Considering the source, it was a startling claim. A longtime lieutenant of TIME and LIFE founder Henry Luce, journalist Richard Clurman found himself chatting one day in the late 1960s with Leonard Bernstein, the legendary composer and conductor of the New York Philharmonic. “Elvis Presley,” Bernstein said, “is the greatest cultural force in the 20th century.” Taken aback, Clurman, who recounted the exchange to the writer David Halberstam, offered an alternative.

“What about Picasso?” Clurman ventured.

“No, it’s Elvis,” Bernstein insisted. “He introduced the beat to everything and he changed everything–music, language, clothes, it’s a whole new social revolution–the ’60s come from it.”

As does so much else. Forty years after Presley’s August 1977 death in an upstairs bathroom at Graceland, his Memphis mansion, the revolution Bernstein identified unfolds still. With an estimated 1 billion units sold and counting, Presley is thought to be the most commercially successful solo musical artist of all time. Last year, the Recording Industry Association of America certified the Essential Elvis record platinum, and in 2016, Presley was, according to Forbes, the fourth top-earning dead celebrity in America, trailing only Michael Jackson (who, in an only-in-America twist, was once married to Presley’s daughter), cartoonist Charles Schulz and golfer Arnold Palmer. Legions of fans–many of whom were born after the King was found lifeless, his body wracked by opioids–treat him as a Christ-like figure, a man born on the fringes who attracted a great following and who some still believe is not dead. The site this month of a panel discussion with Priscilla Presley, a sold-out “Ultimate Elvis Tribute Artist Contest Showcase” and a vigil on the anniversary of his death, Graceland is among the most-visited private homes in the nation along with the White House, which is fitting, since the Presley phenomenon has particular resonance in the age of Hillbilly Elegy. “What he did was earthshaking,” says Tim McGraw, the country-music superstar who counts Presley as a huge influence. “He changed not only the music that we make but social norms and the way we looked at each other.”

He also changed how we are able to look at, and experience, him in the 21st century. Ted Harrison, a British writer and broadcaster who’s done landmark work on the Presley phenomenon, notes that investors in the “Elvis brand,” thanks to the Presley family, have had unusual artistic and commercial freedom. Next up: a hologram Elvis that can carry an entire concert. “Elvis,” Harrison says, “will continue to grow.” Fans, it turns out, need never have a lonesome night.

The Presley legend has proved durable and intriguing not least because it mirrors much of American culture in the artist’s lifetime and beyond. His fantastic rise and long, sad slide into an overweight, gun-toting, prescription-drug-abusing conspiracy theorist about communism and the counterculture (he hated the Beatles, once telling President Nixon that the British band threatened American values) tap into fundamental questions about race, mass culture, sexuality and working-class anxiety in a postwar America. A poor boy made good in the prosperous 1950s, Presley experienced tension and feared disorder in the 1960s before breaking down totally in the hectic 1970s. In his music and movies, in his private worlds at Graceland and in Las Vegas, Presley was a forerunner of the reality-TV era in which celebrities play an outsize role in the imaginative lives of their fans. Before Diana, before Michael, before Kim, before Trump, there was Elvis.

I. RISING SUN

Presley was born in Tupelo, Miss., in 1935 in the hilly upcountry region of the state that the writer Julia Reed has described as the Balkans of the South. (The other two distinct Mississippi worlds are the Delta and the Gulf Coast.) His father struggled to eke out a living, working different jobs and signing up for FDR’s Works Progress Administration after doing time at Mississippi’s Parchman prison for forging a check. His mother was devoted to her son, all the more so because Presley had had a twin brother who was stillborn. Presley grew up as a member of the Assembly of God, a denomination that emphasized personal religious experiences. Music and singing were essential means of creating ecstatic moments of transcendence: a vibrant, emotional, very public form of faith. The individual was the vessel of the Holy Spirit–a performer, if only for the congregation.

