For decades, airport security officials depended on metal detectors to screen travelers for concealed weapons. The technology was safe and simple but had one glaring flaw: it could not detect non-metal threats, including plastic explosives. In 2009, the infamous underwear bomber almost exploited that flaw to devastating effect.

In the aftermath of that near-tragedy, the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) moved quickly to update its screening procedures and technologies. By 2010, it had implemented two new types of full-body scanners.

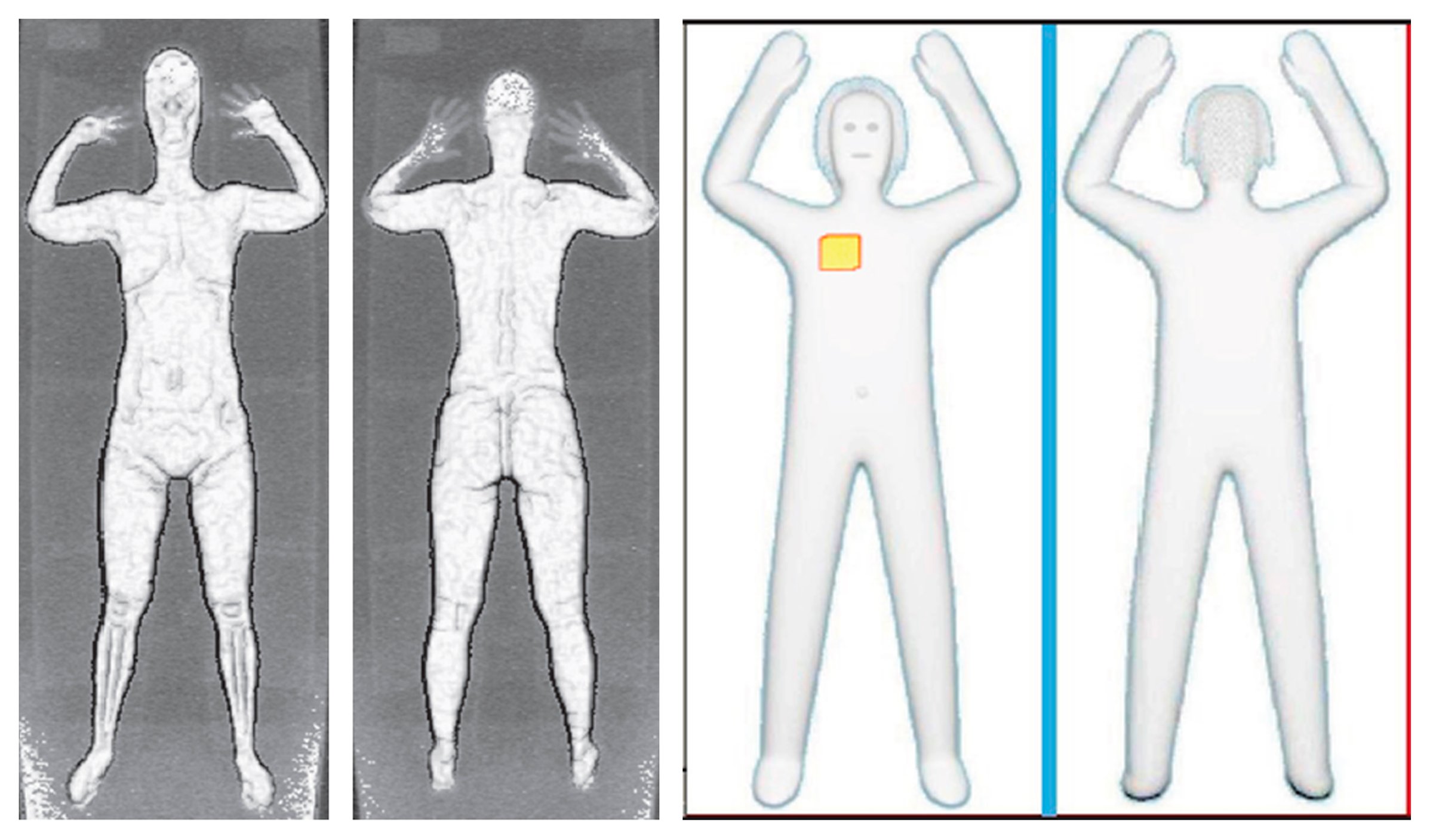

One of these, called a millimeter-wave scanner, uses radio waves to search for hidden weapons or devices. These are the full-body scanners you’ll encounter at U.S. airports today—the ones you stand in with your feet apart and your hands above your head—and experts agree they shouldn’t worry you.

The second (and far more controversial) of the two is called a “backscatter” X-ray scanner. You’ll remember this as the machine that produced revealing full-body images of passengers that many found unnecessarily intrusive.

Apart from the privacy questions posed by the use of the backscatter technology, some experts also had concerns that those scanners exposed travelers to potentially dangerous amounts of radiation. “We determined that the exposure from those machines was about 10% of what you’d get during a chest X-ray, which is significant,” says John Sedat, a professor of biophysics at the University of California, San Francisco.

“There was probably some very small cancer risks associated with those X-ray machines,” says David Brenner, a professor of radiation biophysics at Columbia University Medical Center. “We know there are biological mechanisms by which X-ray exposure can cause cancer…it seemed likely that those backscatter scanners would carry some small risks.”

European authorities almost immediately banned the use of the backscatter X-ray machines, and the TSA followed suit in 2013—though the agency never formally acknowledged that it was dumping the scanners due to health concerns. (It also hasn’t ruled out bringing them back.)

But with the machines used today, there’s no widespread health reason to opt out.

“Scientists can never say that something is 100% safe, but I would say there’s no plausible evidence by which millimeter waves could damage DNA,” Brenner says. “If the risks are there, they’re extremely small.”

MORE: Here’s How To Take A Perfect Vacation

