the women of the 19th century extort from the ‘lords of creation,’ (who have held them in servile dependency from the beginning of the world) something like an equal share of political and social rights. Whether the doctrine of ‘woman’s rights is in the judgment of the present generation consonant with the ‘eternal fitness of things’ or not, it is nevertheless designed to gain ground, and ultimately to prevail.”

However, the vast majority of these electoral successes were achieved further West than Maine. In Kansas alone, more than 750 women were elected to all kinds of offices before 1912, according to Chmielewski. Most of the states and territories that pioneered women’s suffrage were newer to the Union, eager to attract families to move West and relatively open to new ideas. There, women could often get a foot in the door on school or sanitation boards, which were seen as extensions of women’s domestic work.

“Many states agreed that elected offices not mentioned in the original state constitutions — like superintendent of schools, a position that only started coming about in the 1860s and 1870s — had a lot more freedom of who could be elected to it, including women,” says Chmielewski. And in some places, adds Norgren, “the attitude of men is [that] other men have done a bad job and women are known for being clean and honest.”

Though it would take decades for women across the U.S. to get the right to vote — and decades more for it to be guaranteed for women of color — those early candidates and voters played a key role. As states gradually began granting women’s suffrage, that meant women were voting in presidential elections, and party strategists started to take notice. “Political parties began to recognize women as an important part of the electorate,” says Sally McMillen, author of Seneca Falls and the Origins of the Woman’s Rights Movement, “and realized that they needed them.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com