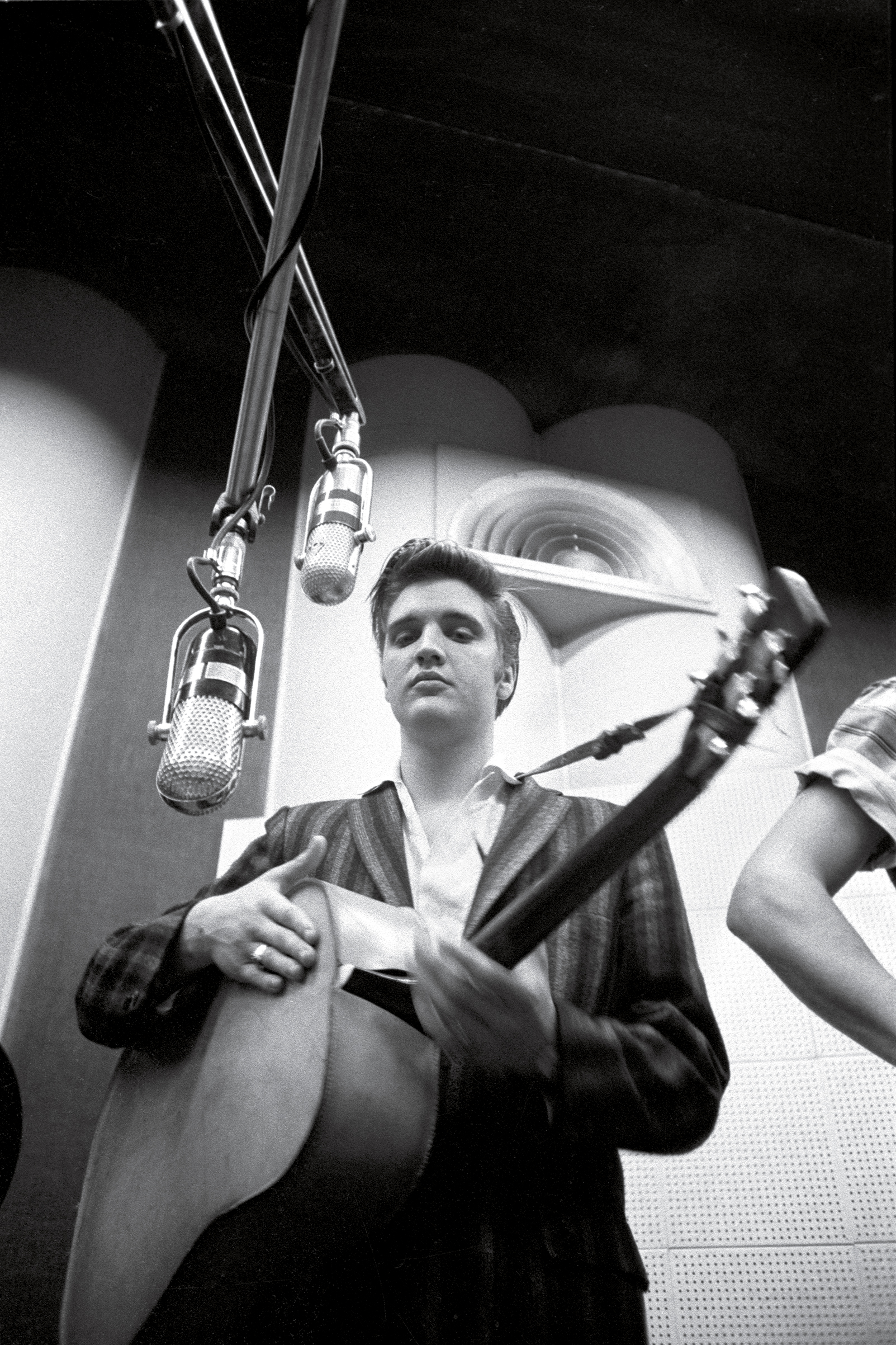

Eventually the family moved to Memphis, which was perfect for Presley. A longtime cotton hub, the city, like Presley himself, sat between the blues-soaked Delta and the virtually all-white country-and-western music world of Nashville. In the summer of 1954, after a brief, not-quite-successful visit the year before, Presley cut a record with the producer Sam Phillips, who ran Sun Records on Union Avenue.