Andrew Maidment, an associate professor of radiology at the University of Pennsylvania Health System, agrees, and says the current scanners are “not a concern.”

Maidment has published dozens of studies on radiation exposures and human health, and he’s responsible for ensuring all of Penn Medicine’s medical equipment is safe for patients. He explains that microwave-emitting devices—from the heating appliance in your kitchen to the smartphone in your pocket—are believed to cause health harms only when they’re powerful enough to cause molecular changes. The radiation emitted by airport millimeter wave scanners don’t come anywhere close to this level.

“I was on a panel that examined exposure [of these types of microwaves] to pregnant and potentially pregnant patients and neonates, and I’m convinced they are safe,” he says. “I don’t worry about them for myself or my wife or my children.”

MORE: This 10-Second Quiz Can Tell You if You Should Get Screened for Lung Cancer

While some experts have raised theoretical concerns about less-powerful forms of microwave radiation, especially the types emitted by mobile devices and technologies, Brenner says what you encounter passing through an airport scanner is such a low dose—and something you experience so infrequently, even if you’re a regular flyer—that you don’t have much to worry about.

“It’s beyond my imagination to theorize a significant cancer risk from use of these millimeter wave scanners,” he says.

In fact, the only criticism any of these experts had about airport scanners had nothing to do with radiation exposure or cancer. “We had something fast and cheap and very accurate in the old metal detectors, and they beeped loudly when they found something,” Maidment says. “But now we’ve replaced them with something that relies on a person staring at a screen to find things, and so we’ve brought human error and foibles into the equation.”

He points out research that concludes it’s very possible for someone to dupe the new scanners and sneak camouflaged guns or explosives past their defenses. “This is my personal opinion, but these new machines”—which cost more than $150,000, compared to just $30,000 for a metal detector—“are too expensive and too inaccurate.”

But how best to keep passengers safe from airport threats is another story. As far as cancer concerns go, you can feel safe stepping inside airport scanners.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Contact us at letters@time.com