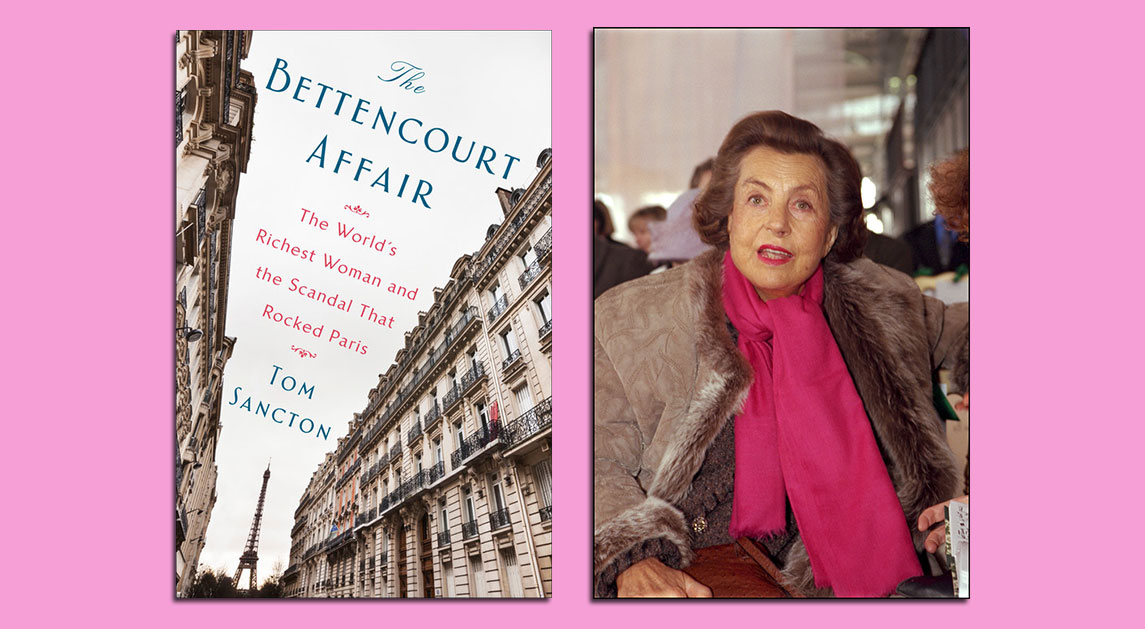

She is the world’s richest woman, worth $39.5 billion at last count, but no one could envy her. Liliane Bettencourt vegetates in an armchair in her Art Deco mansion near Paris, surrounded by her servants, dogs, and caregivers. She is deaf and lost in the fog of senility. Medical experts have diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease. One can only wonder what goes on in the old woman’s head. Does she harken back to her childhood as the daughter of Eugène Schueller, multibillionaire founder of the cosmetics giant L’Oréal? Does she call to mind her late husband, André Bettencourt, and his illustrious career as a government minister, deputy, and senator? Does she think of Françoise, her only child, the serious-minded intellectual who preferred her books and piano to the grand dinner parties and receptions given by her parents? Does Liliane even remember François-Marie Banier, the seductive photographer, artist, and writer who became her closest friend and, according to Françoise, sweet-talked her out of hundreds of millions of euros? And does she know that her daughter’s 2007 lawsuit against Banier triggered a judicial-financial-political earthquake whose aftershocks continue to reverberate?

It would be best for Liliane Bettencourt if she did forget that episode. For it poisoned her twilight years and exposed her private life, her extravagant finances, her free-spirited friendships, and her encroaching infirmities to relentless public scrutiny — which she denounced in her more lucid days as “the odious accusations that I read each morning.” That was in 2010, the year the Bettencourt Affair exploded onto the front pages and even threatened to engulf French president Nicolas Sarkozy in what the press referred to as a “French Watergate.” But long before it achieved such public notoriety, the conflict between mother and daughter and an audacious interloper was slowly brewing.