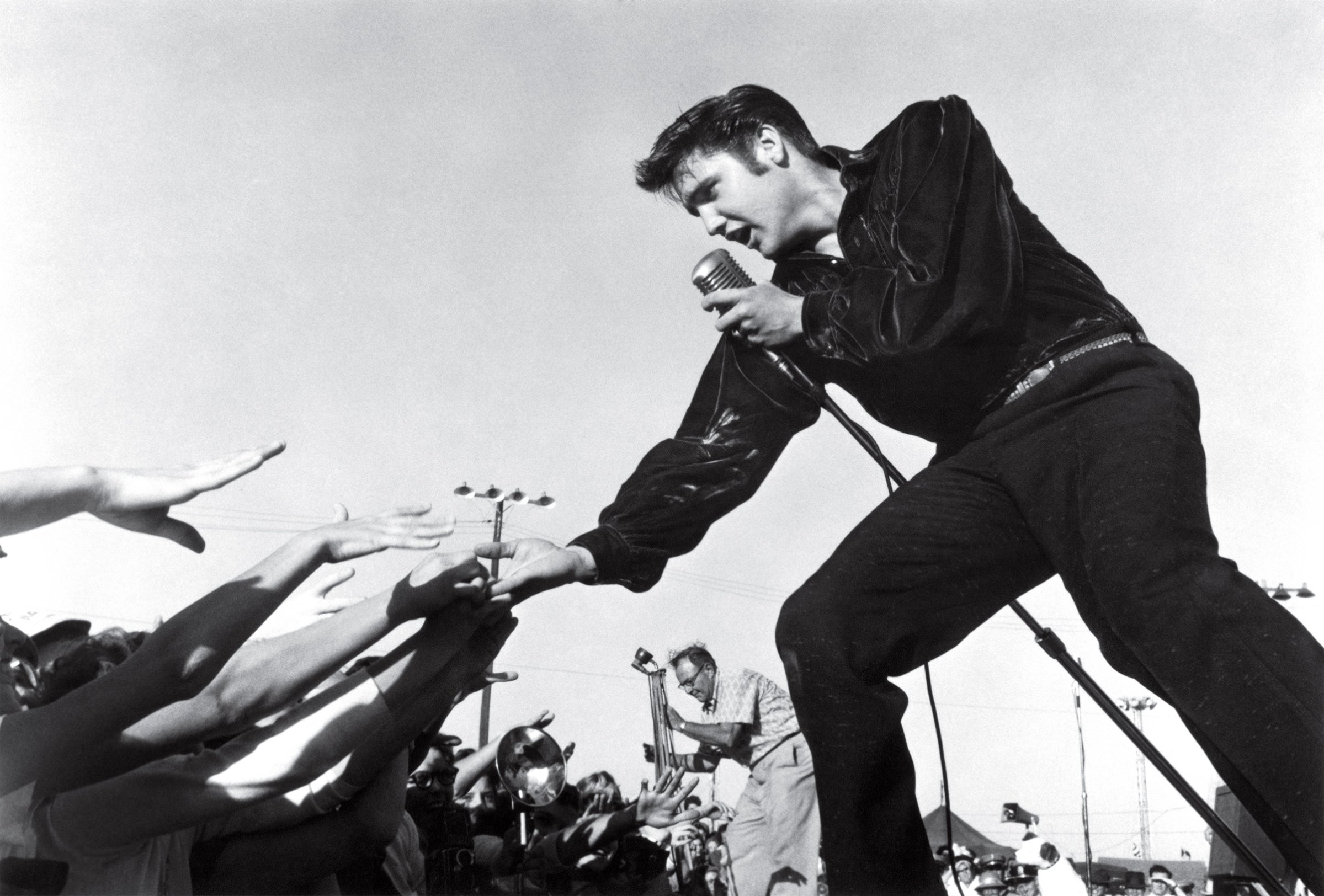

A few weeks later, at an open-air performance at Overton Park Shell in Memphis, Presley played the two songs from that recording. As Joel Williamson, a scholar of Southern history, observed, Presley took “That’s All Right” (written by an African-American blues musician, Arthur Crudup) and “Blue Moon of Kentucky” (written by a white bluegrass man, Bill Monroe) and made them his own. “Elvis, using his God-given rich and versatile voice, perfected by practice, gave [the songs] a different turn,” Williamson wrote. “Just as ‘That’s All Right’ was not black anymore, ‘Blue Moon’ was no longer hillbilly; it was joyous, country-come-to-town and damn glad to be there.” The audience, led by ecstatic young women, went wild. “I was scared stiff,” Presley recalled. “Everyone was hollering, and I didn’t know what they were hollering at.”

