In 2015, as Russia plunged millions of dollars into an escalating disinformation campaign against the West, the European Union’s defense consisted of just one person.

A former journalist had been seconded from the Czech Republic to the E.U.’s newly-established East StratCom Task Force, and was working furiously to de-bunk the Kremlin-backed fake news that flooded people’s inboxes, TV screens, and social media timelines. “[He was working] literally seven days a week,” said an E.U. official involved in the bloc’s strategic communications efforts, who asked for anonymity in order to speak freely. “He was going to an early grave if we didn’t get some help.”

Getting help proved tricky. Despite a clear, and explicitly stated, aim from Moscow to use disinformation as part of its foreign policy, the E.U. moved at its customary slow pace. “Some countries didn’t really feel the threat,” said the official, citing the usual divisions which plague a co-ordinated E.U. response. While places like the Baltic nations, Poland, and Scandinavia—having been victims of Russian disinformation for years—advocated a robust response, others including Hungary and southern European nations which depend on Russian investment or energy were less enthusiastic.

Even Germany “wasn’t particularly supportive”, the official said: “They were not really convinced there was a problem.”

The U.S. elections apparently helped change their minds, with Moscow accused of deploying hacking and other means of disinformation to sway the result of the 2016 Presidential election. In September, it emerged that 3,300 Russia-backed ads had appeared on Facebook during the 2016 election campaign.