Perhaps it all started on a balmy July day in 1993. The scene was the Pointe de l’Arcouest, a promontory on the rocky, windswept northern coast of Brittany, where Eugène Schueller had built a grandiose vacation home in 1926. Liliane and her husband, André, loved to entertain there — presidents, ministers, movie actors, and famous writers had all enjoyed the Bettencourts’ hospitality over the years. But on this day, the luncheon was a more intimate affair. Seated around a granite table in the front dining room, whose large windows offered a panoramic view of the English Channel, André and Liliane were joined by their daughter, Françoise; her husband, Jean-Pierre Meyers; and their two young sons. Also at their table that day was a somewhat eccentric houseguest.

More from TIME

François-Marie Banier, then 46, seemed to know everybody who was anybody. His conversation was peppered with the names of celebrities with whom he claimed to have intimate friendships — Salvador Dalí, Vladimir Horowitz, Samuel Beckett, Isabelle Adjani, Johnny Depp, President François Mitterrand, and on and on. With his loud voice and explosive laugh, Banier was impossible to ignore. He was witty, cultivated, amusing, seductive. But he also had a gift for getting on people’s nerves. He often behaved like a child who was starved for attention — and he usually got it. Liliane Bettencourt, 70 years old and Banier’s elder by a quarter century, was clearly fascinated by him.

As seagulls circled and cried outside the open windows, Françoise, who had just turned 40, gazed at Banier through her heavy-framed glasses and watched her mother hang on his every word. Liliane, who suffered from progressive deafness since childhood, was all the more attentive in her effort to read Banier’s lips. All her life, Françoise had craved, but rarely received, the kind of attention that Liliane was lavishing on this invasive stranger. He spoke, Liliane laughed. He smiled, she melted. He bragged about his latest photo exhibition, she gushed praise for his work.

As for poor André, 74, a silver-haired senator and former cabinet minister, he had long since learned to put up with his wife’s whims and caprices. Liliane was the heiress, the one who held the purse strings, bought his elegant suits and cigars, and financed his political career. If Banier made his wife happy, André had nothing to say. Besides, he also found this gay artist amusing.

Jean-Pierre Meyers, 44, a bland-faced man with receding hair and arching eyebrows, observed the tense scene but said little. He was used to holding his tongue at these family gatherings. A practicing Jew, he well knew that the staunchly Catholic Bettencourts had not favored his marriage to Françoise, even though they brought him into the family firm. Someday, once his wife inherited the principal share of L’Oréal, he would be in a commanding position. Until then, he could afford to bide his time. But Banier’s presence doubtless made him uncomfortable. Between the two men there were not six degrees of separation but three: Meyers had formerly lived with the sister of Banier’s ex‑partner, actor Pascal Greggory. Meyers’s breakup with the woman had been followed almost immediately by his marriage to the future L’Oréal heiress. Excellent career move, but rather messy in human terms. Banier was a loose cannon, liable to bring up the awkward subject in the presence of Meyers’s wife, his children, and his in‑laws.

Banier did lash out that day — but Meyers was not his target. “He started speaking to my father with mocking, scornful and humiliating words,” Françoise later recalled. “Right in front of him and in front of our children! I found his behavior completely odious.” Françoise has never revealed the subject of Banier’s tirade, but another witness claims to remember the scene quite well. Serving at the table that day was Pascal Bonnefoy, André’s personal valet, a man so devoted to his employer that years later, after André’s death, he would shed tears at the mere mention of his name. According to Bonnefoy, “Banier addressed Monsieur with irony, almost aggressiveness. He reproached him for the articles he’d published during the war in a collaborationist [pro- German] newspaper. It was not a frontal attack but it was intended to wound. Monsieur was embarrassed. Madame didn’t react. At times like that, she knows how to play on her deafness. Only her daughter tried to intervene. The others had their noses in their plates. The luncheon was ruined.” (Banier remembers the scene quite differently, as an argument about musical preferences.)