That much, at least, should have been clear: they were hollering at him, transported by his electric physicality and extraordinary voice, which ranged comfortably from baritone to tenor and above. He did not simply sing; he became the music, as though possessed by a spirit of joy and release back at the Assembly of God. It was sexual, yes, and thus disturbing to the more placid and puritanical observers, but it was inescapably religious too, in the sense that religion evokes realities ordinarily hidden from the human eye. Here, on a covered stage in a park in western Tennessee, a white man was drawing on the deep tradition of African-American blues. In the popular mind, a fresh genre–a different epoch–was emerging. “Before Elvis,” John Lennon is said to have remarked, “there was nothing.”

That was not strictly true. Presley was a vehicle–cultural critics would say he was basically a mimic, or even a thief–of the black musical and spiritual experiences of his native Mississippi. Phillips, the maestro of Sun Records who recorded artists such as B.B. King and Ike Turner in a still-segregated South, understood the underlying realities of Jim Crow America. Chuck Berry and Little Richard would be early breakout stars across the color line, but Phillips believed that would not be enough to integrate the cultural and commercial markets. “I knew that for black music to come to its rightful place in this country, we had to have some white singers come over and do black music–not copy it, not change, not sweeten it. Just do it,” he said. With Presley’s emergence (as well as Bill Haley’s and Jerry Lee Lewis’, among others), Phillips’ prophecy came true, but not without resentment from the architects of the tradition Presley was drawing on. “I was making everybody rich, and I was poor,” said Crudup, who originally recorded “That’s All Right.” “I was born poor, I live poor, and I’m going to die poor.”

In the white mainstream, Presley’s story was quintessentially American–a striver rising to riches from largely impoverished obscurity (his family lived in a federal housing project in Memphis after moving to Tennessee) on the strength of his talent, not on the circumstances of his birth. “I don’t know what it is,” Presley told the Saturday Evening Post in 1956. “I just fell into it, really. My daddy and I were laughing about it the other day. He looked at me and said, ‘What happened, E? The last thing I can remember is I was working in a can factory and you were drivin’ a truck’ … It just caught us up.”

II. THE SURGE

Presley emerged at the moment the machinery of post–World War II mass culture began to hum. The world was on the move; old barriers were under siege; new possibilities were opening up. It was the age of the GI Bill and Brown v. Board of Education, suburbs and television, interstate highways and fast food. Material prosperity in Eisenhower’s America was startling. Families whose forebears had struggled on the fringes of farming and of debilitating manufacturing work suddenly had more money (and more things, ranging from TVs to washing machines) than they could have imagined two decades before, in the depths of an economic crash that seemed to go on forever. When John Maynard Keynes was asked whether there had ever been anything like the Great Depression, he had replied, “Yes. It was called the Dark Ages, and it lasted 400 years.” One unexpected benefit from the postwar boom was rising disposable income. Teenagers were able to consume the product that Presley was offering.

A key element of that product: overt sexuality. This wasn’t Bing Crosby up there; it wasn’t even Frank Sinatra, who sang so intimately and so searchingly. Presley was something much different. Beyond his husky, unique voice, the artist, with his gyrating hips and hooded eyes, seemed to embody desire more than any other popular male performer of his time. One report in Presley’s vast FBI file–created and maintained under the decades-long reign of J. Edgar Hoover–described a La Crosse, Wis., show in lurid terms. It was, the writer said, “the filthiest and most harmful production that ever came to La Crosse for exhibition to teenagers”; Presley projected nothing less than “sexual gratification on stage.”

A white man singing traditionally black music; a young performer with sexual heat; a Southern kid going national: little wonder Presley struck so many as so refreshing in the mid-1950s. “Hearing him for the first time,” said Bob Dylan, “was like busting out of jail.” Many women, particularly young women, had a similar reaction.