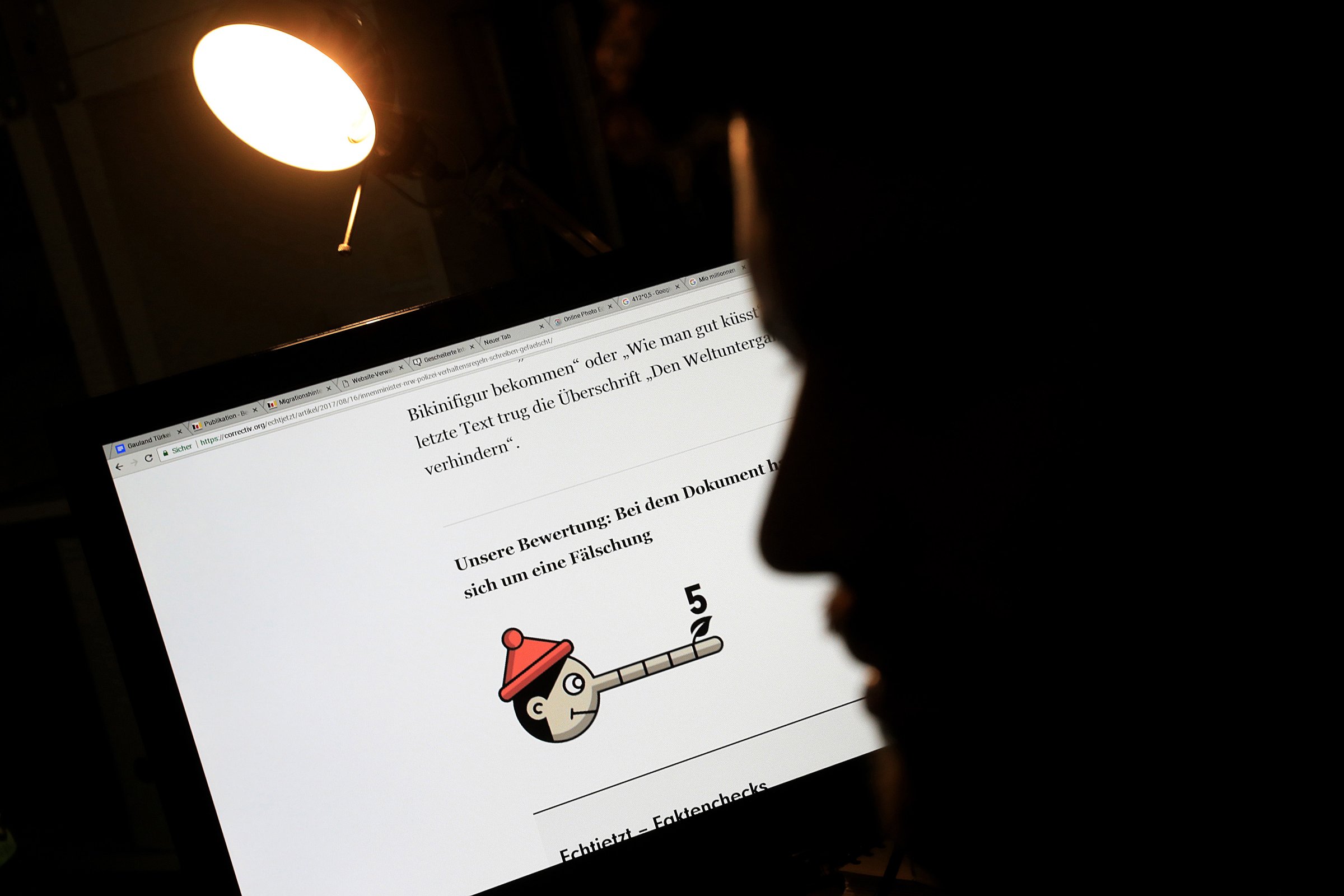

Now East StratCom is enjoying a reversal of fortune. On a recent visit to their headquarters in a bright and modern building in the heart of the E.U. district, staff were busy putting together their weekly newsletter. They have built a volunteer network of 500 NGOs, diplomats, think-tanks and other media professionals who regularly send them examples of fake news. These are then de-bunked in the newsletter, on Facebook and Twitter.

The efforts come as a string of high-profile European elections has raised awareness of Russia’s attempts to destabilize the democratic process. In the Netherlands, authorities reverted to counting ballots by hand to thwart any attempts at hacking in March elections. New French President Emmanuel Macron called Kremlin-funded media outlets RT and Sputnik “agents of influence” which spread rumours about him during the campaign. In Germany – which holds elections later this month — false reports on Russian media of a migrant raping a 13-year-old Russian-German girl brought thousands of people out into the street in protest, giving Berlin a wake-up call in the powers of propaganda.

But combating Russia’s propaganda networks remains a “David and Goliath struggle”, the E.U. official conceded. The Kremlin’s efforts to destabilize the E.U. and promote pro-Russian policy are alleged to include outright hacking, backing for anti-E.U. political parties, heavily biased news reporting, and an army of internet “trolls” who stalk social media with pro-Russian messages. East StratCom will have expanded to 14 employees by the end of this year, but only three of them are working full time on de-bunking disinformation. Their Twitter feed has around 27,000 followers — compared to 2.62 million for RT – while its Facebook page has just over 17,000 likes. Sputnik has over a million.

The E.U’s leadership says there’s only so much it can do, given the resources it is already pouring into multiples crises within Europe. Speaking to TIME in an interview in February, European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker said he was “certain that the Russians are trying by all the means they have to have a propaganda influence on European and international affairs.” But he added: “They have thousands of people telling stories which do not reflect reality. We have only a few people [rebutting these] because I don’t want to engage a thousand new civil servants to react.”

Maja Kocijančič, the spokesperson for E.U. foreign affairs, told TIME in July that East StratCom “is doing an excellent job operating within their current allocated resources”.

But for some, those “allocated resources” border on the negligent. In an open letter published in March, more than 120 signatories from across government, media, security and civil society accused the E.U. of being “irresponsibly weak” on disinformation. The European Parliament, meanwhile, called on the E.U. to more than double the staff of East StratCom and give it a budget in the millions.The 28 E.U. governments declined to back that proposal, and unit still does not have its own budget, relying on a small share of the E.U.’s existing strategic communications budget.

And the threat is far from over. As well as German elections on Sept.24, there are fears of Russian meddling in elections in Sweden in 2018, and in the European Parliament elections in 2019. “We are still reactive, not pro-active,” said Petras Auštrevičius, a Lithuanian Member of the European Parliament and one of the signatories of the open letter. Auštrevičius advocates more radical measures to curb the influence of Russian media. “I do not exclude a cut-off of the broadcasters,” he said. “If they are really hostile against us, against our values, we should not shy away from taking even more principled measures.”

He also thinks a proposed German law which would fine social media platforms up to $50 million if they fail to promptly remove “illegal content” should be expanded throughout the E.U. Earlier this year, the E.U. commissioner for the digital economy, Andrus Ansip, told the Financial Times that while he would prefer social media sites to pursue self-regulatory measures, they could be complemented by “some kind of clarifications”. He did not expand on what those might be, and replying to a question from TIME, his spokesperson once again stressed that “these media carry the main responsibility to act against fake news”.

So for now, East StatCom remains on the front line. A recent edition of the newsletter took on an implausible story published on Russian and Lithuanian news websites about an American B-52 plane dropping a nuclear bomb on a Lithuanian town. “If a tree falls in the forest and there’s nobody around to hear, does it make a sound?” it asks. “What about a nuclear bomb that falls over a Lithuanian town, and no one notices?”

But the question is — above the din of the Russian propaganda machine, can anyone hear the E.U.?

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com