“It’s beautiful. Should I take a picture for my Instagram?” Aubrey Plaza stands up to snap an iPhone photo of the avocado toast that’s just arrived at our table. She carefully moves our water glasses to declutter the shot, which she says she’ll post the week her new movie, Ingrid Goes West, hits theaters. In the film, her character also uploads a perfect portrait of the overpriced green grub to her Instagram, with the aim of impressing a social-media influencer she wants to befriend. Now Plaza shakes her head and laughs, saying, “This is stupid.” She’s humoring me, because I’ve asked her to meet me–in honor of the film’s theme of millennial social-media obsession–at lower Manhattan’s Café Gitane, the birthplace of the food trend that’s become an Instagram cliche.

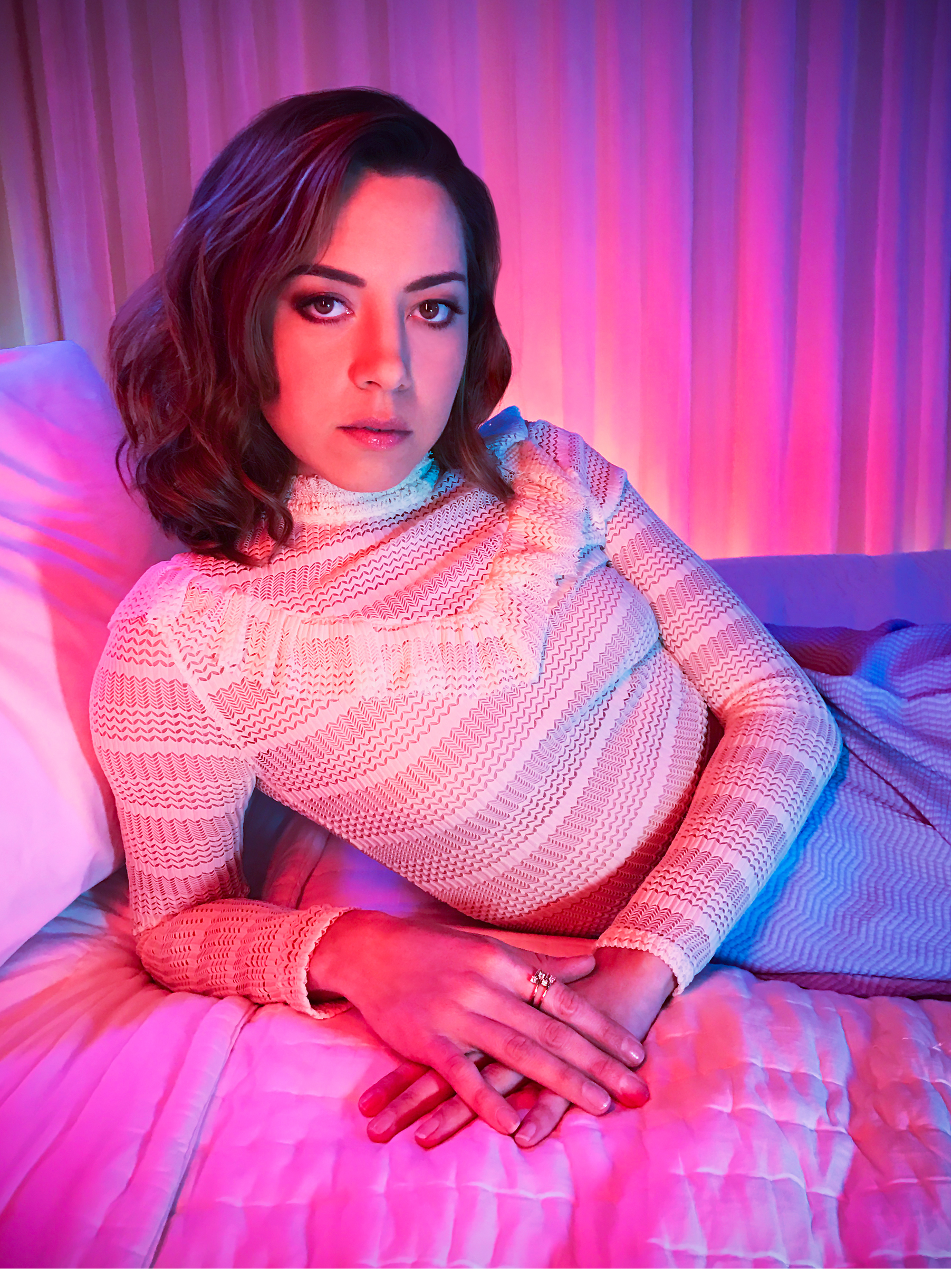

Plaza, 33, hates social media. But she’s willing to ‘gram and tweet as much as necessary to get people to see the film, which she also co-produced. Directed and co-written by newcomer Matt Spicer, Ingrid follows a lonely young woman who, after the death of her mother, uses her inheritance to move across the country, make herself over and befriend an Insta-celebrity (Elizabeth Olsen) who’s famous because she eats the right toast and wears the right floppy hats. Plaza is brilliant, playing Ingrid with a teetering balance of fragility and derangement.