III. AT THE ZENITH

It’s an oft-told story: on Sept. 9, 1956, Presley made his first appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show, the Sunday-night cultural juggernaut, producing an 82.6% TV rating. His second turn on the show was also a blockbuster, and by the time Presley sang for Sullivan on a third occasion–when CBS directed the cameras to show Presley only from the waist up–the buttoned-down host had been won over. “I wanted to say to Elvis Presley and the country,” Sullivan intoned, “that this is a real decent, fine boy.”

Religiosity also helped Presley win broader acceptance. As with so many Southern men, he could seem equally at home in church as he did in juke joints. Americans are familiar with the type: we had one for President for two terms at the close of the 20th century. Bill Clinton’s mother Virginia worshipped Presley, and Memphis was to Hot Springs as John Winthrop’s “city upon a hill” was to sentimental patriots. Clinton’s own longtime affection for the King isn’t surprising. Presley was a model compartmentalizer, creating music that celebrated a freer attitude toward sex while simultaneously releasing gospel tracks. As has often been remarked of charismatic figures such as the fictional James Bond and the real-life Presley, women wanted to be with him; men just wanted to be him.

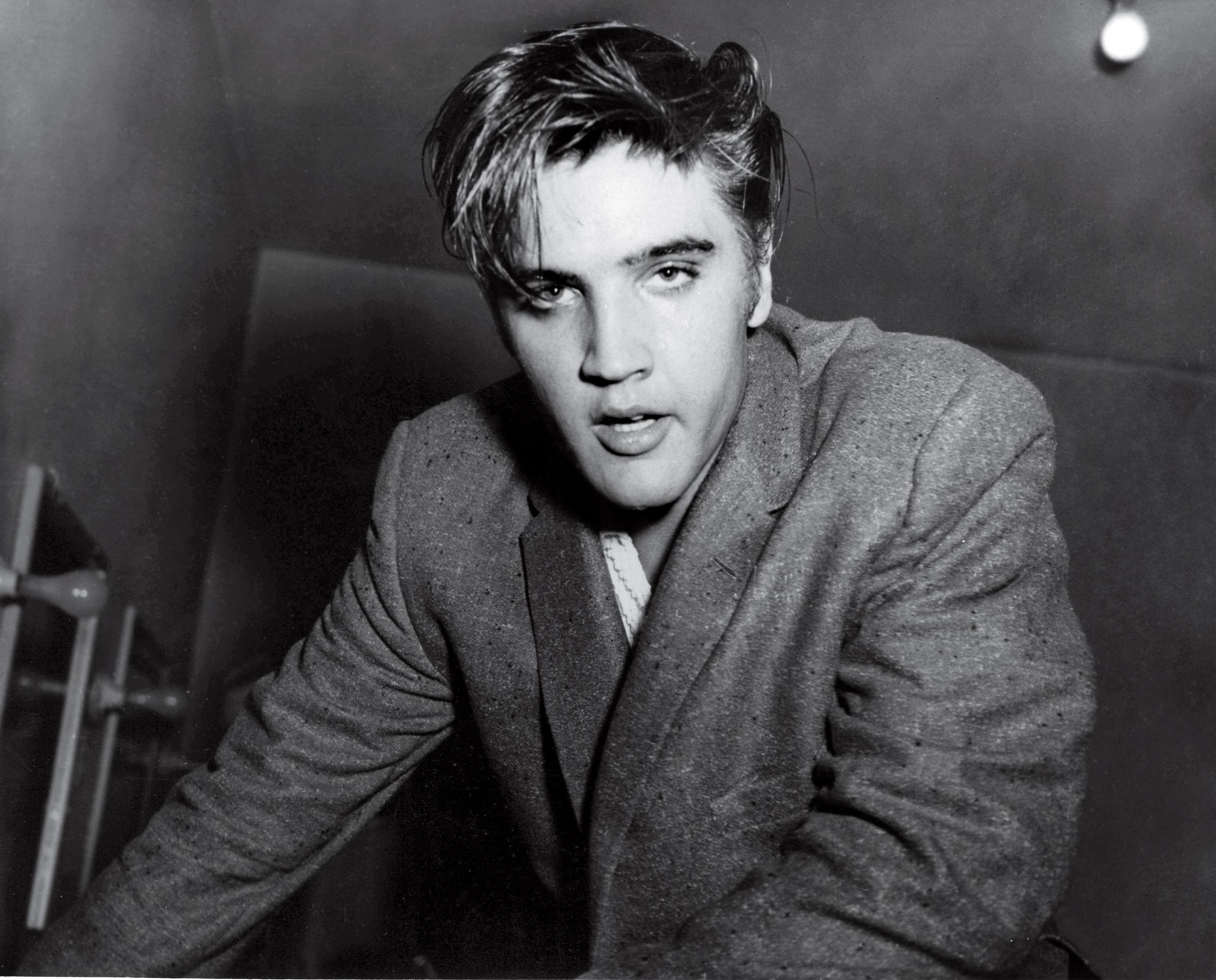

Presley took that potent formula for success to Hollywood as soon as he could. Upon seeing Presley perform, Jackie Gleason, who in addition to acting and comedy produced a national Saturday-night broadcast called Stage Show, remarked, “He’s a guitar-playing Marlon Brando.” Presley would never come close to Brando as an actor, but Gleason was onto something: Presley’s appeal was like Brando’s or James Dean’s, that of a rebel straining against the strictures of the middle-class world that bought his records–Presley had a string of hits beginning in the mid-’50s–and went to his movies. As David Halberstam put it in his book on the era, The Fifties, “a great deal” of Presley’s force came from “the look: sultry, alienated, a little misunderstood, the rebel who wanted to rebel without ever leaving home.” Presley, Halberstam wrote, “was perfect because he was the safe rebel.”

Presley’s films, often formulaic, were safe to the point of stolid. He made four from 1956 to 1958: Love Me Tender, Loving You, Jailhouse Rock and King Creole. Presley sang through most of his roles, though much of his movie work brings to mind President Reagan’s observation about the studio mill. “They didn’t want them good,” Reagan said, “they wanted them Thursday.” Still, Presley adored being on the big screen, and his musical career, so meteoric in the ’50s, stalled somewhat in the ’60s.

IV. COMEBACK AND DESCENT

