Chelsea Carter grew up in rural West Virginia and began using prescription drugs when she was 12 years old. By her early twenties, she was stealing to support her addiction to the opioid OxyContin. She was eventually arrested and faced up to 20 years behind bars. But Chelsea didn’t go to prison; instead, she went to treatment court.

In this special court, Chelsea met regularly with a case manager, counselor and treatment provider. She appeared frequently before a judge who reviewed her progress, congratulated her on her successes and encouraged her when she needed it. Slowly, Chelsea began to turn her life around. With the help of the court, she enrolled in school and earned both her bachelor’s and master’s degrees. Chelsea would still be in prison today if it weren’t for drug court. Instead, she is a therapist at a treatment center in West Virginia. Every one of her clients has an addiction to opioids, and many of them are referred to her through treatment court programs.

There are more than 30,000 stories a year in America that begin like Chelsea’s but end with an overdose death.

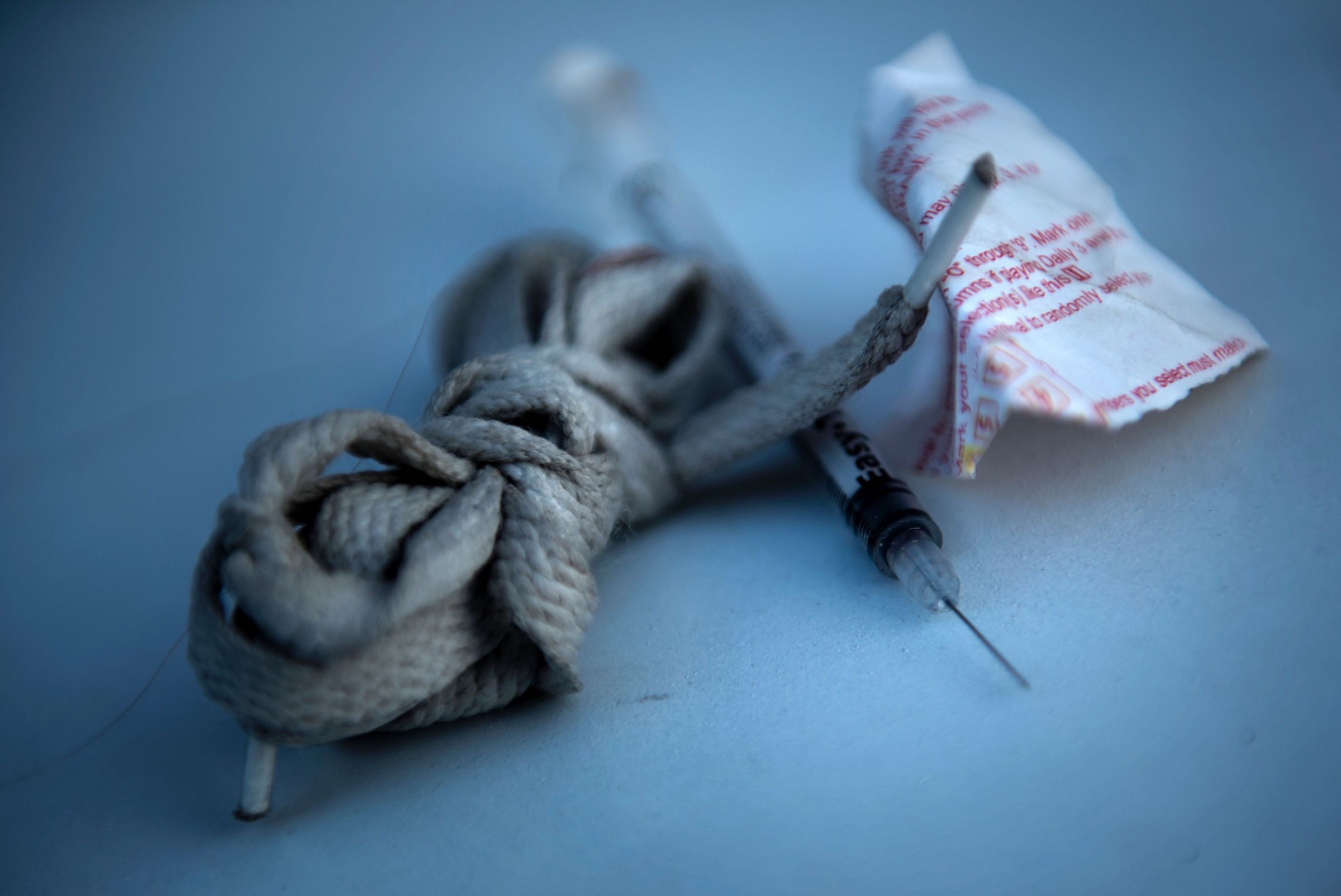

It is no secret that when it comes to politics, there is very little on which the two of us agree. But we both believe this: The opioid epidemic is now the greatest public health and public safety crisis facing this nation. It claims the lives of 91 Americans each day, tearing apart families and ravaging communities. As the war on drugs demonstrated, we cannot incarcerate our way out of this problem.

Rather than fill our prisons and jails with people who are addicted to drugs or who suffer from mental illness, Congress should look to proven solutions that promote accountability and treatment. One model that deserves more national attention is treatment courts, such as those for drugs and veterans’ treatment.

Drug courts emerged out of the cocaine epidemic of the 1980s. The idea was simple, yet profound: Instead of jailing people with serious drug problems only to watch them fall back into the throes of their addiction immediately upon release, drug courts are an alternative to incarceration that use the leverage of the courts to connect people with long-term treatment and supportive programming.

What started as an experiment has now become a successful method for helping people with serious substance use disorders get on a path to long-term recovery. In treatment courts, substance use and mental health disorders are seen as public health issues instead of moral failings. Participants receive evidence-based treatment — including medication-assisted treatment — and services to assist with education, employment, housing, family reunification and health care. Instead of a jail cell, they get accountability mixed with compassion and the opportunity to transform their lives. There are over 3,000 treatment courts in the United States, according to The National Association of Drug Court Professionals, and they help about 150,000 people go into addiction treatment each year.