Ingrid is also a window into a phenomenon with which Plaza is familiar: the gulf between who people are and who others perceive them to be. It’s been two years since she said goodbye to April Ludgate, the enthusiastically apathetic municipal cog she played for seven seasons on NBC’s Parks and Recreation. But many of Plaza’s fans hold fast to the notion that Aubrey is April and April is Aubrey. Plaza cops to being complicit in the confusion. “I have a whole cycle of feeding this persona that has been projected onto me,” she says. “My reaction to it as a people pleaser is to give that back, which isn’t always authentic to who I really am.”

Plaza has wanted to be an actor since her first acting workshop around the age of 10. At her all-girls Catholic school in Wilmington, Del., she was both a type-A student running for president of every student organization and a class clown. Like April, she loved Halloween, but not for its celebration of the macabre. She loved that it allowed her to dress up in costumes and play characters–in other words, to act.

When she wasn’t in school, her life revolved around movies: making them, watching them and checking them out to customers at a video-rental shop. She worked there alongside her aunt, who introduced her to independent films like Christopher Guest’s Waiting for Guffman and John Waters’ Serial Mom. She also fondly remembers watching Jurassic Park and anything that ended with a kiss between Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan. “It wasn’t like I was watching Fellini,” she says.

Her film education continued when she went to New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts and honed her comedy skills at the Upright Citizens Brigade, co-founded by future Parks co-star Amy Poehler. She hoped to have a career like Adam Sandler’s: join Saturday Night Live, make her own movies and take on the occasional dramatic role. But before she got the chance to emulate Sandler, she was cast opposite him in Judd Apatow’s Funny People, after which she began her gig on Parks.

Since then, Plaza has proved that she can do much more than roll her chestnut eyes. In The To Do List, her virgin valedictorian brings a Poindexter-tinged mania to completing a Trapper Keeper full of sexual ventures before college. In the raunch-fest Mike and Dave Need Wedding Dates, she played a crass manipulator who smokes weed out of apples and eats leering bros for breakfast (metaphorically speaking–the zombie she played in Life After Beth literally does eat dudes).

If there’s a common denominator, it’s a smidge of sociopathy–which makes Plaza perfect to play Ingrid. The character’s behavior in the film’s opening scene–crashing a wedding and pepper-spraying the hashtag-happy bride–could easily be classified as crazy. But Plaza grappled with whether or not Ingrid was actually mentally ill. “Borderline personality kept coming up when I was trying to understand what kind of person would do something like this,” she says. “I did explore that. But I never wanted to make it completely about that.” To Plaza, the movie shows what happens when a person who’s ill-equipped to handle a barrage of envy-inducing status updates gets her hands on a phone and a 4G data plan.

Ingrid upends her entire life, from zit cream to zip code, to bask in the sun-soaked glory of a total stranger, one who–it’s hardly surprising–turns out not to be the picture of bliss she cultivates. “I wanted Ingrid to be the personification of that unhealthy urge to spiral, looking at other people’s lives and wanting a connection,” says Plaza. So the actor, who says spending hours staring at her phone “goes against every instinct in my body,” did just that. “When the camera was rolling, when it wasn’t, I was on Instagram, letting myself go down those holes. It’s really depressing to be sitting in one position, not interacting with the world, looking at other people’s photos and wanting what they have.”

“I want to be Catwoman more than anything,” Plaza says, eyes widening, when I ask her what she wants to do next. “I made myself Catwoman in Ingrid,”–she’s referring to some bedroom role-playing with co-star O’Shea Jackson Jr., who plays Ingrid’s Batman-infatuated landlord–“because I was like, This might be as close as I get.”

I ask what she’d be doing if she weren’t in show business, and she says she’d be an agent. “I’m always telling other people what they should do in their careers,” she explains. But then she says that’s a cheap response, since agents are acting adjacents, and settles on an alternative: “Maybe I would run a haunted bed-and-breakfast somewhere and be a weird hotel woman.”

It sounds like she’s feeding me an answer that witchy April would have sanctioned, and I ask if I’ve caught her in the people-pleasing feedback loop she explained earlier. “No, I really want to do that,” she says. “But I wouldn’t be mean about it.”

It’s the association with April’s meanness that seems to bother her the most. The sarcasm she owns–when our avocado toast arrives, she begins sneezing (for real) and deadpans that she is allergic (not for real, though it took me a moment to suss that out) before taking a big bite. But the hostility she objects to. She tells the story of a recent interview, when a reporter began, “So, you’re really mean,” which prompted her to defend herself in a way that she feared came off as, well, mean. “I don’t know what you’re going to write,” she tells me now. “I don’t trust anyone. I mean, you seem nice, but …” she trails off. “I’m always like, Don’t say anything stupid.”

I think about what she would want me to write, and it’s this: Aubrey Plaza would like you to go to the theater and see the movie she poured her heart into. And not out of some desperate need for affirmation. More and more we’re watching films–particularly those that don’t seem to warrant the surround-sound of a cinema–from our couches. “When we used to go see movies in theaters growing up, there was something about just the image being really big that sticks in your mind. It has a lasting impression on your psyche,” she says wistfully. “But I don’t know what’s going to happen. I have faith, because I think people need to gather and experience things as a group. They need that connection.” A connection deeper than the dopamine release we get when someone likes our latest Instagram post.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com