In 1968, everything in Presley’s universe changed. In the wider world, it was the year of Tet; President Johnson’s sudden withdrawal from the presidential race; the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy; and, in November, the election of Richard Nixon. For Elvis, ’68 was the year of his “comeback” special, which aired on NBC. To watch the show is to see a master performer at the top of his game. Lithe, beautifully costumed in black leather and as handsome as ever, Presley sings, plays and dances in the round, surrounded by an audience that’s more sedate yet just as rapt as the ecstatic crowds of the ’50s.

Not long afterward the last chapter began. He had married Priscilla Beaulieu in 1967 and divorced her six years later; they had one daughter, Lisa Marie, born in 1968. Presley gained weight and found himself taking more and more prescription uppers and downers. He created an insular life populated by a swirl of women, who were often quite young, and by “the guys,” his Memphis mafia of musicians, bodyguards and hangers-on who catered to the whims of the King. It was the oldest story in the annals of celebrity: a star becomes ever more reclusive and eccentric as his fame grows beyond measure. Lord Acton’s dictum about absolute power corrupting absolutely has a show-business analogue: absolute notoriety all too often tends to corrupt absolutely too.

Presley’s descent was marked by an obsession with collecting police badges and firearms; it was as if he were seeking the emblems and means of control as he himself grew more erratic. In 1970, en route to Washington, Presley wrote Nixon a letter on American Airlines notepaper claiming that he had new insights into the youth unrest across the country as well as communist “brainwashing” techniques. Would the President be interested in Presley’s becoming a secret agent of the federal government? The request led to an impromptu meeting in the Oval Office, where a puzzled Nixon listened to Presley’s ramblings about the moral degeneration of the country.

Although the session itself was bizarre–Presley had basically presented himself at the White House without an appointment, only to be admitted to see Nixon–the content of the conversation was perhaps not that different from what many white Americans of Presley’s background would have said to the President at the time. Presley came from the white working class, a demographic that had helped elect Nixon, who in a speech a year earlier had referred to his base as “the great silent majority”–the ones who didn’t protest, who didn’t grow their hair long, who didn’t burn their draft cards or run the country down. In a concert in the 1970s, Presley included a bit of “Dixie Land” and climaxed with a stirring section of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” as well as gospel numbers. And so, like the nation in the years of Vietnam and Watergate, he was awash in both patriotism and self-indulgence, clinging sentimentally to an older, warmer vision of America even as he fed his own appetites for opioids and fried peanut butter and banana sandwiches. Presley’s own contradictions were similar to the country’s as it hurtled through a difficult and self-involved decade.