The articles Bonnefoy referred to were anti-Semitic diatribes that André Bettencourt had written for a German-backed paper in 1941 and 1942, before he switched sides and belatedly joined the Resistance. Raising the subject on that occasion was doubly embarrassing, for Françoise’s husband was the grandson of a famous rabbi who had died at Auschwitz, and the couple were raising their two sons as Jews. Lurking in the background of all this was an even bigger family scandal: Eugène Schueller, the revered founder of L’Oréal, had financed notorious pro-Fascist movements and was investigated for Nazi collaboration after the war.

Following the luncheon incident, Françoise told her parents she no longer wished to be in Banier’s presence. But André and Liliane did not share her sentiments. The artist had been cultivating their friendship since 1987, and the Bettencourts, especially Liliane, welcomed his company. Flattered by Banier’s attentions, and delighted to be introduced into his glittering world of artistic and cultural connections, she began to lavish extravagant gifts on him. Gifts that, on paper at least, totaled nearly a billion euros at one point — a staggering amount even for one of the world’s wealthiest individuals.

But it was not just the money. As Françoise tells it, Banier so dominated Liliane’s time that she found it increasingly difficult even to see her mother — though she lives across the street from the Bettencourt mansion in the posh Paris suburb of Neuilly. It seemed, she said, as if Liliane had been “pulled into a sect” by a “guru who cut me off from my family.” Françoise looked on Banier as a sort of sibling rival, who attempted to insert himself into the family as a surrogate son and drive a wedge into the already troubled relationship between mother and daughter.

Things came to a head for Françoise shortly after André’s death in November 2007, when one of the Bettencourt employees gave her some stunning news: She claimed to have overheard a conversation in which Banier insisted that Liliane legally adopt him as her son. “That was too much,” Françoise recalled. “This man had denigrated my father, manipulated my mother, and shattered our family.” On December 19, 2007, she filed a criminal complaint against Banier for abus de faiblesse, or exploiting the weakness of her aged mother.

Thus began the nearly decade-long drama known as the Bettencourt Affair. Before it was over, an illustrious family was torn apart, careers and reputations were ruined, an army of lawyers made millions, an eminent barrister and a senior police detective committed suicide, a witness tried to hang himself, a tarnished president lost reelection, one of France’s proudest companies was threatened with a Swiss takeover, and François-Marie Banier, nearing the age of 70, faced the prospect of three years in prison and a ruinous fine. The greatest irony was that Françoise, who had launched the whole legal battle, found herself under investigation for allegedly bribing a witness.

The Bettencourt Affair is a modern-day Greek tragedy based on jealousy, greed, vengeance and retribution. It’s also a story about money: the creation from scratch of one of the world’s great fortunes, and the use and abuse of that fabulous wealth through three generations. The saga of the Bettencourt fortune has its dark chapters — the funding of pro-Fascist movements, the enormous profits made under Nazi occupation, a tide of secret political contributions, illegal Swiss bank accounts, and tax-evasion schemes. On the positive side, the family firm is one of France’s most dazzling industrial success stories, and the Bettencourt Schueller Foundation stands today as one of the country’s leading philanthropies, pouring hundreds of millions into medical research, the arts, education and housing.

For Liliane Bettencourt, the heiress who inherited it all, money has been the fundamental constant of her long existence. It paid for her mansions, her designer clothes, her travels, her army of domestic servants, even her own private island. Not least, it gave her the means to lavish gifts upon the charming artist who had opened the doors to a passionate life beyond the confines of the conventional bourgeois world into which she was born. And when her timid daughter finally rose up in protest, the Bettencourt billions were at the heart of one of history’s great succession battles.

Excerpted from The Bettencourt Affair by Tom Sancton. Copyright © 2017 by Tom Sancton. With permission of the publisher, Dutton. All rights reserved.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com