Entrusting the criminal justice system with the difficult task of tackling a public health crisis seems counterintuitive. But it is already an unfortunate reality that the justice system serves as the front lines of the fight against addiction and mental illness. According to the National Research Council, more than half of the 2.2 million people behind bars in America suffer from at least one form of mental illness and often have concurrent substance abuse disorders. It is critical that courts be equipped with the tools needed to combat these crises — and most importantly keep people out of prisons and jails when treatment would be a far better option for individuals and society.

And if we agree that high-quality, affordable treatment should be available to every individual who needs it, we also must acknowledge that addiction leads some people to commit non–drug-related crimes that carry the potential of serious prison time. For these people, treatment court offers a life-saving alternative that holds them accountable for these crimes and provides treatment for their addiction disorder.

Treatment courts have been researched more than any almost any other intervention in the history of the justice system, with four studies just from the Government Accountability Office. The evidence is clear. These courts dramatically reduce recidivism, drug use and family conflict, while increasing education and employment. In fact, studies show that treatment courts reduce crime by up to 45% and save more than $6,000 for every individual they serve.

The emergence of medication-assisted treatment (MAT), which combines the use of FDA-approved medication with counseling and behavioral therapies to treat substance use disorders, has helped treatment courts become even more effective at treating opioid addiction. MAT helps many people leave a life of addiction — permanently. A person struggling with addiction is more likely to access MAT while in a treatment court than through standard probation or typical substance-use treatment.

This success has led to a variety of judicial programs that are now focused on treatment rather than incarceration for repeat Driving While Intoxicated offenders, parents whose children have been removed from the home due to substance use, juveniles facing criminal charges, tribal communities torn apart by addiction and veterans struggling with trauma. These programs prove that providing individualized treatment plans and dignity-restoring support is the most effective way to lead people into recovery and break the revolving door cycle of recidivism.

Treatment courts offer a stark reminder of the critical role the justice system can play in providing a public health response to addiction. Instead of putting people behind bars, treatment courts demonstrate that a combination of treatment and support can lead even the most seriously addicted people in our justice system to lives of recovery, stability and health.

Congress has traditionally provided federal funding to these court programs to assist implementation, expansion and the cost of treatment. The Department of Justice estimates that there are approximately 1.2 million people in the justice system who are eligible for treatment court but are unable to gain access. As lawmakers consider how best to respond to the opioid crisis, they should look to drug courts and other treatment courts as a proven solution in need of expansion.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com