He would not, of course, see the ’70s through. In the middle of August 1977, preparing for yet another tour, Presley was found dead at Graceland, officially of heart failure. There was much controversy about the cause of death, but what’s clear is that he died an opioid addict. It has long been reported that from January 1977 until his death, his doctor, the flashy George “Nick” Nichopoulos, had prescribed at least 8,805 pills and sundry forms of drugs that included Dilaudid, Quaalude, Percodan, Demerol and cocaine hydrochloride. (To reconstruct the prescription record, investigators had to contact 153 pharmacies in the aftermath of Presley’s death.) He was 42 years old.

V. THE AFTERLIFE

Presley’s death marked an odd new beginning. Tribute artists proliferated, and still do, filling venues with fans young and old. Admirers make their pilgrimages to Graceland. The truly devoted marry in chapels presided over by proto-Elvises in full costume, with the King’s music playing softly in the background. Why such a vibrant afterlife? There are Sinatra fans, but you don’t read about thousands beating a path to Hoboken or believing Ol’ Blue Eyes is really alive and well in Buenos Aires. (The latter was a persistent rumor in the wake of Presley’s death–that he had faked the whole thing and bought a ticket to South America under an alias.) “If you’re an Elvis fan, no explanation is necessary. If you’re not an Elvis fan, no explanation is possible,” Presley friend George Klein told Harrison, the British writer and broadcaster, who also authored the engaging 2016 book The Death and Resurrection of Elvis Presley.

The roots of that elusive explanation, however, may lie not in the mechanics of traditional celebrity but in the sociology of a force that was always vital in the lives of Presley’s most ardent fans: religion. In death, Presley has become a quasidivine figure whose savior-like appeal comes from his journey from the ordinary to the extraordinary. “It is very common for people to experience the divine in what can only be an inadequate human being,” Karen Armstrong, a scholar of world religions, told Harrison for his 1997 BBC documentary Elvis and the Presleytarians. “The essential and amazing thing about the spiritual quest is that the divine is able to be apprehended at all. So of course we think that Elvis is a grossly inadequate symbol of the divine, but one could have said the same of Jesus, after all. He died the death, the very common death, of a disgraced criminal.”

The trappings of the Presley legacy do echo religious ceremonies. His tribute artists–or priests, if you will–dress in white costumes, re-enact the actions and speak the words of the cultic founder, and make promises. In the Christian worldview, there is salvation, the forgiveness of sin; in the Presley ethos, there is freedom from restraint, affirmation. “His whole existence was to take guilt away from people,” the psychologist Richard Maddock told Harrison. “He started out that way and ended up that way. The first phase, on television in the 1950s, he did things that in those days people only did in private. It was like he was saying, O.K., you don’t have to feel guilty about it. In the second phase of his career, he added something. In his concerts, he not only did the movements and motions, by that time commonly accepted, but he also added spiritual songs at the end. In effect he was saying, Not only are your impulses O.K.–now they are blessed.”

Was Leonard Bernstein right? Did the whole ’60s come from Presley? Surely much of it did, and the ’70s too, and the ’80s, up to our own day. Presley’s life is a kind of American tragedy–a talent of epic proportions cut short by indulgence and appetite–but if his story is personally tragic, it’s a story that is not yet over. Shawn Klush, a Presley tribute artist who was on HBO’s Vinyl, will be at Graceland this month for the anniversary of the King’s death. “I believe Elvis remains so popular 40 years after his death mainly in part due to the kind of man he was,” Klush says. “People love him, not only for his talent, but because he was a great, humble, kind man. He loved God. He loved his parents. He loved his country.” And his country loved him–for his voice, for his spirit and because it saw in him, for better and for worse, what it was and what it hoped to be.

–With reporting by ANNA RUMER/WASHINGTON

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com