Adam Grant is an organizational psychologist, Wharton’s top-rated professor and a New York Times bestselling author who shares insights every month in GRANTED.

If you’ve read the recent memo by a Silicon Valley engineer about diversity, you probably had a strong emotional reaction.

It’s always precarious to make claims about how one half of the population differs from the other half — especially on something as complicated as technical skills and interests. But I think it’s a travesty when discussions about data devolve into name-calling and threats. As a social scientist, I prefer to look at the evidence.

The gold standard is a meta-analysis: a study of studies, correcting for biases in particular samples and measures. Here’s what meta-analyses tell us about gender differences:

1. When it comes to abilities, attitudes and actions, sex differences are few and small.

Across 128 domains of the mind and behavior, “78% of gender differences are small or close to zero.” A recent addition to that list is leadership, where men feel more confident but women are rated as more competent.

There are only a handful of areas with large sex differences: men are physically stronger and more physically aggressive, masturbate more and are more positive on casual sex. So you can make a case for having more men than women… if you’re fielding a sports team or collecting semen.

2. In the U.S., boys aren’t better at math than girls.

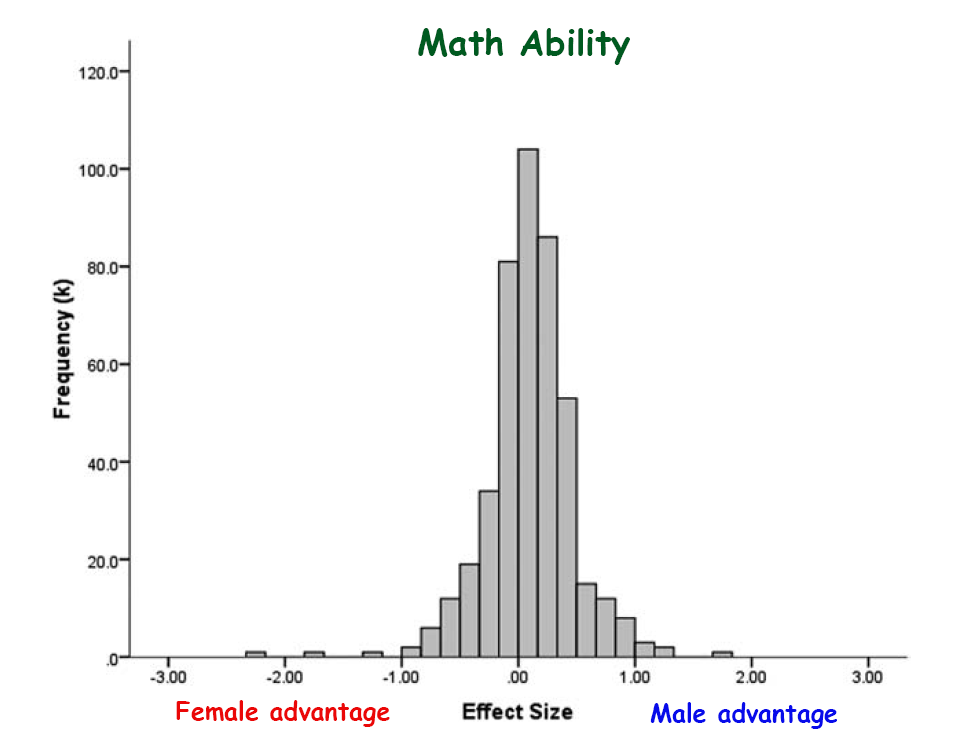

Across nearly 4,000 studies, the average gender gap in math achievement is not statistically different from zero. The two sexes have very similar variances, with men showing slightly more variability. And there are just as many cases where girls outperform boys in math as vice-versa:

3. Where male advantages in math ability exist, they’re heavily influenced by cultural biases.

Girls do as well as boys — or slightly better — in math in elementary, but boys have an edge by high school. Male advantages are more likely to exist in countries that lack gender equity in school enrollment, women in research jobs and women in parliament — and that have stereotypes associating science with males.

If you don’t see bias there, try this: when teachers know students’ names, boys do better on math tests. Yet when grading is anonymous, girls do better on math tests. And before a math test, reminding college students of their gender leads girls to perform 43% worse than boys. But if you just call it a problem-solving test, the gender gap in performance disappears.

Biases affect men, too. Women are stereotyped as more empathetic, and they do score higher than men when you test the ability to read other people’s thoughts and feelings. But if you don’t introduce it as an empathy test, the gender gap vanishes.

4. There are sex differences in interests, but they’re not biologically determined.

The data on occupational interests do reveal strong male preferences for working with things and strong female preferences for working with people. But they also reveal that men and women are equally interested in working with data.

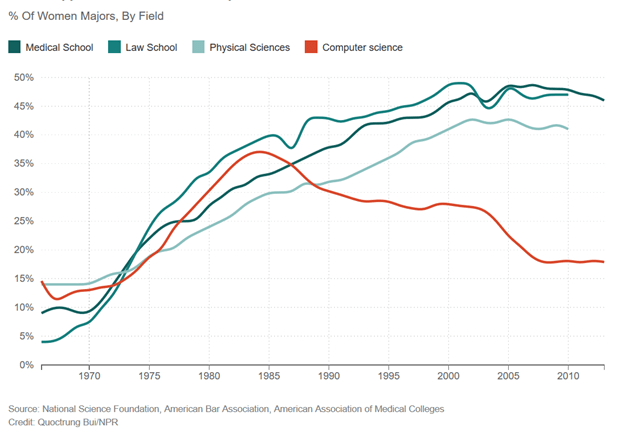

So why are there so many more male than female engineers? Because women have systematically been discouraged from working with computers. Look at trends in college majors: Since the 1980s, the proportion of female majors has gone up in science and medicine and law, but down in computer science.

We know that interests are highly malleable. Female students become significantly more interested in science careers after having a teacher who discusses the problem of underrepresentation. And at Harvey Mudd College, computer science majors were around 10% women a decade ago. Today they’re 55%.

It’s time to stop making mountains out of molehills. If men are from Mars, it looks like women are, too.

This article originally appeared on LinkedIn.com.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Breaking Down the 2024 Election Calendar

- How Nayib Bukele’s ‘Iron Fist’ Has Transformed El Salvador

- What if Ultra-Processed Foods Aren’t as Bad as You Think?

- How Ukraine Beat Russia in the Battle of the Black Sea

- Long COVID Looks Different in Kids

- How Project 2025 Would Jeopardize Americans’ Health

- What a $129 Frying Pan Says About America’s Eating Habits

- The 32 Most Anticipated Books of Fall 2024

Contact us at letters@time.com